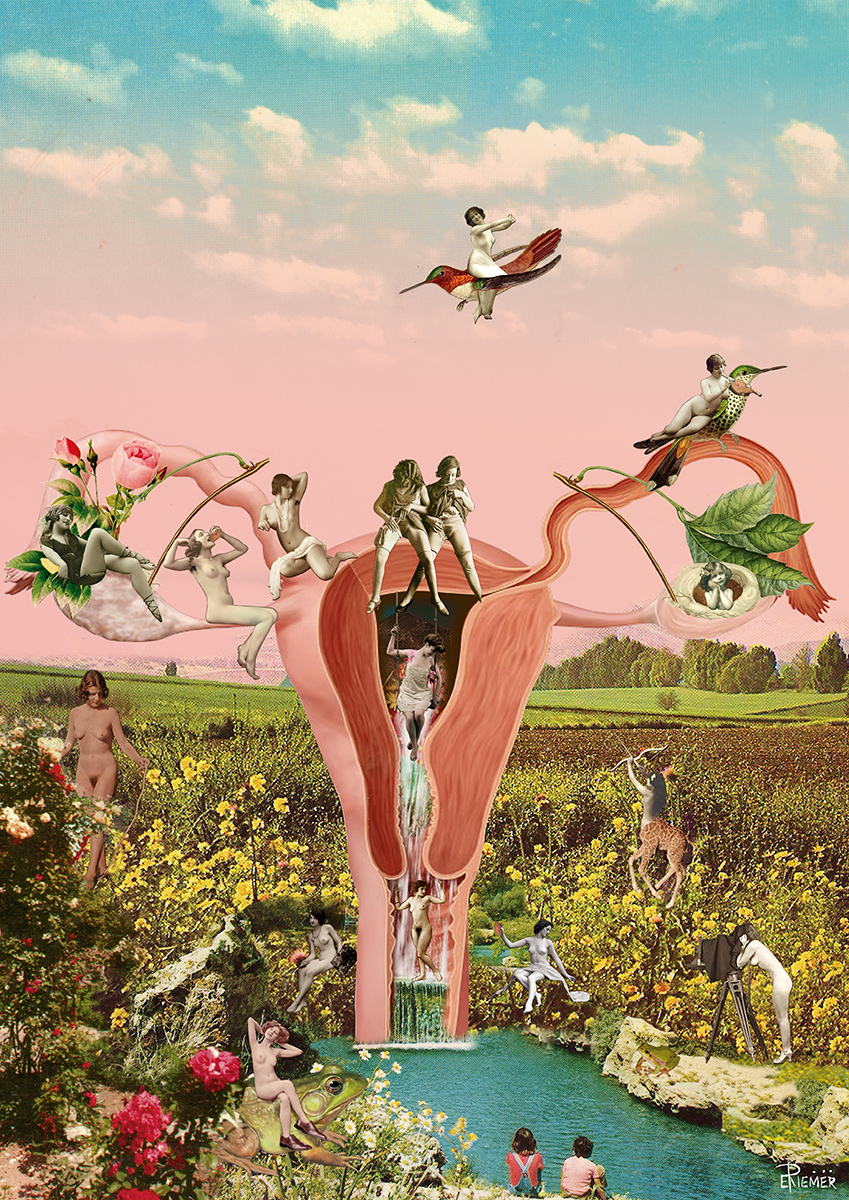

“Is the lady dancing, with a date or resting?”, the man questions. The lady can dance, may or may not have a date, and will rest whenever she pleases. The lady rejoices in her conquests, collects partners, begins and breaks off marriages and can afford to hit the flirt dancefloor. The lady, the girl, the woman, empowered herself. But, as in any other thing revolving around the feminine reign, the lady – or that “vicious”, “wild libertine” – still cannot wield her sexuality as she pleases. She still has a bit of residual shyness about being “comfortable in her own skin” which, truth be told, is nothing but a huge turn off.

“Is the lady dancing, with a date or resting?”, the man questions. The lady can dance, may or may not have a date, and will rest whenever she pleases. The lady rejoices in her conquests, collects partners, begins and breaks off marriages and can afford to hit the flirt dancefloor. The lady, the girl, the woman, empowered herself. But, as in any other thing revolving around the feminine reign, the lady – or that “vicious”, “wild libertine” – still cannot wield her sexuality as she pleases. She still has a bit of residual shyness about being “comfortable in her own skin” which, truth be told, is nothing but a huge turn off.

“Women are machines for suffering”, Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) suggested to Françoise Gilot (France, 1921), one of his countless mistresses, with whom he had two children. After beginning her affair with the Spanish painter, when he was 61 and she 21, Gilot heard from Picasso the following words: “There are only two types of women - goddesses and doormats.” Marina, Picasso’s granddaughter, who in 2002 published a memoir titled Picasso: My Grandfather, recalls the treatment her grandfather gave women as a dark phenomenon, a vital part of his creative process: “He submitted them to his animal sexuality, tamed them, bewitched them, ingested them, and crushed them onto his canvas. After he had spent many nights extracting their essence, once they were bled dry, he would dispose of them.” The quote I chose to open this article with was not planned. While writing it I took a break and turned on the television, where I saw that a movie about Picasso was on. The scarce 15 minutes I had the (dis)pleasure of watching were more than enough to realize that Pablo Picasso was a pig – pardon my French. A great artist, an even greater narcissist and an unscrupulous macho when it came to dealing with the feminine gender. It all revolved around having sexual intercourse with those various women, it was only that and nothing else. The sex he stole from women, and his art – like the great artist he was, with an overflowing ego – were all that mattered to Pablo Picasso. And women, just like his granddaughter Marina put out in the open in her aforementioned book, were less than nothing. Or better yet: they were his sexual objects. Their vaginas should be – and, according to History, they were – always available and at the genius’s mercy. And now, finally, I can pin down the theme for this text, which would be something like: why can’t women do whatever they want with their bodies – from sexuality to the simple approach to flirt? The thing is, they actually can – we actually can -, but as History goes, when it comes to sexuality, women are not entitled to wants or needs. And what is even more confusing is that Picasso’s day and age were a century ago – one hundred years. One hundred. Thus, the reader could think right about now: “What a thought! Things are different now. Women today have all the freedom in the world to do whatever they want with their bodies. This is the XXI century after all.”

It is clear, it is obvious, that things have changed, it is beyond evident that the feminine sex is freer, liberated and full of drive, and even more turned on. However, there are still some “but’s” in the equation – it’s as if women were getting more and more comfortable with their own sexuality, but we’re not quite there yet, at least not completely. Otherwise, let’s see: “Although we are witnessing many changes, we still have strong castration roots in a recent past where women were undervalued and destined to take care of their household and families. We still often live our sexuality with guilt and don’t get to know ourselves that well. There’s still a long road ahead and formal sexual education can and should contribute to that change”, says Vânia Beliz, sexologist. She recalls how some people still come to her practice asking questions such as “if I use a man’s towel can I get pregnant?” She confirms that there are still many doubts and questions about the body floating around and that “the vulva is an area one should avoid looking at and of which we should feel ashamed of.” It’s fine, to ask questions is good and should be encouraged. And better yet if it goes along with a growing awareness of one’s intimate parts, even more so since this is a subject that includes the woman, her vulva and the sexologist – and what happens inside the walls of her practice, stays there. The problem is the jungle outside. The problem is when women want to experience all that sexuality in the exterior, it’s when women want to take the first step, it’s when women want all the sexual partners they feel like having, it’s when they talk dirty, it is when, and speaking in a chauvinistic and somewhat redundant way, women want to be “the macho” of the relationship. Or relationships. It’s not a matter of being able to or not, she can, but it’s never the same – after all, she is not him. The sociologist Bernardo Coelho goes on a historic retrospective, so we attempt to understand this sexual gap: “To answer that question, we must understand that the history of sexuality is also the history of men attempting to control the body and sexuality of women. Historically, it is that attempt – it has been that attempt – to control the body and sexuality of women. Let’s go back to the end of the XIX century, beginning of the XX century. At this point, sexuality – especially women’s – was not understood, not in a legitimate way, outside of the most restrict romantic contexts, such as conjugality and relationships. But within such relationships, the woman was a mere transactional object between her father’s law to the one of her husband’s, in a way that her will or personal expression were annulled, even when choosing who her life partner was going to be, her husband. In a way, it is to women that we owe the construction even, the importance and centrality of love, in contemporary societies, in the sense that the feminist movements that occurred during the first wave were the ones that made love a central aspect of peoples’ lives. And then, love also appears as a feminist and as a women’s claim where they expressed their need to be able to decide, according to their feelings and wishes, who the person they want to live with is. Therefore, ever since the beginning of the feminist fight which tackles the subjects of the body, sexuality and who they want to share that sexuality with, that is present. However, there is always a great deal of tension involved too. A political dispute over the control of women’s bodies and sexualities, a control which is – and has been for a long time – associated with the attempt to ensure legitimate offspring. Bottom line is, to treat women, their bodies and their sexuality as an object – reducing them to domestic entities with little to no say in things -, was the same to men as ensuring that their descendants were legitimate. That the sons of those women were, in fact, theirs”.

Times change, mentalities change, and the question I ask is this – let’s suppose that, we would think, as we naturally would, that the winds of change have brought some joy to the female gender (and their sexuality): “During the second wave of feminism – around the 60s of the XX century – things changed profoundly, and the political agenda of women includes the affirmation for the control over their bodies and sexuality. An agenda that is reinforced with the discovery of the contraceptive pill, which allowed women to be more in control of their bodies and sexuality. It’s obvious that this battle is not fought without resistance, and that is the ultimate difficulty”, Bernardo Coelho finishes. And this is where things get (even more) complicated, as we introduce the (historical) matrixes of perception of what is appropriate or inappropriate. Of what the evaluation grids dictate relatively to what it means to be a “man” or a “woman”, of what is appropriate for a man and for a woman: “This tense logic, always while attempting to control women’s bodies and their sexuality, (historically) produces what we can call a moral double standard which prescribes contained sexuality to women, controlled, much similar to decorum, shame and even a bit of chastity… And that is a way of controlling the behavior and sexual experimentation of women and their bodies. In the end, the existence of that castrating morality is a way morally and socially controlling her bodies and sexuality”, the sociologist adds. All we need to do is think that, to this day, a woman who has had multiple sexual partners throughout her life or successive boyfriends, outside of a romantic context, incurs in serious risk of insult and accusation. The same does not happen for men – quite the opposite, since that man would be seen as a super-hero in the sack (in the eyes of other men, of course). And he continues: “In contemporary societies, what happens is that women are still put in a rather awkward place. Due to this moral double standard, this contention logic, of a sense of morality that prescribes to women sexual restraint, has not gone away. It is there, inclusively, in the great cultural narratives dictating what women or their sexuality should be. On the other hand, women feel, live, want to live and claim for themselves a way of being sexual that is more expressive, the possibility of putting forward what they want or don’t want in the field of sexuality and of living it as freely and equally as men do.” To sum up, the truth is that, despite all the path that was drawn by the feminine drive and pulse to this day, we’re still missing that “tiny bit”. It is enough for women to carry the feeling of culpability in their DNA, as well as having spent their existence being restricted by rules – the ones of society, themselves, or of men of the likes of Pablo Picasso. Pleasure is universal and it is at the service of all human beings – whether they have a penis or a vagina. It is also up to women to know how to enjoy themselves and rejoice in it – without depending on others to do so, let’s put it that way. Vânia Beliz states that there are still a lot of complaints about not reaching orgasm that come to her office: “But I’m not surprised. In many cases, the lack of awareness is the reason why people can’t reach completion, but stress, anxiety and chronic diseases might also be causes for lack of pleasure. The way we are educated also plays a big role here. If we learn about sex as something important and gratifying, we will increase our chances of enjoying it in a gratifying way.” To what I would add: and without fear of being happy.

Most popular

.jpg)

Relacionados

(1).png)