Stew. There you go. That’s all. You can turn the page. Because the stew (or casserole, in other latitudes), is the new beginning. Each day. With each dish. Onions, olive oil, garlic. A bit of tomato, depending on what you want. But that’s pretty much it. It could become tiring, as time goes by. It does not. For a cook, the new beginning that is a stew represents the birth of a creation that will please someone and thus, themselves too. It’s pure rebirth. Then why does it scare so many?

Stew. There you go. That’s all. You can turn the page. Because the stew (or casserole, in other latitudes), is the new beginning. Each day. With each dish. Onions, olive oil, garlic. A bit of tomato, depending on what you want. But that’s pretty much it. It could become tiring, as time goes by. It does not. For a cook, the new beginning that is a stew represents the birth of a creation that will please someone and thus, themselves too. It’s pure rebirth. Then why does it scare so many?

Travel journalism is often “ostracized” by more orthodox journalists. Because it changed drastically during the 90s. Readers no longer cared how many rooms hotel units had, if the cotton on the bedsheets was Egyptian, if the mattress was made of memory foam or at what time breakfast was served. Even less so which monuments or museums should be visited in each location. For that there were the Verbo Juvenil publications and the encyclopedias that came with the papers. With the “advent” of easy credit (the reason why there are quotation marks in the word “advent” is obvious), travelling became accessible to Portuguese families, even youngsters, who were keener on finding a secret spot, where only the better informed, such as them, had the privilege to go. Journeys off the beaten track, as they were called. Those who could not afford to visit more exotic destinations or even European capitals, hoped to dream when they picked up a travel magazine. How to find them? By accepting the invitation of the maître d’hotel to “have a drink” with his buddies, in a town that had been bombarded not even a handful of years ago. Or by sitting down for dinner at the camareira’s house, under the suspicious look of a severe Indonesian father. Or by tagging along the police rounds in Johannesburg, curled up in the backseat. This alone would provide enough material for a roll of creative writing, which would recall our own experience, that readers would be eager to share, and which allowed them to travel before they actually did. Even the famous Footprint and Lonely Planet guides began to carry a certain literary touch. Way before the journey itself, we were sunk in a thousand details that, more than contextualize, made us rethink the itineraries we had conceived so long before. It was in one of those that I discovered the New York based North American travel writer, Allison Tibaldi. Who was indeed also working with the New York times, CNN, Travel Channel, Budget Travel, Time Out New York, The Huffington Post, and yet another infinite roll of publications. At 22 years old, she moved to Italy. Can you imagine a New Yorker, who thinks mac and cheese and meatballs qualify as Italian food, that pizza is always two inches thick and that putting ketchup on spaghetti is not a crime, moving to a place where eating is as sacred as il sangue di Gesù? She reported, in her writing, that all she knew was that Italian menus were “prepared respecting the seasonal timing. The concept of garden-to-plate is natural, and the dining table is an extension of the yard and of the garden, with artichokes and tiny peas in spring, eggplant and watermelon in summer and thistles, fennel and cauliflower in winter.” Yes, this is one of the first signals. But let’s be honest about it, most of us thinks “with all that pasta, how are Italians not fat?”

It’s a sign we don’t know the first thing about Italian gastronomy nor of the way our transalpine friends have their meals. And if we don’t know it, when we’re separated from them by the mere Spain and France, imagine a New York girl who ended up marrying a guy from Tuscany and moved to Greve, in Chianti, the highest of landscape splendors with green fields surrounded by cypresses we usually see in desktops, to come across a place where the Renaissance seems to have lingered on forever, even at the dining table. Where there aren’t burgers, hotdogs, burritos, meatloaf nor previously fried fish now ultra-frozen in triangles, rectangles, and circles. Where butchers seem way too many for the people ratio because each household’s meat is bought, for many generations, to the family that owns the same butcher also for many generations, to concoct the true bible that are the absolutely carnivorous dishes of Tuscany, from Bisteca alla Fiorentina to Tonno del Chianti or to Porchetta di Monte San Savino (Google it, please). Like when a painter buys his materials always from the same art shop. And that’s just as surprising or even more so for a North American, who when she’s not eating a sandwich for lunch or a hotdog from the food cart across the street from work, after a breakfast of bacon and eggs and before the family dinner during which she has ham and the casserole of mashed-potatoes and peas is passed around (and for the vast majority of Portuguese people, who are completely mistaken about the transalpine diet), is the very constitution of the meal. How many courses are there, in the end, during an Italian dinner? One rarely finds antipasti at a family dinner table. But it is mandatory that restaurants have it, the same as what is done in Portugal before an order is placed, from olives to the incredibly sad butter packages or even tuna pâté. Curated meat (prosciutto and salami), mushrooms, cheese (provolone and mozzarella), artichoke hearts and anchovies, depending on the area. During a transalpine family meal, the first course is precisely that, the primo piato. And that is the only one in which pasta is present, in small doses, because it is destined to satisfy that first wave of hunger that is all eyes. Then comes the secondo piato. Meat, in the case of Tuscany. But only meat. A steak, for example (not any steak, but Chianina veal, of course). Any secondo piato must be accompanied of the contorno, made up almost always of vegetables. The great detail at play is that each of these courses is not random. The primo prepares the palate for the secondo, and the contorno enriches and refines it. There’s always a very harmonious connection between them, like a bridge that binds them with a form of subtlety that can’t be ignored. Allison Tibaldi recalls that one day she got a call from the school principal. It had nothing to do with linguistic limitations or behavioral problems. The matter was of another nature entirely: “Your daughter refuses to eat the contorno…” A tomato and basil salad on the side of a breaded fillet. The shock of whomever was on the other side, when they heard “my daughter doesn’t eat raw tomato” was inevitable. A full alimentary reeducation followed at school which the now grownup girl follows to a T, wherever she goes. It was a new beginning that changed her for life. Curiously, at least for those who enjoy floundering innocuous knowledge (or maybe not), we, Portuguese people, also had the antepasto (as starters were denominated), in times long gone (Camões refers to it in some of his writing), the sobrepasto and pospasto. No, we’re not in short of the pasto, a word that to this day defines everything that constitutes food. And how many of us have not already done, in Casas de Pasto, a memorable feast?

It was Christianity that messed this whole thing up. And before you stone me, allow me to explain… Christmas, for example, should not be in December. But in good old Europe, people were very keen on the festivities that celebrated the end of that terrible cycle when nights are longer and longer until the Winter solstice, that always occurs in the middle of December, and kickstarts the agricultural haven that is the return of the sun for a little longer on the horizon. So that the “barbarian” people would accept the Christian faith, the festivity was moved to a time when people were more predisposed to celebrate. And that’s how we came to celebrate New Year’s, with pomp, circumstance, and fireworks, on the first day of January. Wrong, again. Everybody that works, whether in an office, the industry or agriculture, knows that the beginning of the year is in September, sometimes even going over to October. Even the kids who go back to school. It’s the coming back from the holidays, meaning, the end of summer, that dictates the recommencement of orders, public services (try to get anything done in June and the response will be “Yeah, you know, now we’re almost in August, so I’m guessing September”), of everything. Even more so, of activities that depend on the land. Now hold and behold, the gift of the Portuguese land. Here come the grape harvests. Vegetables were dried and stored (no Portuguese household would have survived, through the times, without the dozens of “species” of beans or chickpeas”, tomato plants are having their last hurrah and one must conserve their fruit in either jams or pulps that allow us to enjoy them throughout winter (Portuguese people have not yet learned how to dry up tomato, like the Italians, as they already do with garlic and onions), peppers and pumpkins are still sun-drying, just like peaches and plums, berries and raspberries are turned into sweet jams, grapes are still around and some melons (the green ones) can last until Christmas.

From the sea we get what constitutes one of the biggest pillars of our gastronomy and, before the advent of freezers, fish were dried by the strongest sun rays, so that we could have them in winter, after having been soaked. Even the cheeses that are made around this time carry with them all the riches of the feasts these animals were fed and that enriched their milk. It’s such an abundant time that thirst is satiated with watermelon and hunger with everything else. There is such abundancy that it would be impossible to consume it all at once, even with the most scrumptious of parties. It’s Nature itself whispering in our ear, for a thousand years, telling us it is important to gather it for the following seasons. To restart big so the near future is assured. Modernity is saddened by the end of summer, of vacation, of long days and of the heat. European tradition unfolds in celebration… In Fribourg, in Switzerland, the Chilbi-Bénichon is celebrated with banquets, dances and lots of music, on the second Sunday of September. In Bern, the Zibelemärit (onion market) symbolizes the crops that will safeguard a less harsh winter. In the United Kingdom, Harvest Thanksgiving is still celebrated to this day. Even Halloween as we know it today was, in another time, the Celtic festivity Samhain, that celebrated the crops that would provide during winter. Just like the North American (and Canadian) Thanksgiving also has its origins in the festivities that Christians in New England organized to thank God for a good crop year (the first one ever would have happened in Plymouth, Massachusetts, and for the first time, around a hundred indigenous people shared the huge tables with their colonizers for a feast of wild turkey). This comes to demonstrate that Man has perpetuated traditions that mean one thing and one thing alone: we’ve learned, thousands of years ago, to interpret Nature’s signs. We follow them and assume that, year after year, there is a New Beginning. When we fear it, then it’s a sign we’ve grown apart from Nature. We’ve lost a connection that balanced the world. And that explains so much.

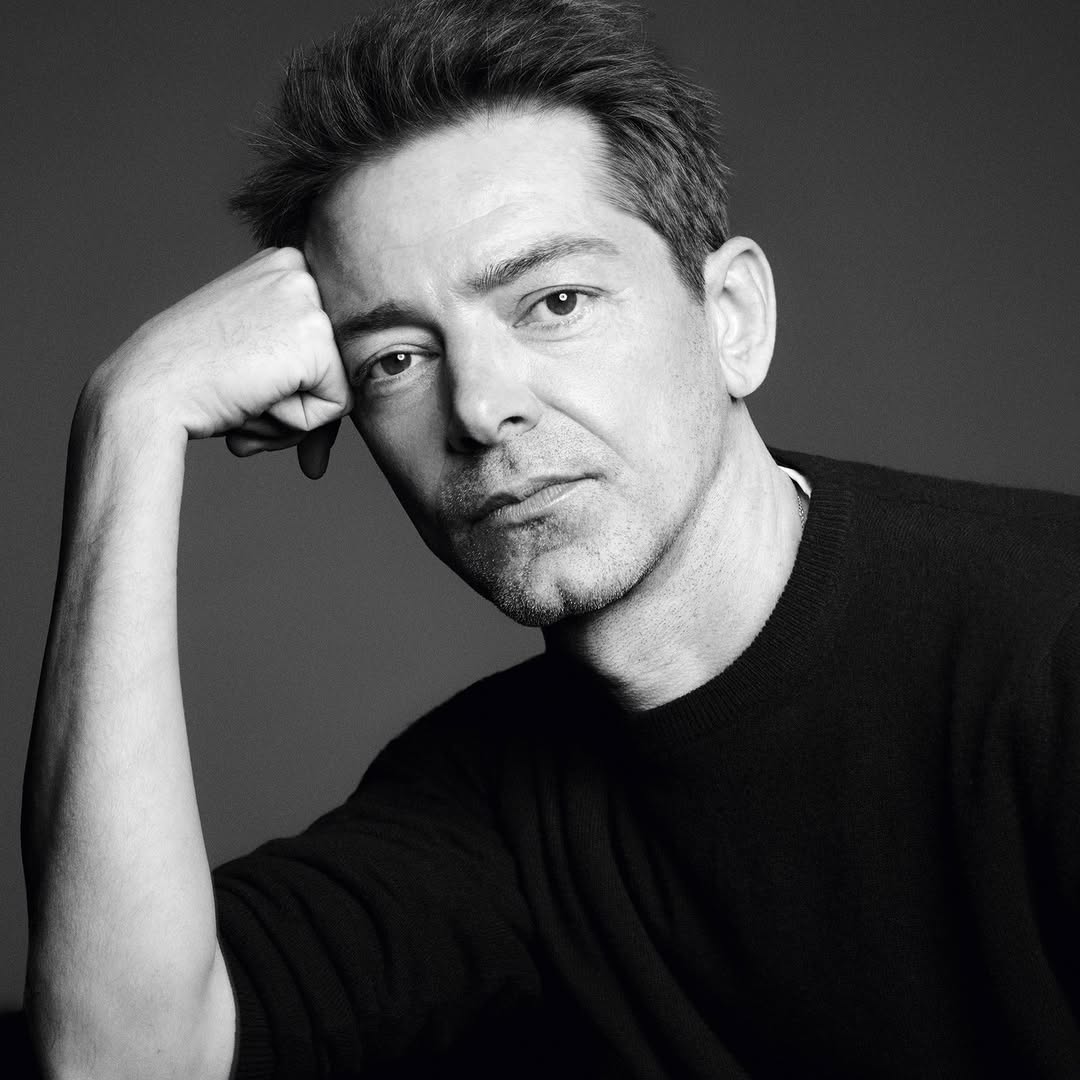

The example that follows is a message of hope (this would look great across a sky full of stars written in Comic Sans). It’s the aforementioned motivational tale that I won’t give over to Pedro Chagas Freitas because I have a ton of respect for the following gentleman. Hugo Nascimento carries on his belt 25 years on the restaurant business in Lisbon. Right in the heart of Lisbon. And we’re not talking of the kind that serves chicken wings on the oven or sausages with potato chips and an egg yolk. He is Vítor Sobral’s right arm. And his left, too. And his whole chest, those that stand tall and face the wind. I’ve known him for years and have always recognized his enthusiasm and commitment to projects such as the Tasca da Esquina (that then merged with the Peixaria da Esquina), that unmissable landmark in Campo de Ourique (and of Portuguese gastronomy elevated to its maximum splendor) and the Padaria da Esquina (Campo de Ourique, Belém, Restelo and Alvalade). Or with which he launched the Book of Sandwiches, that mandatory Bible that sits not on the nightstand but inside the picknick basket of any of those worthy of the task. Except life in the city is tiring: “Always running but always running late. Then, I don’t know why, perhaps old age, we start to consider a bunch of things. And I had been thinking about it for a few years.” I know how it is. We, the young folk in our forties, when we have something in mind it is very hard to get it out. Hugo is lucky enough to have his wife beside him, Joana, that to the repeating outbursts of the chef: “We have to go and start something from scratch”, only responded with another question: “Tomorrow?” With Alentejo running through his veins and a clear domain over its flavours, destiny was set. But it was during a family vacation, as the couple and their two children revisited annually Casas do Moinho, in Odeceixe, that it came about during a conversation with the two responsible parties for the project, Arnaldo Couto and Sandra Barbêdo, to refer that they were considering taking on a project in Grândola. To what they immediately responded: “What about doing it here?” A few months later, in the fall of 2019, the restaurant Naperon was open, which in such a short time, became a reference for the frontier between Alentejo and Algarve. About this new beginning, Hugo Nascimento is peremptory: “My children live in front of their school. They live the house at 8h28 and arrive at 8h29. I live five hundred meters away from work. I’m even thinking about putting up a red light there. Those with a sound alarm. Just to remind myself of Lisbon”, he jokes. But the quality of life that was won is undeniable: “I’m with my children, in one day, as much as I would in a whole week before. And I’m incredibly focused on my work, as I have always been, but here time goes by slower. I’ve won back years. It was the best decision of my life, without a shadow of a doubt. It’s a family project, and we have all embraced it, as a family.” To sum up, it’s happiness. And it shows. It’s hereby demonstrated that new beginnings are only a pain before they come to be. When we haven’t even started again. Meaning, when we’re still debating. Tomorrow will be the day! Then, after many years, we’ll look back with a smile. Except that smile will be in the present. A present.

Originally translated from the New Beginnings issue, published September 2021.Full credits and stories on the print issue.

Most popular

Editorial | The Naif Issue, fevereiro 2026

03 Feb 2026

Relacionados