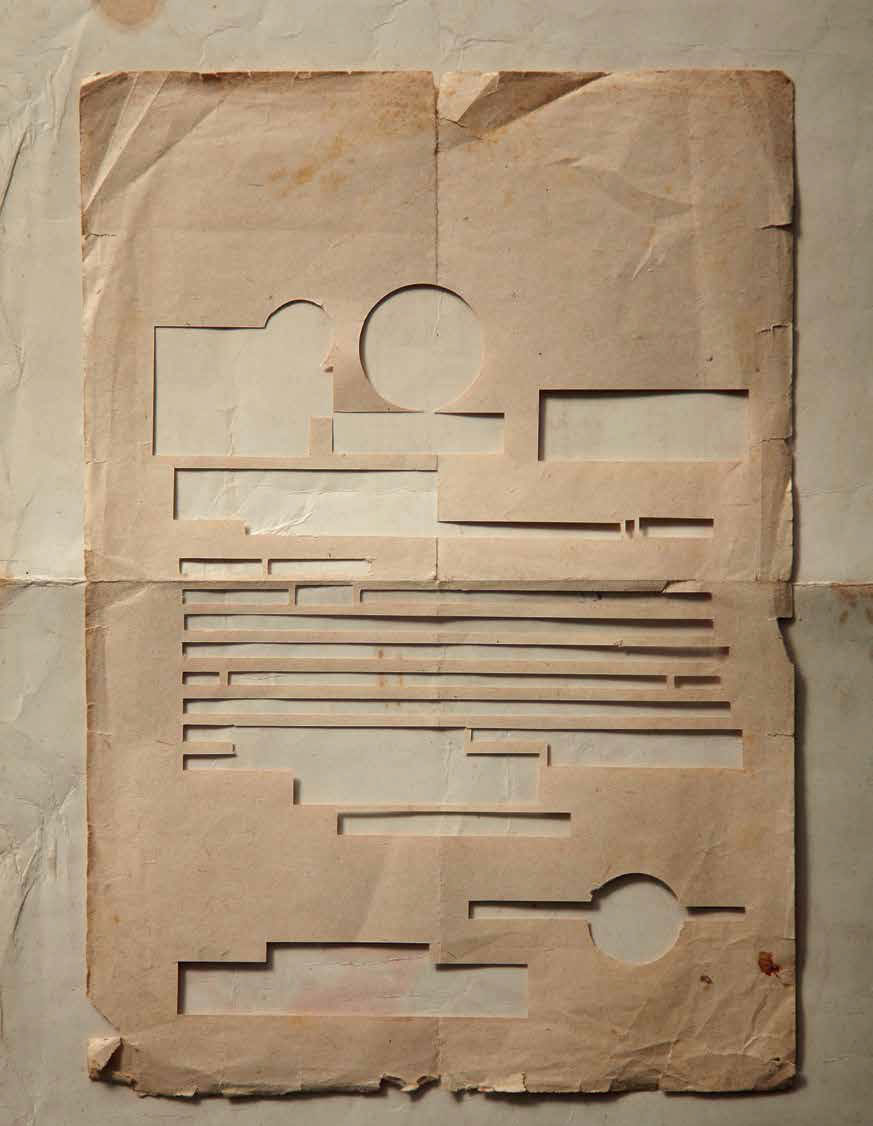

The written word will always be the most powerful weapon of all. Knowing this, there are those who need to silence it with guerrilla urgencies.

The written word will always be the most powerful weapon of all. Knowing this, there are those who need to silence it with guerrilla urgencies. When that happens, we can be sure that we are fighting for what is right. Only those whose silences are uncomfortable try to silence those who have an active voice. And that is why freedom of expression is the greatest flight of humanity.

Perhaps it is difficult to imagine, these days that we run around outside without apprehending much, days made of rush to go nowhere, what it would be like to be a student at the University Coimbra in 1961. The world was experiencing great upheavals. Winds of change were blowing from all over Europe. The same ones that would give rise to the May Movement in Paris and Spring from Prague, both in what was still the distant year of 1968. Hermeticism from Portugal, where the incoming information was carefully chosen by the censors, had some leakages via the emigrant community in France, which students from the former and always teeming academic republics had the capacity to interpret, in the light of the ideals absorbed from the prohibited literature to which they had access, taking great risks for this. One academic night, those where wine uplifts your mood and unlocks your tongue, two young men toasted, in such a loud voice as the glasses that clashed, “Cheers to freedom”. The details have been lost in time. It is not known whether there would be PIDE agents at the establishment, elements of the Portuguese Legion, any member of the vast network of informants or whether a mere exacerbated "aligned" citizen decided to make a call. The fact is, a few minutes later, the detention of these students, based on such a trivial that, fortunately makes this episode almost completely unlikely to happen today.

Inspired by these events, British lawyer and activist Peter Benenson writes an article that says: “Open your newspaper any day of the week and you will find a story of someone who was arrested, tortured or executed, anywhere in the world, for his unacceptable opinions or religion to the eyes of your country’s government. [...] The reader is left with a revolting feeling of helplessness. And yet, if these feelings of revolt around the world can come together in common action, something effective can be done.” The text, entitled The Forgotten Prisoners, called for the release of the two boys (what he calls “prisoners of conscience”), included an “Appeal for Amnesty 1961”. The weekend issue (Weekend Review) of The Observer newspaper publishes it. Other prominent newspapers from the most progressive nations in the world follow in his footsteps and that is how Amnesty International was born. The first meeting took place in July of that same year and already had delegates from the United Kingdom, Belgium, France, Germany, Switzerland, Ireland and the USA. After this, in an office too small for the huge library, Peter Benenson's chambers, located in Miter Court, London, adopts the Network of Three, a rule whereby each delegation will take care of three prisoners from different geographical areas, in order to attest to the organization's impartiality. Shortly after the first barbed wire candle is lit around it, which has become the symbol of the organization, in the London church of St-Martin-in-the-Fields, on Human Rights Day (10 December), the organization's first investigation mission is sent to Ghana. Czechoslovakia, the German Democratic Republic and, of course, Portugal (whose conditions under which arrests and horrible tortures of PIDE are included in the 1965 Prison Conditions in Portugal, one of the first reports compiled by the organization) followed suit. Ashamed of having, at times, justified such worthy interventions? We don't know half of the story. Because there are almost no people left who could tell us about it.

The freedom of Expression that we didn't have at the time of the Estado Novo was just the visible tip of a cold iceberg under which fear was. Silence was the watchword. From the outside, ideas considered subversive (just because they went against what were the national values established by Salazar) were forbidden by Censorship’s famous blue pencil. But we’ve spoken about it so many times that we tend to soften, in conscience, its impact. Sometimes, it’s necessary to particularize. Firstly, it should be noted that the Censorship Directorate was made up of officers from the Armed Forces, people without any sensitivity or cultural knowledge, who acted to “perform service.” It was up to the young nationals to "drink" from the great international phenomena (like the Beatles) and, under their influence, create what was the first great irreverence in Portugal, the National Rock. No, Rui Veloso is not the “Father of Portuguese Rock.” That is to ignore José Cid (who before going solo, even before being a member of the band Quarteto 111, already had Babies, a band of versions of Chuck Berry), Victor Gomes e os Gatos Negros, Joaquim Costa (the Elvis from Campolide) or José das Dores (Zeca do Rock). In the 1960s, the Monumental theatre started hosting Ye-Ye contests. Shortly after that start, we could read on a poster next to the main door, with the characteristics and design of the Estado Novo: “Youth can be cheerful without being irreverent.” It was not the lyrics of the songs that rattled the foundations of the regime. It was joy. The so-called “irreverence” that negatively influenced a youth that would be lost if, likewise, the songs of Zeca Afonso or Adriano Correia de Oliveira were not banned, the poems of Ary dos Santos at Festival da Canção and all the other cultural expressions that did not reach the most avid elite of modernism, but reached the heart of the people with melodies inspired by traditional music - and lyrics that shook the Estado Novo’s status quo. That was where the censorship service came in, at the service of the National Broadcaster, which, in addition to the prior examination of the news that aired, issued "internal service notes", written by the director of the program service or by the so-called musical and literary assistants: "inappropriate and inconvenient for transmission", "must be removed from programming" or "by superior determination, it cannot be transmitted" were some notes of the notes taken at the time.

In literature this “monster” took on even more frightening contours. In 1939, Miguel Torga was arrested when he published Fourth Day of the Creation of the World, an autobiographical novel describing the Franco regime. Many others followed. Until the brilliant Portuguese writers created Neo-Realism, a genre that allowed them to portray, from the perspective of the poorest (the overwhelming majority of Portuguese), the decrepit state in which Portugal found itself, poetizing it or using metaphors so creative that the establishment, in the 1950s, of a Reading Council, designed to guide the procedure of Army officers, wasn’t able to stop future “subversive” editions. The greatest example of their complete lack of knowledge about their work is perhaps the novel Esteiros, by Soeiro Pereira Gomes, a dramatic portrait of the living conditions of a group of boys forced to work in a brick factory, on the banks of the Tagus river, in Alhandra. It was published in 1941, with illustrations by Álvaro Cunhal. But only in 1966, when Europe-America Publications launched its 5th Edition, was this novel “noticed” by the very competent services, by dispatch 7801, where we could read: “It portrays the problem of floods in the Tagus River and the tragic consequences for the referred populations, in all aspects, it seems to me that for other speculative purposes, it gives rise to a great tragedy with loss of life, which does not seem to me to correspond to the truth (...) I believe that this book should have been forbidden when it was published (25 years earlier) but now it must be ignored, since the ban now, would only serve its propaganda in our midst, that could ignore it.” It should be noted that this dignified censor wrote “forbidden”, if we can draw the obvious conclusions from it.

“Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression, which implies the right not to be disturbed by their opinions and to seek, receive and disseminate, regardless of borders, information and ideas by any means of expression”, is a quote from Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As it appears in this document, Freedom of Expression is enshrined in almost every Constitution of modern democracies. But the reality is a little different. Prisons continue to exist for different opinions. For requesting, receiving, sharing or disseminating information or ideas different from the instituted powers. In many of the cases in which this happens, being able to do so is crucial for education, for the personal growth of individuals and, subsequently, to help the community where it operates, so that it can access justice and, therefore, be able to enjoy all other rights which, when there is not even freedom of expression, are certainly forbidden. Fear is the first outcome. And the first battle won by the oppressor. Where there is fear, there is a loss of combative spirit. And once this one is dead, the road is open for all kinds of abuse. Journalists are an essential pillar in a so-called fair society. They point out, imbued with impartiality, issues that are of interest to the society they are a part of. They are the ones that enable another universal right, that of access to reliable and exempt information. However, they are often persecuted for revealing facts that “pinch” the instituted power. Repressions and attacks happen a lot in some parts of the world. This can range from cases as simple as that of Suchanee Cloitre - the Thai journalist sentenced to two years in prison for defamatory acts, due to a comment on Twitter about a complaint of mistreatment filed by 14 Burmese immigrants to the aviary company Thammakaset where they all worked - to Syria, where journalists who reported human rights violations were arrested, tortured and killed. How did you find out about this? By fellow journalists whose goal is to show the world what they suffer locally. In these cases, freedom of expression acquires much broader outlines. It can save thousands of lives.

The “problem” starts right away in Ancient Greece. This is where the first concepts of what is a democratic society today are born, such as justice, freedom and, of course, democracy. Democracy that has an etymological problem... Only those who were part of a Demos (Municipality) could participate in politics. They met at the Ágora (public square) to deliberate on what, eventually, would be in everyone's interest, expressing their ideas freely. But women, slaves, prisoners and foreigners had no right to participate in politics. Freedom of expression, the key to the pursuit of life in Athens (there was no difference between State and Society) was thus forbidden to the overwhelming majority. It is Aristotle's claim that slaves should perform all kinds of manual labor so that citizens could have all their time available to participate in political activities. Today, there are other established freedoms that lend greater breadth to the concept of Freedom of Expression. Even so, it would be interesting to look at the possibility of modern times being, on one hand, limiting freedom of expression and, on the other, diametrically opposed, using that same freedom of expression to instill ideals that deprive us of so many other freedoms.

Social networks and, specifically, Facebook, for example... We all know friends who, at a some point, were “censored”, that is, “forbidden” from posting, commenting or even accessing their account for a certain period of time. It was not, in fact, Facebook and its algorithm. Algorithm "hides" photos of a violent nature and, above all, nudity. Or the concept of Facebook nudity, which involves allowing booty pictures but banning nipples. It's complicated. What actually happens is that another user or a group of users “reports” the publication for finding it “offensive”, according to what is their opinion. Which is valid if it doesn't endanger the next. Facebook's “censors” analyze this request and a message is sent claiming that the “Community Standards” have been violated. In other words, for this to happen, it is enough for someone to have been offended in their beliefs or ideals, to have been particularly attacked by a generalization, or simply someone who is “not cool with” a user for him to be immediately deprived of their Freedom of Expression which, we thought, was an inalienable right. But it is a resource that has proved to be very useful regarding the following situation. There is, at the moment, a party with parliamentary representation that, before having it, made it clear that its ideals were unconstitutional and many of its ideas went against everything that was conquered by the still impoverished Portuguese democracy. Even before the elections, it published a Political Program on his website where serious attacks on individual freedoms could be pointed out and, whether we like it or not, the egalitarian ideals on which both our democracy and the most basic human rights are founded. All this having escaped the highest levels that decide to be a “viable” party or not, the elections dictated that that party participate, today, in the discussions of the hemicycle. However, at least an interesting phenomenon is observed. The xenophobic dialog, based on extreme right-wing ideals, suddenly became appropriate, mainly on social networks. Because the defense argument is about the call for Freedom of Expression. Facebook is flooded with “support” pages, which publish fake news and incite hatred against immigrant communities, which in turn are flooded with false profiles that attack, often excessively and even violently, those who criticize the (at the very least deplorable) political positions, prejudiced considerations and silly statements by its sole deputy. These actions target everything and everyone, from publications by the media to mere publications by comedians or personalities with some weight in Portuguese society. When these people are less "opinionmakers", they even get their profiles deleted by Facebook. It is the suppression of the most basic rights using the supposed defense of a fundamental right, which is Freedom of Expression. And that inevitably relaunches the discussion of its limits. Are there? Yes. That’s how we understand how Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro were elected. Weigh the dangers that this represents or the obvious consequences for our fragile society. And conclude that, for now, there must be Freedom of Expression in a democratic society unless the expressions used with the freedom of expression that assists them endanger democratic values. And Freedom itself.

This article was originally published in Vogue Portugal's Freedom issue, from April 2020. Para ler este artigo em português, veja a edição de Liberdade da Vogue Portugal.

Most popular

.jpg)

Relacionados

.jpg)

Anna Wintour e o presidente da câmara de Milão, Giuseppe Sala, revelam a localização do Vogue World 2026

24 Feb 2026

O que lhe reservam os astros para a semana de 24 de fevereiro a 2 de março

24 Feb 2026