David Lynch meditates. Marina Abramovic too. Salvador Dalí, on the other hand, preferred his nap time – with surrealistic outlines, of course. Others opted for paths not as orthodox. Fernando Pessoa had a soft spot for opium, Baudelaire was faithful to alcohol. But some prefer simpler tricks, like the good old last-minute panic. We’re not the ones saying it, Truman Capote does.

David Lynch meditates. Marina Abramovic too. Salvador Dalí, on the other hand, preferred his nap time – with surrealistic outlines, of course. Others opted for paths not as orthodox. Fernando Pessoa had a soft spot for opium, Baudelaire was faithful to alcohol. But some prefer simpler tricks, like the good old last-minute panic. We’re not the ones saying it, Truman Capote does.

“I feel like I’ve never lived a single moment of peace, apart from the occasional calmness that a Nembutal induces. […] But I must say that a little bit of stress, the struggle of meeting a deadline, is good for me.” A confession by the author of, among others, Breakfast At Tiffany’s (1958) and In Cold Blood (1966) to the magazine Paris Review, in 1957. In an interview about the “art of fiction”, Capote (1924-1984) revealed to still be a “horizontal writer”. What does this mean? “I can’t think unless I’m laying down, whether in my bed or stretched on the couch with a cigarette and a cup of coffee in my hands. I have to be smoking and drinking. As the afternoon rolls over, I switch from coffee to mint tea, and from sherry to martinis. And no, I don’t use a typewriter.” The conversation also managed to reveal a few of his superstitions – which apparently have nothing to do with habits, or techniques, to induce creativity but, as you’ll see, it doesn’t verify – which included, for example, never start or finish a book (“anything”, in his own words) on a Friday. Hence why this text was concluded on a Sunday, we wouldn’t want to jinx it.

Who also had a few unhealthy habits, at least according to his time’s paradigm, was James Joyce (1882-1941), the man behind classics like A Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Man (1916)or Ulysses (1922). Although he followed a religious regime, that allowed him to “fall into line”, he once described himself as “a man of very few virtues, prone to extravagance and to alcoholism.” According to his biography, compiled by Richard Ellman, before creating, Joyce needed to suffer – or at least, to access a state of numbness: “Nora [his wife] brought him coffee and buns to bed and he lay, as Eileen [his sister] described it, ‘suffocated by his own thoughts’ until close to 11 o’clock.” Something that would be unthinkable for Georgia O’Keefe (1887-1986), one of the most important painters of the XX century. She who is, to this day, considered the “mother of American modernism”, used to wake up early, very early, which allowed her to watch the sunrise. After this, she’d start working immediately, quietly and without interruptions. According to her, “the morning is the best time, there’s no one around.” People, and noise, are things that ceased to exist inside the car of Vladimir Nabokov (1899-1977). During a trip in the United States, it was on the back seat of his car that we started the first draft of Lolita (1955) since that was the only place “without noise nor air drafts.”

Indifferent to the buzzing, Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008), one of the biggest names in abstract expressionism, had distinct habits of his own. He would start the day with a proper breakfast, took his vitamins, and had an express – double or triple. However, the center of it all was television, which was on, in the background, playing soap operas, namely The Young and the Restless, which premiered in 1973. David White, the senior curator at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, told the website Artsy, in 2016, that it was a source of “visual stimulation”, since the artist was an avid consumer of images, from newspaper and magazine clippings to glossy magazine’s photographs. Andy Warhol (1928-1987), also an admirer of anything “popular” and glossy pages, wouldn’t leave the house without speaking on the phone to his friend, and secretary, Pat Hackett, a call that would resume the events of the day before. Only two hours after that “moment”, which began to happen in 1976 and only ended with Warhol’s death, would the painter take a shower and get dressed. The rest of his mornings were spent out shopping, usually in Madison Avenue – only then would he make his way to the Factory, where the magic happened. It’s what we’d call mundane pleasures. There’s one for everyone. Some are more dangerous than others. But they’re all valid, nonetheless.

Yves Saint Laurent (1936-2008), one of the biggest geniuses in the History of Fashion, lived between Paris and Morocco where, allegedly, the unhinged consumerism of narcotic drugs fed into his creativity. Coincidence or not, his most memorable collections were conceived while he was on his Marrakesh safe haven, with the more-than-likely help of a drugs and pills cocktail. Yves is far from being a unique case. It is known that Fernando Pessoa (1888-1935), like other artists of his time, used to go to cafes and clubs to talk, exchange ideas and escape the monotony of daily life. It was then that, oftentimes, he succumbed to the delight of opium. Álvaro de Campos, one of his most important heteronyms, dedicated a poem to it, Opiário, where one could read: “It is through opium that my soul is sick / To feel life tires and rots / And I turn to the opium that comforts / An Orient to the orient of Orient.” Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) one of the most prominent English authors, didn’t run away from the topic and portrayed, in The Doors Of Perception (1954), his experiences with hallucinogenics, underlying the importance these had in the search for a certain evasion of normality: “Most men and women have lives that are, worst-case scenario, painful, and, in the best-case scenario, so monotone, poor and limited, that the need to escape, the craving to transcend themselves, even if just for a moment, is, and always will be, one of the main appetites for the soul.” Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), poet, essayist, and responsible for the masterpiece Les Fleurs Du Mal, published for the first time in 1857, was not modest when it came to acknowledging where his inspiration started and ended: “You need to be drunk all the time.” Like him, also Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), Amadeo Modigliani (1884-1920), F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940), and so many others, succumbed to this dependence, where almost all of them “traded the day by the night” and, almost all of them, became “addicted” to that extra cup to reach a state of bliss. Were they, because of that, less brilliant? No. Never. Health issues aside – because they matter, and many of them left us too soon because of them – it is almost irrelevant to know how Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961), him also a loyal friend to alcohol, managed to have the ability, the dexterity, to write powerhouses such as The Sun Also Rises (1926) or A Farewell To Arms (1929). His work was simply astonishing. Period. But, for the sake of the curious among us, let be added that he would do so standing up, wearing his oversize loafers, surrounded by junk and a painting where he noted the number of words he would write every 24 hours.

“For a poet is a light and winged thing, and holy, and never able to compose until he has become inspired, and is beside himself, and reason is no longer in him.” The quote belongs to Plato (427 B.C. – 347 B.C.) and it seems to indicate that, in order to create, an artist must reach a state that goes beyond simple reasoning, usually incompatible with the mundane habits of an ordinary person. Hence, it is not weird to realize how that thing we call “searching for inspiration” is as old as mankind itself. In Ancient Greece, creativity would come, almost always, from the divine. Luís de Camões (1524-1580) also called on his nymphs, dedicating sonnets to them. Each individual finds a way, or a style, that allows them to produce, invent, imagine. They can be actions as prosaic as taking a walk, sleeping, or even meditating – Marina Abramovic believes in the power of meditation so, that she developed her own method, named precisely The Abramovic Method. Others follow different paths. “Every morning, as I wake up, I experience ultimate pleasure: being Salvador Dalí, and I ask myself, amazed, what prodigious thing he’ll do today, that Salvador Dalí.” The confession was written by the Spanish painter in 1953. Dalí (1904-1989), known for his eccentricities, kept the ritual of taking a daily nap, which he called “key-locked sleep”. The ceremony included turning a plate upside down, on the floor, under his lounge chair, and holding a heavy key between his fingers. When he’d begin to fall asleep, the key would fall from his hand, eventually landing on the plate, with a noise that would wake him up. The creative ideas that resurfaced in between those moments of light sleep and awakening wielded, afterward, considerable influence over his surrealistic style.

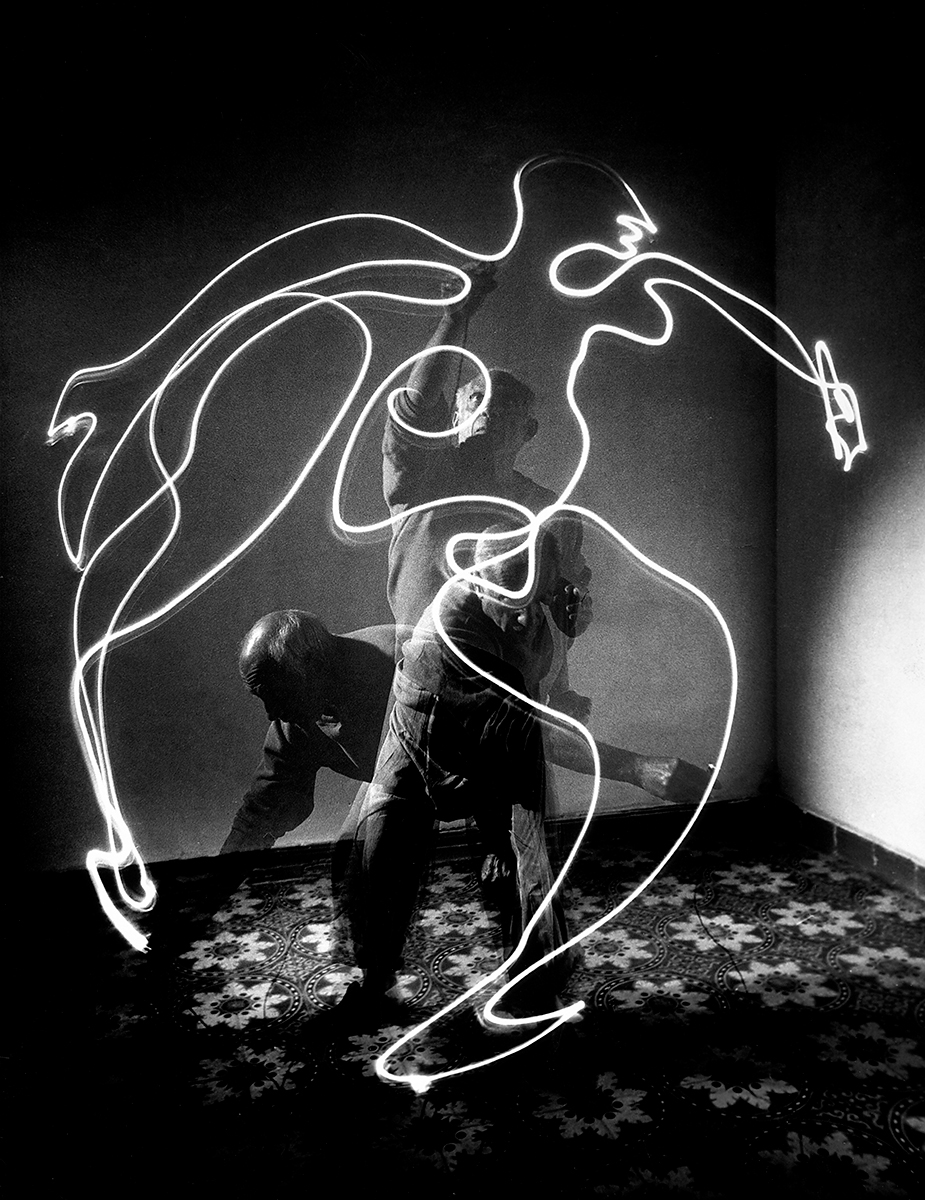

Collector. This is how one could resume the lifestyle of Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) – and no, we’re not referring to his countless love affairs. According to an article published by BBC Culture, the Spanish painter was a true hoarder: “He surrounded himself with garbage, knowing that even the most mundane and torn-down of items could be of artistic interest. He collected everything, from old newspapers to scraps of wrapping paper, to used envelopes, even tobacco cases, bus tickets, and paper napkins. When the piles of stuff became too high on his tabletops, he would clip them together and hang them, like a chandelier, on his ceiling.” Everything could be used to create something. “We are what we keep”, Picasso would have said, who had an unusual work ethic (“Inspiration exists, but you have to find it working”, is yet another one of his mottos) for someone who came to the studio just before two in the afternoon. But, then again, that’s as valid as writing laying on the couch, with a cigarette in one hand and a cup of coffee in the other, with the weight of a deadline hovering on top. And that wasn’t something Capote said. We did.

Translated from the original article of Vogue Portugal's Creativity issue, published in March 2021.

Most popular

.jpg)

Relacionados

.jpg)

Anna Wintour e o presidente da câmara de Milão, Giuseppe Sala, revelam a localização do Vogue World 2026

24 Feb 2026

O que lhe reservam os astros para a semana de 24 de fevereiro a 2 de março

24 Feb 2026