“Angola ’74” or “Amor de mãe”. Tattoos got a bad rep and it wasn't (just) because of the bad taste of some in their choice of design. It was because of our social constraints, because of their underground nature, because they didn't fit in with the norms. But when we get rid of prejudices, we realize that Beauty is not just bare skin: it is also tattooed.

“Angola ’74” or “Amor de mãe”. Tattoos got a bad rep and it wasn't (just) because of the bad taste of some in their choice of design. It was because of our social constraints, because of their underground nature, because they didn't fit in with the norms. But when we get rid of prejudices, we realize that Beauty is not just bare skin: it is also tattooed.

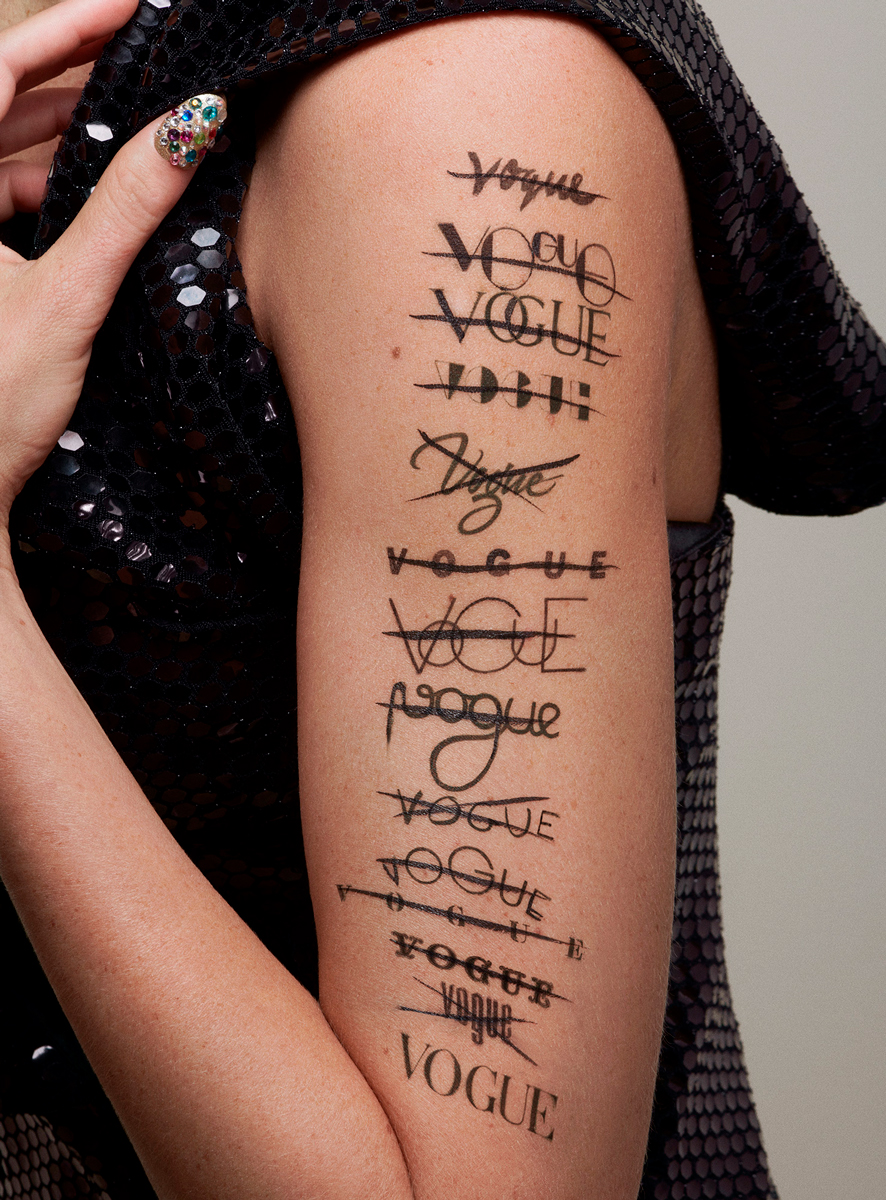

© Jamie Nelson

© Jamie Nelson

And it also has a history linked to the female gender. Although the oldest mummy discovered with tattoos is a man (Ötzi, the Iceman, was found in the snow of the Alps in 1991 and dates back to about 5,300 years), the next earliest post-Iceman discoveries were of Egyptian mummies over 3,000 years old, all of them women. What does it mean? First of all, that talking about the underground movements that started in the 20th century seems like child's play when compared to the history of tattoos, one with ancient records – did you know that there are bronze utensils identified as tools for tattooing, dating back to 1450 BC? But it would also be wrong to catalog it as underground since its origins, because the practice of tattooing the body was not only normal, but also therapeutic. The corroboration of tattoos on women in Ancient Egypt is linked not only to the representations and illustrations of the time (which showed the female figure with drawings on the buttocks), but also in the discovery of fmale mummies, not only Egyptian but also Greco-Roman, who exhibited this type of body art. Because it seemed to be an exclusively female practice in antiquity, many female mummies discovered with tattoos were despised by Y-chromosomed archaeologists (if tattooing was counterculture, a woman with tattoos was even more so), as they were identified as personalities of dubious status, an acceptance that could not be further from the truth: these mummified women would have been buried, elucidated Joann Fletcher, a researcher at the University of York, UK, in an interview with Smithsonian magazine, in 2007, in an area associated with elite and royal funerals and one of them has been identified as Amunet, a hierarchically well-positioned priestess. Some beliefs pointed to the location of these tattoos as a sign of prostitution, but time came to determine a new argument: these tattoos had a medicinal role and worked, for example, as a powerful amulet during pregnancy and childbirth. The theory is supported by the distribution of patterns around the abdomen, on top of the buttocks and chest, and by the type of design: the distribution of dots that would later expand as the belly grows was reminiscent of bead strands discovered in mummies intended for protection and safeguarding; also, there was the illustration of deities such as Bes (protector of the house, women, motherhood) on top of the buttocks. The researcher added that tattoos, even if unconfirmed, should have been done by older women to younger women, in a ritual that seems to have been, at the time and in this context, an exclusively female practice. The therapeutic side also gained corroboration in Ötzi, who had tattooed lines on his spine and knee and ankle joints, key points for acupuncture, and which later X-rays revealed that the man did indeed suffer from arthritis. But tattoos, and this should not come as a surprise, worked and also work, in many cultures, as a sign of identity, of belonging, of status – even in Egypt, later on, male leaders from neighboring Libya were represented with tattoos; in Greece, the writer Herodotus confirmed the existence of the practice of tattoos, pointing to them as “a mark of nobility and, not having them, is a testimony of a low birth”; and there are records of Britons whose tattoos were a way of showing the importance of their status. There is further evidence to suggest that the Mayans, Incas and Aztecs used the practice of tattooing in rituals; and that the Nordic people permanently inked the family crests on their bodies.

Of course, Humanity likes to pervert the course of History and nothing happens in a linear way over time. The passing of centuries – and the practices and evolution of societies – brought a new social look to tattooing, starting with the fact that the Romans and Greeks used it as a way of “marking” slaves and criminals, in a kind of punishment (the Japanese had similar practices) – even if, contemporarily at the time, Roman rulers and soldiers wore them with pride. The stigma, therefore, did not stick in a vehement way… at least until the arrival of Christianity, which saw in tattooing a way of “disfiguring what was made in the image of God”. Tattoos were therefore banned by Emperor Constantine. From then on, the practice that identified itself as cultural became a subculture, creating roots for a prejudice that still persists today, more or less depending on where you move around. “I think there is a whole historical context for an analysis of this kind”, begins Nicole Lourinho, tattoo artist at Arca Tattoo Parlour, in Lisbon, when we talk about the dissipation (or not) of stigma nowadays. “Even because we are analyzing what is recent history that links tattoos to the most marginal environment, in the West. But the panorama of tattoos is millenary. And it is assumed that, at that time, they were linked to hierarchical contexts, ritual situations, achievements within the tribes, etc; from the moment the expansion of Europe to the rest of the world takes place, we became aware of these types of practices (these meetings resulted in the collection of details in diaries with illustrations, which arrived to our time). What happens afterwards is what happens, as a rule, in the history of conquests: the practices of the subjugated people end up being smothered by the dominant culture, in this case, the Western or European. This means that, despite persisting in time elsewhere, it was seen in Europe as a counterculture, because it was part of the colonized tribes and not the social rules of the Old Continent. In fact, there are still tattoos made using the techniques from that time, which are centuries old. With bones, fish bones, for example. In more recent history, this has more to do with the groups they have become associated with. There is a generalization of those who used the tattoo that ends up reaching our days. And even though we're moving further away from that stereotype, that doesn't mean it doesn't keep happening.” We don't need a sociologist to know that these conditions that have persisted for centuries are instilled in us in such a way that they aren't even optional, but rather tattoos of discrimination in our social DNA (pun intended). This is perhaps why we tend to see tattooing - this permanent process (with almost zero possibility of removal) made on human skin through the subcutaneous introduction of pigments through needles - as an underground practice and not as socially normalized, a vision later underlined by the counterculture movements that emerged and that were alien to it, but that adopted it. The truth is that the currents of protest, when they arise, also tend to seek practices from other people that go against the norm of society, so it is normal that, in a westernized society that does not adopt the practices of the colonies, it's exactly those that subculture groups go after. It is clear that the panorama, namely in more developed societies and with the advent of information dissemination, has changed, although this change is slow and still has some way to go: “stigma has changed, but it doesn't happen in a day”, emphasizes Lourinho. “Tattoo has been appearing, progressively, in a more democratized way, in the media, in renowned names such as football players and actors who are tattooed, but also in reality shows, on social media… there is a kind of normalization. This doesn't mean that there aren't those who have different and unfounded opinions, as in all situations of discrimination. Also because it is something that draws attention and manages to be unusual, in certain contexts: a person who is fully tattooed still gathers some stink eye, for example. But less than it would have a few years ago. The way I feel like a minority on the beach changes completely when I'm at Arca [Tattoo Parlour].” In fact, a 2017 study carried out by the University of Northern Iowa, the BBC writes in a 2020 article on tattoos in the workplace, revealed that, in two different age groups (19 years old versus 42), both labeled people with tattoos as less favorable in terms of honesty, success, trust and intelligence (which is surprising, as one would expect the younger, more open and informed – and tattooed – layers to reveal a different perception). The only exception was in tattooed women, perceived as “strong and independent”, says the article.

Nicole Lourinho should be one of them. She “wears her tattooed heart on her sleeve”, or better yet, all over her body, displaying tattoos on both her legs and arms – and also feels discrimination skin-deepn. But she realizes she has fewer looks today than she would have 100, 50 or even ten years ago. And she also understands that, often, as in everything else, she endures the misinformation and our own social prejudices, the result of our environment upbringing and learning. Knowing a little more about tattooing is knowing that having tattoos is using a small fortune on your body, because it's not a cheap practice – at least, not if it's done with reputable professionals. “A tattoo always starts with a minimum price, which is related to the opening of material for a tattoo – the machine, inks, gloves, hygiene material –, regardless of the size of the tattoo”, she explains. “I can't put forward any reference value because different stores charge different prices, but it usually starts at several tens of euros and can go up to hundreds and even thousands, depending on the size, design, number of sessions, etc. Also because it has many variants: if it's a custom work, the details, the time needed… like a work of art. Even because there are people looking for the style of a specific tattoo artist (each tattoo artist ends up working their own trait) and this is also valued”. But it is not (just) because you pay for talent that it's costly: there are a series of costs that a tattoo shop has to have to ensure not only the comfort of the client and the tattoo artist, but also safety and health: “we, at Arca [Tattoo Parlour], we sterilize all the material that is reused, and everything that is not sterilized is because it is disposable. It has always been like this and it is not a post-Covid measure”, explains the tattoo artist. “It's one of the buzzwords of good practices, which you get to know right away when you're in the learning phase: don't take chances with people's health. The trustworthy tattoo shops, the ones I know, have always put safety, health and hygiene of clients and artists first. It also seems to me that it's common sense, some of these rules, of course. It seems basic to me to know that you can't share tools. It was unfair during Covid-19 that we were prevented from exercising when our practices always went beyond the post-pandemic safety restrictions imposed. We were already doing all of that – and more.” Another trait in tattooing is related to the morphology of the skin and respect for other professionals, namely, health professionals. For example, “one of the things a good tattoo artist pays attention to is to tattoo around and never over signs, as they may need to be monitored. My drawings are placed so that they remain visible so as not to interfere with later medical work. We also have other issues that we pay attention to, relating to people's faculty – we don't tattoo those who appear drunk, minors, etc."

Even in the way it's approached, it's a business like any other in terms of professionalism and basic hygiene and safety measures. Does this mean it's all about quality? No, as in any industry, there are the best and the worst: “choosing a good tattoo artist means doing your homework – being in a shop can be a good indicator, as a rule it is a trustworthy sign”. Lourinho reveals. “The best thing is to see work done already, work that's healed, etc. It's like everything else: you go through training and you evolve. But in tattooing there is not much notion of the professional path, so there are more doubts. When choosing a tattoo artist, word-of-mouth is still the best way to check quality. People will always talk and praise and the artist gains credit. And word-of-mouth also applies to studios, of course.” The fact that there are bad professionals gives tattoo a bad name, but it also confirms that it is a section of the market like another one for goods and services, because everywhere there are people who give the business a bad name. But that's not why it's underground – the stigma comes from our social stigma, which good professionals have been changing. Also because the work of those who are good has a window to the world, in walking 'ads' that appear on everything that is a consumable platform, from social networks to television, and this has helped to place them on the side of acceptance more than of denial: “I think tattooing can already be considered mainstream, from the moment you even have reality shows about it. It complies with what society already considers more normal” – let's pause to mention that even Justin Trudeau, Canada's Prime Minister, has a tattoo. “But it will continue to have an underground component. Because there is still tattooing raised to a level that is not accepted”. Truth: in the same study listed by the BBC, it was mentioned that even those who have tattoos can see them in others with a negative connotation, because they tend to internalize stigma and believe in it. For example, in companies with a strong component of prejudice against tattoos, it is possible to be a tattooed CEO and avoid hiring tattooed people, especially if you work in more corporate environments, such as banking. In Japan, there is the idea of a strong link between tattoos and the yakuza, gang members who displayed designs as a sign of wealth, virility and the ability to withstand pain, which made tattoos illegal in that country until 1948. But the opposite has also happened. In 2019, the airline Air New Zealand abolished its rule that prevented employees from having visible tattoos because it meant that traditional Maori matkings, with a strong cultural component, would have to be covered, creating a backlash against the company. Nicole argues that what's important is not to have tattoos or not, it's the beauty of acceptance of everything: “the funny thing is there's space for those who have an ankle tattoo, for those who don't have any, for those who only have one on their arms or on the legs and for those who are tattooed from head to toe. What matters is having respect”.

Still think tattoos are underground? At this point, even I start to question whether this article belongs in this theme, because tattoo is more about culture than counterculture, and more about art than activism, if we really think about its genesis, its tradition, what it really means and not the meaning that societies throughout history wanted to impose on it. Because tattooing the body is not, at its core, an act of rebellion, but an act of identity and love. For what one is, for the Beauty of a gorgeous design, and yes, maybe just activist enough so that one can inscribe in the body, even in abstract lines, even if subliminally: I love myself. At least, that's what in theory – and in practice – this art of tattooing is intended to be.

Originally translated from Vogue Portugal's Underground issue, published October 2021.Full credits on the print issue.

Most popular

.jpg)

Relacionados

.jpg)

Anna Wintour e o presidente da câmara de Milão, Giuseppe Sala, revelam a localização do Vogue World 2026

24 Feb 2026

O que lhe reservam os astros para a semana de 24 de fevereiro a 2 de março

24 Feb 2026