Arts Issue

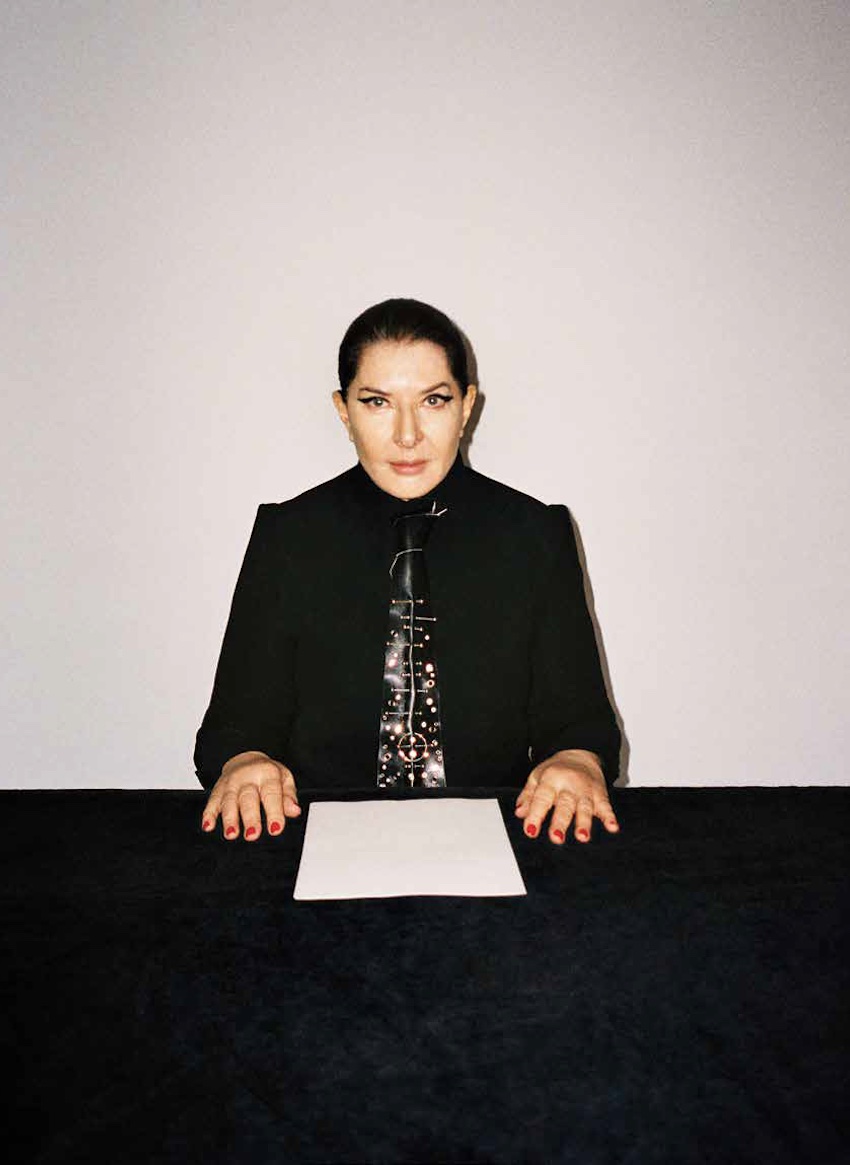

Marina Abramović's work may be immaterial, but the impact of her art performances remains with the public far beyond their duration. Talking about the artist is recognizing her immeasurable contribution to this artistic means in particular, and to Art in general, as one of its biggest contemporary names. Talking to the artist is realizing that her dedication is irreproachable and unchanging throughout her half a century career, that her honesty is untainted and that her humility is proportional to the magnitude of her talent and recognition.

“Seventy-seven”, Marina corrects me when I say that she looks incredible, no-one would believe she’s in her 70s. “Not 70, 77. On November 30th I will be 77 years old, in three years I will be 80. Can you believe it?” Her (good) energy is palpable, even on a pixelated zoom call that brought Lisbon and London closer together. Abramović, born in Belgrade, Serbia (at the time of her birth, still Yugoslavia) is in the English capital for her most recent exhibition: Marina Abramović, at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, showing until January 1st, 2024, is a show that recovers some of the artist’s works over the more than 50 years dedicated to the performance art movement, one that, even if you haven't yet had the chance to witness live, have certainly seen and heard about. Particularly, because of the way Abramović tests limits - her own, those of human beings and art - in favor of a message that she believes is bigger than herself: viral videos like her performance The Artist is Present (the artist sits at a table and the public is invited to sit, individually, without speaking, for as long as they want, in front of the artist), at MoMA, in 2010, in which her former partner, Ulay, after 20 years apart, sat in front of her, providing one of the most moving moments in the history of art (he was the only participant with whom Marina broke the rules of performance and touched his hand); to the heights in which she has risked her physical integrity and her own life (and there were many), as in the series Rhythm - in Rhythm 5 (1974), for instance, she jumped through a burning star and lost consciousness, without the public immediately realizing the seriousness of the situation until the flames came dangerously close to your body; and in Rhythm 0 (1974), she allowed the audience to interact, for a limited time, with her body, no restrictions, through the use of various objects as harmless as a feather up to as violent as a gun with a bullet (the escalation of aggression was so intense that many of her perpetrators avoided looking her in the eye, some even fled, when the artist ended her passive role and walked around the room) -, Abramović never stopped putting her body where her mind was, literally, nor did she waver in what is her artistic role. Aren't you afraid facing and stepping over those limits? “I think the question is more: what percentage of yourself are you willing to give?”, she rephrases it. “I always felt that 100% is not enough, I always wanted to give 150%, that extra 50% is what makes all the difference because the audience feels the effort, and it is through that effort that the audience connects with me. And this is above any criticism, because when you know that you give 150%, whatever the critics say, it doesn't change anything, because you can't do more than what you did. But if you don't give them the 150%, you feel terribly, because you know that you weren't delivering your abilities in full.” she stated, adding that “the moment you enter the performance, you don't feel any fear. Like a drunk man who falls and doesn't get hurt. Because there is something that seems to protect him. That feeling, when I'm at the center of the performance, is that nothing is going to happen to me. Only when there are things you can't control, like what happened to me this year.” Marina Abramović is taking about a recent scare, a few months ago, when she defied death in a different way than previous experiences: it was due to a health problem, and not for the sake of Art, that her limits were tested. It was the first time that fear had struck her.

“Four months ago, I don’t know if you know, I almost died. I had an operation and almost died, it was a big scare, they said that having survived was a miracle, so I feel like my life was given back to me.”, she shares, practically at the beginning of our conversation, the gratitude being felt unequivocally in the positive vibe of her voice. Known for taking herself to extremes, I ask what she felt different about this moment in which she cheated death compared to all the others in which she faced the end head on. “You know, in all my performances and in the difficult moments in front of the audience, I could control it. And I knew where the limits were, both physical and mental. But this [the health problem] was something that I couldn't control at all. And that was the scariest thing in the world. I was in a coma twice, I had to get nine blood transfusions, I had something they call saddle embolism, where instead of a single clot, you have a chain of clots which is potentially fatal. I might not have survived. I was in intensive care for about six weeks and when I woke up, the only thing they knew was that I had to stop all painkillers, or I risked becoming a vegetable. I had to feel the body and the pain, and I think that was very important, to force myself to get up and move. It was incredibly difficult, but this was what I knew well from my performances, the technique and the willpower, the concentration, and I think that was what saved me, in fact”, the artist reveals, while drinking tea, on-screen, simplicity and sincerity always punctuating her speech and being. “And when I managed to get out of this, I had this incredible feeling that, in fact, it wasn't my time to go, that I still had so many things to do. And that feeling of pure happiness when arriving here, at the Royal Academy and descending - on my own foot, not in a wheelchair - the stairs as the first woman, in the 255 years of the RA's history, to have an exhibition of her own... It was a moment of achievement I will never forget as long as I live.” It is, in fact, important to highlight that this ongoing exhibition in the United Kingdom is not special just because it is an incredible celebration of her journey: Marina is the first woman in more than two and a half centuries of the museum's history to occupy the main hall with a solo show. Not that, in her deep humbleness, she acknowledges this role as a female leader - she might know it, but, although grateful, she’s not moved by it: “I think it is mostly what people project onto me rather than what I I am, but you know, I don't want to stroke my ego too much here, because the ego is always an obstacle to creativity. Therefore, staying humble is very important. Other people may say that, but I don't see myself that way”, adding that, interestingly, on November 7th, she received the Women of the Year award, from Harper's Bazaar, and, on the 30th, the Men of The Year Award, from GQ Germany. “So I'm the woman of the year and the man of the year, and I'm on the cover of Vogue Portugal, I mean, this is something that happens when people are 15 or 16, but not at my age”, she admits, somewhat moved by the privilege.

Marina Abramović probably has some idea of how magnanimous her work is and as an artist, but overall she continues to be the girl who defied rules and who had an austere childhood and adolescence - until she was 29, she had a curfew at 10 pm, imposed by her parents, so all the performances she did “had to be before 10’o clock at night”, the artist once said in an interview -, plus went through the context of a country at war, to get to the individual she is today, someone still completely dedicated to her métier. Someone who, having already experienced what she experienced in her performances, remains a humanitarian with an unshakable faith in human beings, an artistic force that does not fade, a passion for life and endowed with a sense of humor and accessibility that dispels any intimidating feeling that one can have (which, I confirm, is unavoidable in the presence of the artist). When we talk about the opposite situation, if Marina has ever felt intimidated by someone's presence, she answers “only by one person in my life: the Dalai Lama. And not really starstruck, just because it's very emotional. In fact, I have another person, who was the Dalai Lama's first teacher, Ling Rinpoché, who has since passed away. And when I met him, he looked at me and flicked me on the forehead and I cried for four hours and I have no idea why. It was something that moved me a lot. And I think it was the kind of spiritual encounter [that left me speechless]. Other than that, I can be with the President of a country or with a cleaning lady, for me, they are the same. I am a true communist, in this aspect. For me everyone is a human being, everyone is equal. In the case of His Holiness, he has a kind of wisdom and knowledge and whenever I met him, we cross paths a few times, something dramatic happens in my life afterwards, it seems like there is a kind of cleansing. There's something... he's a different kind of human being. But otherwise, I mean, John Cage was a fabulous human being, but I wasn't starstruck, you know? He was in his kitchen peeling garlic, cooking chicken, and talking about life, and that was wonderful. But I wasn’t startstruck.” We are. Not only because looking at the artist is like remembering an entire work of performances (which is worth exploring in depth, if you still don't know her body of work in full), but because, as we listen to her, we realize that the privilege of being in her presence is not limited to the genius of the artist’s portfolio: her way of thinking and who she is as an individual is equally transcendent. Easily proven by the conversation, more than an interview, that follows.

Over the more than 50 years of your career, you have changed a lot and the world has changed a lot. Do you feel the way the public behaves and approaches your performances has also changed?

Performance art is already something you have to fight for, my whole life has been a fight, it's incredible, in the 70s, no one considered performance art as an art form: there was little public and only a few friends did it. And then, there started to be 20 or 30, but, as time went by, many artists started to give up on performance art, because it was too demanding. And besides, galleries and museums weren't very willing to show it, because it's such an immaterial art form, you know? Galleries and the market put a lot of pressure on artists to make something tangible, that they could show and that they could sell. So, at the end of the 70s, everyone turned to paintings, again, video was starting, so many tried audiovisual, photography also became part of the more mainstream art, but performance did not. And I never, ever gave up. And I'm probably the only one who still does it, at my age. Next month, I will premiere 7 Deaths of Maria Callas [an Opera project], directed and performed by me, so I continue to do this, and no one else. My generation gave up. And when that happened, there was also a loss of interest in this type of art, so now my followers and the people who actually look for my work are very young. I just did a workshop at the Royal Academy for kids and there were about 2,000, aged 15 and 16. They are the ones who love the work and they are the ones who bring their parents to see it, I never imagined this could happen. At the same time, there is something about my work that is its honesty - I don't compromise for the market, I never have - and the reactions you get from them are always very intense. Also because performance art is very emotional, and kids need emotions, because it's all about technology, about texting each other, there's zero communication. And when I did the workshop with them, I let them be silent, I let them look at each other, I let them feel and do things that no one teaches them. And young people really need to turn to themselves and their emotions. And I think they are the ones who will continue the work, because they are the ones who actually understand performance art on a much deeper level than my generation is doing at the moment. And even though I've been doing this for a long time, critics are torn between those who hate it and those who love it, but no one is ever indifferent to it, that's for sure. Those who hate it always ask the same question: ‘why is this art?’ I’ve been doing this for 55 years, and I still have to justify why this is art. It's always been like this. And the only thing I do is do my job to the best of my ability. But times have changed.

What do you think changed the most?

First of all, the biggest problem and what has changed the most over time is political correctness and democracy in art. Art is not democratic. You can't actually judge an exhibition by how many transgender or African-American or lesbian or non-binary people it has; what you have to judge is the content. What is the performance telling you, what is the idea behind it. I don't have problems with any gender in my life, I accept everything, I just ask that you look at the content, look first at what the artist is saying, which is the most important thing. And this has changed. You can't tell a joke, you can't say anything without being crucified. You know that the art we did in the 70s could never be done now. This whole part of art history wouldn't exist, because of political correctness. It's incredibly damaging to creativity. This is what I think has changed the most. And also, for example, now at the Royal Academy, when I'm doing the performances, it's incredibly complicated. For example, in The House with the Ocean View, performed by Elke Luyten now, an extremely demanding piece that we are revisiting, it’s 12 days without food, without speaking, standing in that structure, day and night, you can only drink water, and for her to be able to do so, there had to be a note from a nutritionist, a psychologist, the bureaucracy involved is incredible. And when I did it [2002], I didn’t have nothing. Thinking about these things didn't even cross my mind. I just did the work and that was it. This is how things have changed. And in a way, you have to make a healthy concession, but not too much so that you can continue to do the work. For example, Luminosity [1997], a piece on a bicycle saddle, which I originally made as a six-hour performance, can now only be 30 minutes long. Today, everything has different rules. Like Impoderabilia [1977], in which a naked man and woman stand facing each other in a narrow door through which people have to pass. And, at the time, we only had this narrow door through which you really had to lean against naked people to go through. And when I did that at MoMA, you had to have a door big enough to let wheelchairs through - and that's not the same performance, you know? And now, we chose to have a second door and you can go through the narrow one or go around to the other entrance. But what's happening now in the UK is people freaking out about naked bodies. What's wrong with naked bodies? So, there's all this negative coverage around the naked people, but at the exhibition there's a line of people to go through the narrow zone instead of going around. There is a waiting line and people complain about the nudes?

Your work has so many hidden layers, some that, I believe, you didn't even foresee when you imagined it. As an artist, are you often surprised by some nuances in your performances?

That's an interesting question, because you know that when your work is art and art is intuition... well, this will be a longer answer than I anticipated: do you know this exhibition at the Royal Academy? It's not a retrospective, it's more of a themed show, all the rooms have a theme, and show different periods, and when you're very young, you have the intuition to do some things, but you don't have the right well-being and knowledge, you don't even understand how deep it is and how far what you're doing goes, you need time to pass. And I have works from the late 60s and then works from the 2000s, which end up dealing with the same ideas, but from a completely different point of view. Because in the meantime your age has changed and there is something that comes with that that is in a way wonderful - and that's why I don't want to go back to a younger time, because I was suffering too much. Now, there is a wisdom that you didn't have and it gives you a different perspective on your early work, on what you are doing now and that is really special. For example, I learned things from my work, now, at 77 years old, that only time allowed me, I couldn't do it while I was doing it, because you need that distance. (…) By the way, I know you didn’t ask me, but can I talk about the situation between Israel and Palestine?

Of course, please do.

You know, when the war started in Ukraine, I was the first artist to make a statement in support of Ukraine, just hours after the invasion. This time, I literally receive a request every five or six hours to sign a petition for Palestine, a petition for Israel, to speak out on both sides... and I feel in catatonia, I can't move. This is the first time in my life that I can't share my opinion right away, I need time. They ask me to make some artistic work... but a work of art cannot be created in a hurry. When there was war in my country, it took me three years to make Balkan Baroque [1997], to gain perspective and understand what was really happening. It's the same thing here: you can't form an opinion, there are terrible things happening on both sides, they're both killing each other, it's such an incredibly difficult time in the History of Humanity, you know? First of all, what you can condemn is violence, in general. Killing people is wrong, regardless of which side it is, it doesn't matter which side is right or not. The only thing I can think of is something the Dalai Lama said, which is the core of everything: “only when we learn to forgive, can we stop killing.” And this idea of forgiveness is the basis of Humanity. We have been constantly making mistakes for centuries, not just now. If you think about all the wars this planet has been through... and forgiveness is something we never learn. And I know you didn't ask the question, but I was watching TV in the morning - and I avoid watching TV, because otherwise I have nightmares, but I watch it in the morning, and I was watching and thinking: 'Oh my God, this is the hell'. And this year is ending in such a terrible way, I don't think next year will be good.

On the matter of controversial topics, there is something on the agenda that has been talked about from time to time, which is the separation between artist and work, since many artists are judged by their personal conduct and their work suffers. What is your take on this?

For me, the artist and the work and the way he lives have to be in harmony. Of course, that's the idea, but it doesn't always happen. All cases are different. I'll give you an example: you read a book. And the book is fantastic and lifts your spirit, and all you want is to meet the artist who wrote this book. And you go to the bar and this is the guy who hasn't showered, smells bad, he's totally drunk and talking nonsense, and he's the writer of that book. And you get disappointed, and this happens a lot of times, but do you know what happens? I think about this issue a lot. It's just that, when you are creating, you are creating from your higher 'self', you are creating from the best part of yourself and that is what gives birth to something that is great, a great work of art, painting, film, whatever. But then, you can't keep that greatness. You go to your lowest, because we are all so many different things, we are not just one person, we have different personas within us. And so, you go to your lower side, because after you create something great, that part of you just wants to drink or, I don't know, do drugs or have orgies or whatever, because it's too much for anyone to always maintain your highest 'self'. You can see that at concerts, when you have a concert with 5,000 people and you see the singer getting all that energy and giving it back to the audience, and it's incredible, but the moment when the lights go out and the audience leaves, you have all this energy inside you and you don't know what to do with it, because you have no technique. And that energy is destructive, you'll immediately want to release it with drinks or drugs or whatever, because it's too intense. This is something that also concerns me with my performances, because when I perform, the energy is enormous. I turn to Tibete, shamans, to all cultures to learn how I can deal with this energy so that this energy nourishes me and doesn’t destroy me. And few people learn to do it. In my work, you know, I discovered that there are three Marinas that coexist: there is a heroic one, a true heroine, there are no obstacles, courageous, because as both my parents were national heroes, I have that in myself; the other is spiritual, I can sit in a monastery for months and that is very important for me, the energy and the spirit; and the other is the Marina of nonsense, who loves to eat too much chocolate, watch bad movies, being lazy... I accept these three Marinas and they live very harmoniously in my body and never fight. I balance the three a lot. But to answer your question: life and art, sometimes, miraculously, go hand in hand, other times they don’t.

Still on current affairs, and talking about work and artist, there is another issue that generates controversy, which is Artificial Intelligence and its influence on art.

I think technology affects not only art, but life in all aspects. Because artificial intelligence can be very interesting, but it can also be dangerous, depending on who is using it. For example, militarily, used by the wrong people can be completely evil. And I don't have enough information, but I think that technology and virtual technology have already taken over [our lives] in so many ways, we are affected by everything that is happening and it is always changing, I don't know what the future effects will be. But what I try to do in my work is to always have the human side, have the emotional side, so that people can establish a connection, as human beings and not as artificial intelligence. Because that's a pretty scary future. Even now, science fiction books from the 70s are today's reality.

There is a NASA study, carried out over the years, that says that 98% of children are geniuses, because they use their creativity to solve challenges - and that this percentage decreases with age, with only 2% of adults revealing these same traits. Do you think that creativity is something innate in human beings and that our social and educational system may be strangling it?

I think human beings naturally creative, but I also think the context in which they are born and grow is important. But what I find even more interesting to analyze is that they recently discovered that 80% of cave paintings were made by women, not men, which is unbelievable. It basically means that Art History began with women and not men. It's a fascinating discovery, because the need to create is prehistoric. They were sitting in the cave, taking care of the children, while the men went hunting and made art. It's an incredible discovery, you realize that Art has always been part of the human need to create.

You founded the Marina Abramovic Institute. Did you feel that there was a need for more training in this area of performance art?

After The Artist is Present, at MoMA, where I noticed the huge turnout of the public, and their reaction to the performance itself, I got up from my chair and thought: ‘this is the moment to educate the public’. I discovered a treasure, the treasure that is long-term performance. This kind of performance is different from all the others, because it's real, you can't fake it - three months later, it becomes your life. And, therefore, I wanted young artists to learn about long-duration performance, I wanted to create the Institute, I wanted to create the Abramović method, I also wanted to instruct the public on how to see long-duration work, because it’s not just you doing it, it’s also how the public can see it. And it's all these elements that you have to combine. We have a place in Greece, in the mountains, which is really incredible, and we do 10 workshops a year. And now we've done the South Bank takeover in London, where we showcased 11 artists from nine countries who are doing incredible long-form performances. The concepts are original to them, the only principle is that it is long-duration. And this is so important to me. And the Institute is now working globally. And it's the legacy of the performance that I've worked on all my life, I put so much effort into the performance and the performance is so important, because it's a living art form.

Do you have any r.. [she doesn’t let me finish]

No.

You have no regrets at all?

No. Oh my God, no. Everything happens for a reason, everything is a lesson, especially when you do things that you don't like, that you are afraid of, that you don't really want to do, they are the best things, because they are the things that teach you the most. Happiness is a state in which you don't want to change anything, it's always the same. But when you go through difficulties, that's when change happens. I am a firm believer that everything happens for a reason. For example, the seven years we had to prepare this exhibition [at the Royal Academy], we started in 2017, and the exhibition was supposed to be on a normal retrospective. We closed the catalog with the curator, finalized everything, and then Covid came. And we looked at everything… and decided to go back to square one. And this was a blessing for me, being able to redo everything and now I feel like it really is the best exhibition of my life. And it's so much better and it's not a retrospective anymore, they're pieces from different periods talking to each other and it's a continuity and people see them more than I ever saw them, in this way.

What inspires you?

Everything inspires me. Nature, life inspires me, I hate studios, I've never worked in a studio, they only exist to implement the ideas I take from life... I go on about my own life and the idea comes as a surprise. And when it comes up and I become obsessed and everything seems difficult... that's when I do it. But everything takes so much time. For example, realizing the Great Wall of China took eight years before they gave me permission; Seven Easy Pieces, at the Guggenheim, took 12 years to obtain permission; this exhibition [at the Royal Academy] took seven years… I mean, everything takes its time. But I never give up. And my next project is something I've never done before. I'm intrigued by making dance and connecting it to performance art, the limits of the body that dances and the limits of the body that lends itself to art. And I'm working with very old rituals from my country, the Balkans, and I'm interested in the eroticism and humor of countries like Bulgaria, Romania, Serbia, just to see what these rituals can bring and how I can put them in a new light and what we can learn from them. So, this is my Balkan Period and I will premiere the performance with a festival in 2025. So, starting next January 1st, this is what I'm working on.

Final question: Art imitates life or life imitates Art?

It's a bit of both, but I think Art reflects life, I wouldn't use the word imitate. Art reflects life and life reflects art.

Translated from the original in the Arts Issue, published November 2023. Full stories and credits in the print version.

Most popular

O que lhe reservam os astros para a semana de 27 de janeiro a 2 de fevereiro

27 Jan 2026

.jpg)

Relacionados

.jpg)

Armani, Annie Hall e um guarda-roupa vintage: uma antevisão exclusiva de O Diabo Veste Prada 2

02 Feb 2026

.jpg)

(17).png)