The past, the present and the future entered a bar. The employee, surprised by that unexpected visit, asked: “Are you those time periods that determine the history, and the choices, of humanity?” Each of them, turning to themselves, replied: "I am." And from then on, the world was never the same. Even today, we pay the price for this encounter of egos, mainly in the way we manage, and project, the cultural representations of our experiences.

The past, the present and the future entered a bar. The employee, surprised by that unexpected visit, asked: “Are you those time periods that determine the history, and the choices, of humanity?” Each of them, turning to themselves, replied: "I am." And from then on, the world was never the same. Even today, we pay the price for this encounter of egos, mainly in the way we manage, and project, the cultural representations of our experiences.

On the big screen she was Mammy. In real life she was Hattie McDonald. She went down in history as the first Afro-American actress to win an Oscar. In 1940, on February 29, the artist - who was also a singer, a comedian and a songwriter - received the award for Best Supporting Actress for her fabulous performance as the devoted, but sarcastic, servant of Scarlett O'Hara (played by Vivien Leigh, who took home the Best Actress trophy) in Gone With The Wind (1939). She was also the first black woman to be invited to attend the ceremony, but the racial segregation laws did not allow her to sit next to the rest of the cast. The Ambassador Hotel, where the event took place, had a strict “no-blacks policy”, but made an exception for McDaniel and her entourage, which would later be barred from the club where the post-Oscar party took place. It is interesting to mention this, almost a century later, because it means that no one hid these (shameful) facts from the fait-divers encyclopedias. Mammy, the eternal and outgoing Mammy, sat at a table at the back of the room, next to a wall, away from the team with whom she shared the plateau of what remains, to date, the most profitable film ever. She waited to take the stage to receive the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences award, the one that has no parallel yet for any professional colleague - the golden statuette. When her acceptance speech began, a breath of change was felt in the air. “This is one of the happiest moments of my life. I sincerely hope I shall always be a credit to my race and to the motion picture industry.” Mammy, the eternal and outgoing Mammy, spent much of her career playing the role of a maid - which caused her to be severely criticized by the black community, which nicknamed her “Uncle Tom”, a name given to someone who is willing to guarantee personal improvements even while perpetuating racist stereotypes. To this, she responded decisively: "Why should I complain about making $700 a week playing a maid? If I didn't, I'd be making $7 a week being one."

It was 80 years ago. The breath of change, after all, was just a breeze. The violent death of George Floyd, on the 25th of May, brought to light a wound that, in the hearts of African Americans, never healed: a wound caused by centuries of racism, segregation and prejudice. That is why, now, we are talking again about Gone With The Wind - the film adaptation of the novel with the same name written by Margaret Mitchell, published in 1936, an immediate bestseller and the Pulitzer Prize of the following year - that a layer of the population, whatever their age group, sees as a no brainer, a masterpiece, and that the opposite fringe sees as an attack on the past, and to the memories, of a community that (still) feels manipulated, and marginalized, mainly with regard to the cultural representation of its history. After days and nights of protests, on the streets and on social media, that united the planet with one voice asking for justice for the man who, for eight minutes and 46 seconds, was tortured for allegedly using a fake 20-dollar bill, the results began to arrive. Early in June, HBO Max announced that it was removing Gone With The Wind from its catalog for the United States. The decision came days after John Ridley, writer and screenwriter of, among others, 12 Years A Slave (2013), wrote an opinion article in the Los Angeles Times where he says that the movie “perpetuates some of the most painful stereotypes of people of color” and that it “glorifies” the United States' slave past, namely during the period that is portrayed, the Civil War (1861-1865).

But that is for the average viewer. Because Victor Fleming's epic counts for much more than that. An HBO Max spokesman told CNN that the film is “a product of its time and depicts some of the ethnic and racial prejudices that have, unfortunately, been commonplace in American society. These racist depictions were wrong then and are wrong today, and we felt that to keep this title up without an explanation and a denouncement of those depictions would be irresponsible.” The movie, which eventually returned to the catalog, is now presented “as it was originally created, because to do otherwise would be the same as claiming that these prejudices never existed”, but with a disclaimer that warns that it “denies the horrors of slavery”, in addition to two videos discussing its’ historical context and “a denouncement of these same representations.” HBO Max guarantees that, for the channel, it is important to promote the dissemination of the past, because only this will ensure a less divided future. "If we want to create a more just, equitable and inclusive future, we need to first recognize and understand our history."

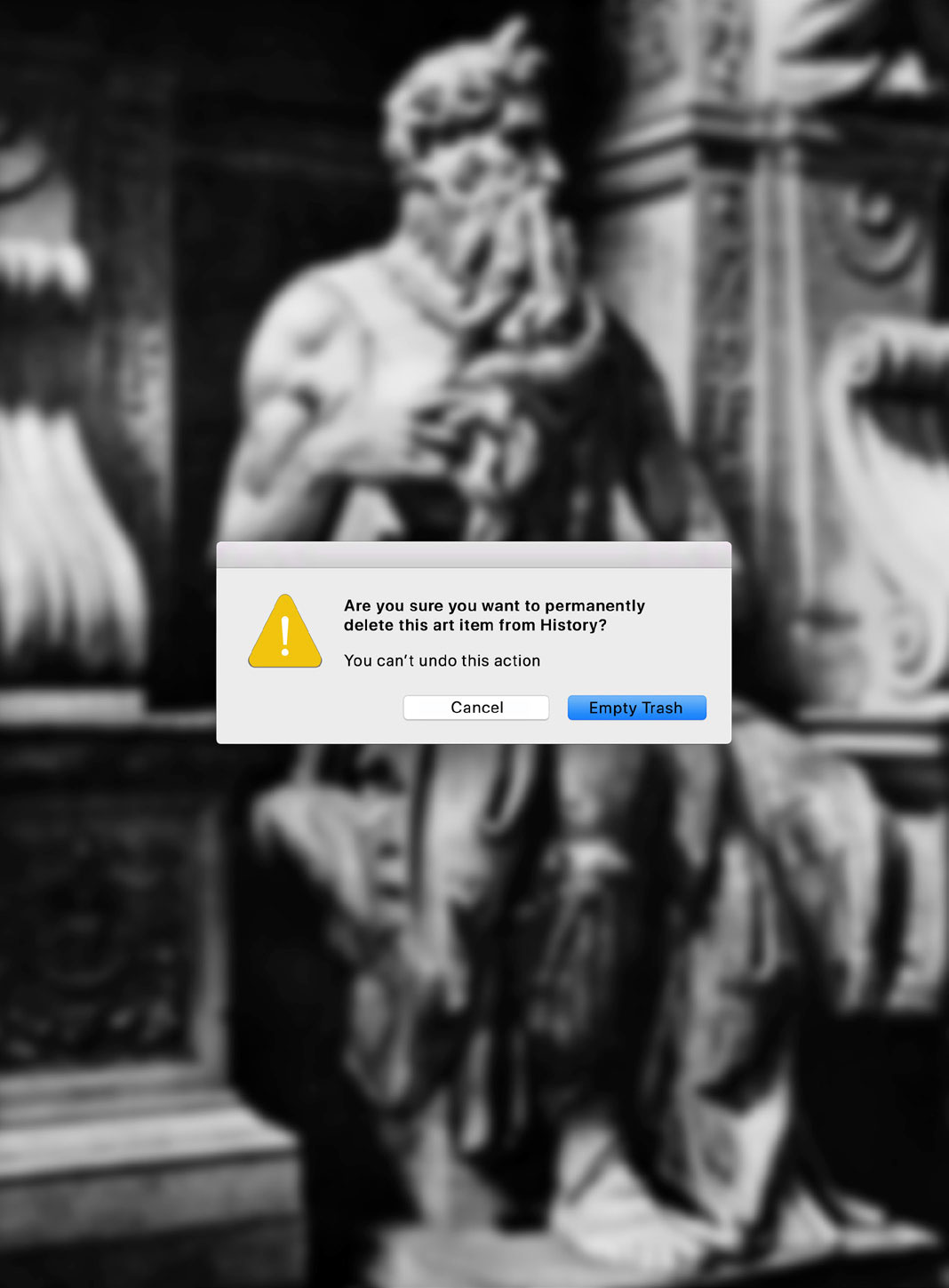

Perhaps this is precisely the crux of the matter. We are at a crossroads where present, past and future come together. The example of censorship of Gone With The Wind is one of many, as several programs have been pulled for the alleged practice of blackface: the Little Britain comedy series is no longer available on platforms such as Net ix, BBC iPlayer , BritBox and NOW TV; Hulu, for its part, withdrew an episode of the third season of Golden Girls, one of the greatest hits of the 80s, where the characters Rose and Blanche appear with clay facial masks and are confused with black women; the same destination had 30 Rock, Scrubs and Community, which were removed from the respective streaming servers for “improper behavior”. And this is just "in the non-real world." Because, in everyday life, more immediate things happen. All over the world, statues of historic figures were vandalized - in the USA, several monuments to Christopher Columbus, in Portugal, to Padre António Vieira - and, from one moment to the next, news spread of essential products that decided to change their name and logo. In the US, well-known Aunt Jemina, which has been making pancake flour for 131 years, announced that will be doing an extreme makeover. In a statement, the brand explained that “Aunt Jemina's origins are based on a racial stereotype [all images on the packaging are variations of the figure of the black maid, inspired by Nancy Green, a slave from the Civil War era]. "While work has been done over the years to update the brand in a manner intended to be appropriate and respectful, we realize those changes are not enough.” After that, also Uncle Bem rice, Mrs. Butterworth sauce, Cream of Wheat flour and Eskimo Pie ice cream took the same step.

Are we all mad here? Is it really time to change the names, erase the mistakes, and rethink the stories? We asked the question to Bernardo Coelho, sociologist, researcher and university professor. “Recent events refer, on the one hand, to the diversity, plurality and complexity of historical events, their actors and protagonists. On the other hand, they refer to unequal and lasting consequences of these events and this unique way of telling the story that obliterates the experience of black people, or Indians, for example. We have read, learned and seen the story portrayed always from the same narrator, from the place of the same protagonists, as if historical events were or had been unidirectional and had only a single protagonist. Basically, we have learned and read and seen the story always told by the same narrators. And, almost invariably, these narrators correspond to the white man. What these events reveal is the need to let the diversity of narrators of the past events emerge. Ultimately, these events around symbols of the past are visible forms of a struggle for the legitimacy of the production, conception and visibility of history, its events and its unequal consequences for the different protagonists involved.”

It’s that fateful meeting at the bar. Over and over again. “Basically, the overthrow or vandalization of statues will be the visible face of a movement of visibility for people who historically have been denied access to the place of protagonists in history, unable to be narrators of history and their lives. These acts are not erasure from history. On the contrary. They will be, on the one hand, demonstrations against the systematic devaluation, discrimination and silencing of their lives (which we have become accustomed to seeing as “other”, as if they were mere secondary actors in social reality: in films or in subordination, as they appear represented in statues, for example). In this sense, neither the history nor the present is erased. On the contrary, they add more knowledge about history and the present.” In addition, stresses Bernardo, these recent events are, above all, a response against “actors in history who appear as symbols of oppression and erasure of the lives of black and Indian people. In this sense, these acts will be physical forms of claiming an equal place in the present and in the possibility of building an equal future. It is a way, also symbolic, of [guaranteeing] the visibility of their lives now, because now they remain hidden and discriminated against. [...] In fact, all this is as much about the past as it is about the present, as it implies a deep confrontation with us as individuals, but above all as a community (with our distant past, but also with the recent past and the present).”

What will be the best solution then? Is there a right side and a wrong side? Is there someone who is right and someone who is thinking badly? Can we continue to enjoy Gone With The Wind or does it make us bad people? “From a practical point of view, does this mean that statues must be removed, streets renamed, films hidden, erasing the historical and public record of certain events, protagonists, or certain forms of artistic expression? Because I don't think that these events have to be erased or censored from history, I see no need to remove statues, to change toponymy, to hide films. In fact, to a certain extent, making this withdrawal from public space may mean bleaching the past, that is, a deeper concealment of the violent and discriminatory past. As to what to do, I have more questions than certainties, but one of the possibilities is to contextualize what is seen. For example: creating captions for the statues and toponymy, clarifying who these figures were and what they did, as in Bordeaux, or making little warnings about the contents of certain films, as did HBO Max. In a way, the attention we now see around the forms of artistic expression and cultural production are related to the fact that one begins to recognize in the other a protagonist and not just an object.” Dear Hattie McDaniel (To call you Mammy again is to fall into the error that you were just that, and nothing more), we will never forget you. Signed, present, past and future.

*Originally published on Vogue Portugal's The Madness Issue.

Most popular

.jpg)

Relacionados

.jpg)

Anna Wintour e o presidente da câmara de Milão, Giuseppe Sala, revelam a localização do Vogue World 2026

24 Feb 2026

O que lhe reservam os astros para a semana de 24 de fevereiro a 2 de março

24 Feb 2026