LSD, psilocybin, ecstasy, ayahuasca. From happy trips of the past to mental health of the present, could psychedelics be the future of therapy?

LSD, psilocybin, ecstasy, ayahuasca. From happy trips of the past to mental health of the present, could psychedelics be the future of therapy?

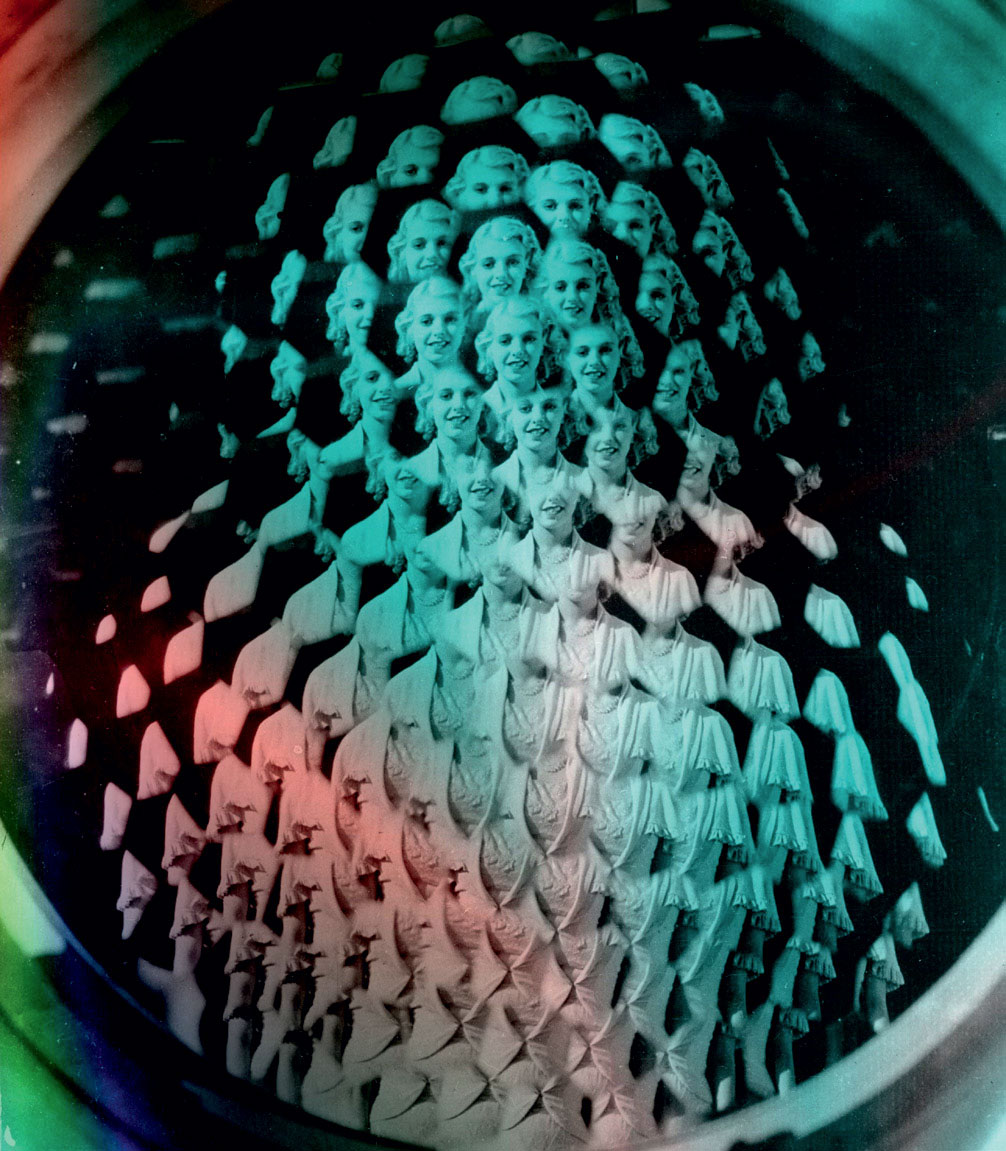

In 1967, John, Paul, George and Ringo gave the world what the world believed to be an ode to a psychedelic almost as famous as a certain Liverpool band. The theory turned out to be one of the biggest conspiracies about one of the Beatles' greatest masterpieces: Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds could only be an intelligent, but not subtle enough, short for LSD. Possible? Yes. Real? Not really. "I swear to God, or I swear to Mao, or to anyone you care about, that I had no idea that people could read it as LSD," John Lennon told Rolling Stone in 1970. Interview after interview, the musician was forced to clarify that Lucy was not an acid song. “My son came home with a drawing and showed me this woman with a strange look, flying. I said, ‘What is it?’, And he replied, ‘It’s Lucy in the sky with diamonds’, and I thought, ‘This is beautiful’. I wrote the song right away. After the album came out, someone noticed that the lyrics spelled LSD and I had no idea ofthat... But nobody believes me.” It is not surprising that the narrative was not convincing for an audience that, as the Rolling Stone wrote, limited itself to rolling their eyes: from LSD to psilocybin (a hallucinogenic compound found in so-called “magic mushrooms”), psychedelics are often associated to hippies and raves, to the mythical Woodstock and to trips so intense, mystical, and inexplicable, that they are able to unlock the creativity hitherto forbidden, reveal previously unknown horizons, and awaken previously repressed senses. Anyone who has embarked on this “journey” knows how impressive it can be. In 2008, 36 healthy volunteers participated in a study conducted by John Hopkins University in the United States of America, where they ingested a dose of psilocybin. After that session, 80% of the participants classified the experience as being among the five most significant of their life, on a personal and spiritual level; and half of the volunteers considered the experience to be the most remarkable of their lives so far. One year after this study was conducted, the results were confirmed and also validated through interviews with friends and family of the volunteers.

But that was then and this is now: fifty years after the The Beatles' “LSD” was discussed everywhere, and although they continue to be synonymous with a transcendent experience, psychedelics are beginning to be seen as something that science can explain. Or, rather, they are seen again as something that science can explain. “In the middle of the 20th century, two unusual new molecules, organic compounds with striking resemblance, exploded in the West. Over time, these molecules would change the course of social, political and cultural history, as well as the personal stories of thousands of people who eventually introduced them to their brains.” It is with this observation about LSD and psilocybin that the journalist and writer Michael Pollan kicks off How To Change Your Mind, a 2018 book that tells the somewhat unknown story of psychedelics, since the accidental discovery of LSD to the criminalization of these substances, including their reappearance in the 21st century and the author's own experiences with this type of drugs. For Pollan, and as he himself writes in an article published in The New York Times, “psychedelic therapy, whether for the treatment of psychological problems or as a way of facilitating self-exploration and spiritual growth, it is going through a renaissance in America”, a renaissance that happens both in underground environments and in institutions like John Hopkins, New York University and the University of California, where a series of studies with psychedelics have produced promising results. “I call it a revival because much of the work represents a revival of research done between the 1950s and 1960s, when psychedelic drugs like LSD and psilocybin were closely studied and respected by many in the mental health community as advances in psychopharmacology.” In fact, as he says, these two substances were even considered "miracle drugs" by the psychiatric establishment at that time. “Before 1965, there were more than a thousand published studies on psychedelics, involving nearly 40 thousand volunteers, and six international conferences dedicated to these drugs. Psychiatrists used small doses of LSD to help their patients access repressed material (after 60 sessions, Cary Grant famously declared that he was "reborn"); other therapists administered larger amounts of so-called psychedelic doses to treat alcoholism, depression, personality disorders, and the fear and anxiety of terminally ill patients who confront their mortality.” In the mid-1960s, when the psychologist, Harvard professor and psychedelic evangelist Timothy Leary declared that it was time for “turn on, tune in, drop out”, substances previously seen as “miracle drugs” became the USA's worst nightmare. “Drugs fell into anxious arms of a rising counterculture, influencing everything from the styles of music and clothing to the cultural ones, and, as many thought, inspired the questioning of the authority of adults that marked the ‘generation gap’. In 1971, President Nixon named Leary, who at that time had been removed from academic life and pursued by the law, as 'the most dangerous man in America', "explains Pollan. “That same year, the Controlled Substances Act was completed; it classified LSD and psilocybin as Schedule 1 drugs, which meant they had great potential for abuse and no accepted medical use; owning or selling has become a federal crime. Research funding has disappeared, and the legal practice of psychedelic therapy ended.” It is hard to predict what could have happened if the story psychedelics had taken a different course, but it is not at all foolish to think that science and medicine, as well as society in general, lost something in a way. “I think it was a shame that the previous generation of psychedelic drug researchers was abruptly stopped, because they were about to make very important discoveries”, defends Charles Grob, researcher and professor of psychiatry at the University of California, in Los Angeles, which spends part of its time studying a potential model of treatment with hallucinogenic drugs to cure psychiatric illnesses or cure addictions, in the documentary Have a Good Trip: Adventures in Psychedelics, that premiered on Netflix in May this year. "They were developing new models of treatment that we still think we should explore today, because they can bring a lot of promise and hope to people who suffer from diseases for which conventional psychiatry may not have great solutions."

From the potential to stigmatization, the promise of psychedelics was eventually archived, remaining in the shadows for the four decades that followed its criminalization - but as a case that has never been resolved, these substances have not been forgotten. “In the early 90s, well out of sight for most of us, a small group of scientists, psychotherapists and so-called psychonauts, with the belief that something precious had been lost, both for science and for culture, decided to recover it,” writes Pollan in his 2018 book. “Today, after several decades of suppression and neglect, psychedelics are being reborn. A new generation of scientists, many of them inspired by their own experiences of the compounds, are testing their potential to treat mental illnesses like depression, anxiety, trauma and addition. Other scientists are using psychedelics in conjunction with new brain imaging tools to explore the connections between the brain and the mind, with the hope of revealing some of the mysteries of consciousness.” This new generation, as Pollan defines it, has been exploring how promising psychedelic-assisted therapy can be. In December 2016, John Hopkins University published the results of another study with psilocybin, this time with 51 patients with potentially terminal cancer. The team's goal was to reduce the depression and anxiety that are usually associated with the risk of death, and the results showed that most participants experienced a significant reduction in depression and anxiety, and an improvement in quality of life. After six months, the changes were still felt - about 80% of the participants continued showing decreases in the depressed state and anxiety, and added improvements in their attitudes about life and themselves, in mood, relationships and spirituality to their experience with that drug. Although promising, this essay was not an isolated case. In 2011, and again in 2016, two studies conducted by the University of California and by New York University, respectively, showed similar results: when used to treat depression and anxiety in cancer patients, psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy was not only effective, but also safe. In addition to its potential in anxiety following cancer diagnosis, the use of psilocybin has been tested in areas such as tobacco and alcohol addiction, obsessive-compulsive disorder and severe/treatment-resistant depression - in the latter, and as observed in another study in Brazil, the use of ayahuasca drink resulted in significant reductions in symptoms of depression in 35 participants.

Gradually, the taboo also seems to be breaking apart. “People are looking for meaning, purpose, personal growth, development, mindfulness and expansion, and there is also an enormous desire to cure”, explained a researcher from MAPS (Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies) when asked why the mainstream needs these substances, on the Vice media website. “With psychedelics, we can sometimes borrow the courage to look at parts of ourselves that we don't want to consider because they are not beautiful. Psychedelics can also inspire us to personify love and celebrate. Human beings need celebration.” From The Healing Trip, the first episode of The Goop Lab series that debuted on Netflix in January this year, and which follows four members of Gwyneth Paltrow's lifestyle and wellness empire team on a therapeutic experience with “magic mushrooms” in Jamaica - although these substances are illegal in many parts of the globe, it should be noted that there are some centers for psychedelic healing, therapy and exploration, in places like Costa Rica, Mexico, Peru and Amsterdam, which allow you to have the experience in a therapeutic environment - to microdosing with LSD in Silicon Valley, used as a hack for hours on end of uninterrupted concentration, improved productivity and a greater sense of well-being - even though the microdoses had a considerable hype, and as Imperial College warned last summer, there is still no scientific evidence to support the reported effects - the world seems increasingly willing to “trust, let go and be open”. Even so, it is important to remember that we talk about illegal drugs in many cases, and whose "consumption" must be done in specific, controlled and guided environments.

“The role of the guide is crucial. People who are under the influence of psychedelics are extremely suggestible - 'think about placebos in rocket boosters', a Hopkins researcher told me -, with the psychedelic experience deeply affected by the set and the setting - that is, for the volunteer’s internal and external environments,” explains Pollan in the same article in The New York Times. “For this reason, treatment sessions typically take place in a comfortable room and always in the presence of trained guides. Guides prepare the volunteers for the trip that is going to happen, help them to 'integrate' the experience, or make sense of it, and put it to good use in changing their lives.” This is the type of response that researchers are eager to see in a future that may be closer than distant. At this time, and after receiving the breakthrough therapy designation by the FDA in 2017, MAPS MDMA therapy for post-traumatic stress is in phase 3 of clinical trials in the USA, Canada and Israel, which is expected to be completed in 2021, and to start phase 2 in Europe. The association's expectation is that the FDA will approve MDMA-assisted psychotherapy as a treatment prescribed in 2022. In 2018 it was COMPASS Pathways' turn, which received the designation of innovative therapy by the FDA for psilocybin therapy in the treatment of resistant depression that same year. Currently in phase 2, this study is being conducted in several parts of North America and Europe - Portugal, more precisely the Champalimaud Clinical Center, in Lisbon, is on the map of these clinical trials. Another name that is not out of the pack is that of Robin Carhart-Harris, leader of the Center for Psychedelic Research (the first of its kind, founded in April 2019) at Imperial College in London. In February last year, the researcher, who has devoted 15 years of his work to studying how drugs like LSD, psilocybin, DMT and MDMA work in the brain, was present at the World Economic Forum in Davos to discuss the potential of these drugs in contexts of depression, addiction and anxiety in terminally ill patients. Intrigued, the world continued to listen. In June of this year, Carhart-Harris wrote the article “We can no longer ignore the potential of psychedelic drugs to treat depression”, published on The Guardian's website. “It's been a while since we saw an innovation in mental health care, and psychedelic therapy works very differently from current treatments. Conventional medical treatments have dominated psychiatry for centuries, and although many people prefer psychotherapy, it is more expensive, difficult to access and arguably no more effective than drugs”, he defended. Despite all the progress, the researcher insisted that the stigma associated with mental illness and psychedelics needs to be dismantled - and what better time to do that than this? “Two silver linings of this pandemic are the fact that it invited an expanded awareness - and that people slowed down. Many will have looked at their breathing, contemplated their impermanence and that of others, and felt gratitude for care, love and life. If psychedelic therapy fulfills its potential, it will provide the same essential lessons. It will be up to each of us to decide how much we are willing to listen.”

*Originally published on Vogue Portugal's The Madness Issue.

Most popular

Relacionados