Love & Hope Issue

We all know that Christmas is a time for sharing. As a very old slogan, our parents and grandparents heard it at Midnight Mass. We modern people hear it on the radio, see it on TV, and read it on billboards during traffic jams. And for the rest of the year? We don't cook or eat?

Each story is a piece / Cut from the heart / Of a man who at work / Shares life and bread / The lives you defended / And the bread you shared / Are tears you drank / From the eyes of a sad people." These words by José Carlos Ary dos Santos, sung by Carlos do Carmo, have never left my mind since. It was time to sit down in front of the TV to watch the series. And if, in that distant year of 1980, the gap between the lives of people in the big cities and the interior of Portugal was still glaring, what can we say about the first half of the 20th century, to which the episodes that Fernando Namora wrote so well in Retalhos da Vida de Um Médico, a literary work published in two series (1949 and 1963), which won the Vértice prize, was adapted for the cinema by Jorge Brum do Canto in 1962 (before the publication of the second series of the book) and eight years later, for RTP, can be traced. For twenty years, the author was a provincial doctor. At a time when it was the doctor who went to the sick and not the other way around, which meant he had to travel to the most remote villages in Portugal, Namora created a social portrait of a deep Portugal, miserable, hungry, malnourished, backward and unthinkable in the eyes of the most distracted city dwellers. Places that were lost in time and have remained there, more averse to science than to belief, their witches and their remedies for all kinds of ailments, bleak wildernesses with the highest infant mortality rate in Europe, apart from anything else, sometimes from hunger, sometimes from cold. The hardest part of being a xôtôre was being accepted by the community. Then there was the difficulty of getting paid for your work in places where money was non-existent. Potatoes, eggs, chickens, rabbits, and, at Christmas, lambs and cabbages and all the things that the villagers considered fair recompense for the work of the person who, after the cure, was already entitled to a more respectful xelentíssimo xôtôre. These were honors only reserved for the two most important personalities in deep Portugal. The letter carrier, who brought them the good news of their emigrated family (if not the information that a son had died in the colonial war), and the doctor who, little by little, they realized was alleviating more than a lot of their pain and sometimes saving their lives. They were therefore entitled to the most valuable thing there is: the fruit of the labor of the generous land. Being able to take home eggs, which were sometimes the only possible protein, or even animals that would provide the food that those people so desperately needed, was something that incurred a much greater expense for those households than today, with record interest rates, would be the house rent. It meant taking bread out of the mouths of their children, who ate tired horse soup for breakfast to help their parents in the fields to make ends meet. A people who, in their greed, were certain of a tomorrow, shared after all. It was all they had left.

For now, let's outline some etymological differences, in ascending order. Because sharing is just that (and that's all it is). Sharing already implies, by the prefix, that we do it with someone. At the top of the potential of the act, we have the term repartir, which indicates that we "leave" again. The Spanish also share, which is natural because they're from southern Europe, warm-blooded, and with their hearts in the air, the French only "share" because the verb partager contains it and the Italians, of course, had to complicate matters with their condividere, which has a kind of "conditions to see" in it, which perhaps has something to do with the joy we feel when we share. By now, you're expecting a long dissertation on the festive season and how it's a time for family sharing like some hypermarket jingle made up of close-ups of shiny king cakes cut by people with reindeer on their shirts. But that's the big problem that arises when we approach this subject. Because of this sharing thing, even once or twice a year, maybe very Catholic... But it's not very Christian. A Christian believes that Jesus Christ existed, raised the dead, healed lepers, gave sight to the blind, and dropped all those things that "commanded" us to break bread (which was the body), turn wine into water (which was the blood), forgive and turn the other cheek. Whereas Catholics also accept the Old Testament, which is just a translation of the Jewish Torah, added to by the powers that be at the time, to establish a vengeful, beastly God, who asks a young man to cut up his son to test his faith and sends floods and burns down cities like Sodom and Gomorrah just because people practiced polyamory and other debauchery. Take, for example, the legendary Queen St. Elizabeth, wife of King Dinis, who did not need to hide bread in her lap since it was she who instituted the cult of the Holy Spirit (celebrated during Pentecost), The Bodo, which has survived the Holy See's ban in the Azores islands, in some Brazilian cities, in Colares and, slightly altered, in Tomar, is a celebration in which the highlight is the crowning of a child (innocence and purity ruling the world), but also the freeing of prisoners and the making up of old quarrels, a share of meat (21kg) is distributed to the poorest and, of course, the body is held, a great feast where everyone is entitled to what is often lacking at home (on Terceira Island I've heard stories of the times when people used to go to the various bodies of the various parishes - or empires - to fill their bellies for several days). Sharing, sharing, or sharing out are mere everyday acts in the hearts of good people. Credit institutions and the State are already here to give and expect to receive in return with every pay slip, which not many of us get. What about them? Do they have to wait until Christmas to eat?

Every night, when we're in the comfort of our own homes watching how to make the perfect cebolada on 24Kitchen, Praça Duque de Saldanha fills up with people with their hands outstretched in the direction of a van from which other, giving hands depart. I saw vans from the CASA and Noor'Fatima associations, one identified, the other uncharacterized, and a long line of people. I naively expected to see people in rags. Nothing like that. Well-dressed people in well-cut blazers, many elderly people, two mothers with children on their laps, one with a small child in her hand, some immigrants with a Glovo backpack as their eternal appendage and a bicycle by their side, who sit on the steps of Avenida da República as soon as they receive the bag with soup, water, and bread, eating with greed that leaves no doubt, saving the piece of fruit for later. Tanvir is Bengali and pays €400 for a bunk bed in a room with three others (bunk beds), at least until his colleague manages to pay his share, which is €200. "He's been here for a month but he's only been driving an Uber for a week," he says, making light of the situation: "We always have rice at home. Sometimes there's not enough to put on it, but not hunger. Hunger is there." A little way away, Rosa (not her real name) is on a park bench feeding her daughter soup. She has crumbled half the bread to make "soups", eats the other half, and smiles: "Yes, I have a job. And I manage to make a living during the day, but when night comes, that's the way it has to be." She was born in Guinea but has been Portuguese since she was 18. Between her daughter's babysitter and the rent on her house, a long way from here, she has enough left over for a social pass. Once a month she is also entitled to a "basket" donated by her parish council, on the Sintra line, where she goes: "By train, of course." Carla (fictitious name), 45, comes "on the sly" because she tells her two children that she's going to the takeaway: "I and my uneasiness are enough. There's no need for them to have this weight on their shoulders or shame at school. They have a roof over their heads for who knows how much longer." She takes the subway to get here and today she's more nervous because the microwave broke down the day before and she'll have to reheat the soup in the pot, but she doesn't know if the gas canister will be enough for the morning showers. The most impressive case was that of Zé (a non-fictitious name because we have them in Barda), who allows me to take notes of the conversation and, before I sit down on the same bench in the garden in front of a designer store, asks: "Are you served?", which discourages me. He's holding a kind of plastic box with roast chicken and white rice, which doesn't come from any institution. "A friend brought it for me." He does it almost every day especially on Sundays and public holidays, when there is no food distribution. It's a work colleague who once saw him in the "soup kitchen" queue at Anjos when he was leaving a Nepalese restaurant with his family. "On Sundays, I have lunch with them at the house and take a bath there, the kids call me uncle, they were all very impressed that night, seeing me in a suit in a place like that," like me, knowing that Zé is a salesman for a well-known company and sleeps in the car with the huge logo on the door. It's the classic case of divorce + child support + a prohibitive rent increase. He became homeless and is in the process of giving up custody of his children because "I won't have them in my car, I can't take them to restaurants or museums or even eat an ice cream." Zé refuses the cigarette I offer him because he's giving up smoking so that he can buy a "souvenir" for his children this Christmas, a PS4 game that he's already ordered from Cash Converters in São Sebastião, and explains: "Have you seen what it would be like if my ex-wife knew that I, living this shitty life, had addictions? I drink a coffee a day and a gallon from the company machine when I go there to hand in expenses, the financiers already know me because I'm so thrifty, nobody knows," because his friend Carlos, the one who works in the Marketing Department and who is waiting for him on Sunday for lunch, won't reveal the secret. He also left him two bananas: "They'll be my breakfast tomorrow. Then I'll shave there, in the mall's bathroom. The security guards already know me. And there are more cases," he says. And we're all starting to hear about them. So what kind of Christmas is this where the gulf between those who don't share because they can't (but ask if I'm being served) and those who can share nothing is getting deeper? Scary, this Ghost of Christmas Future, dear Dickens.

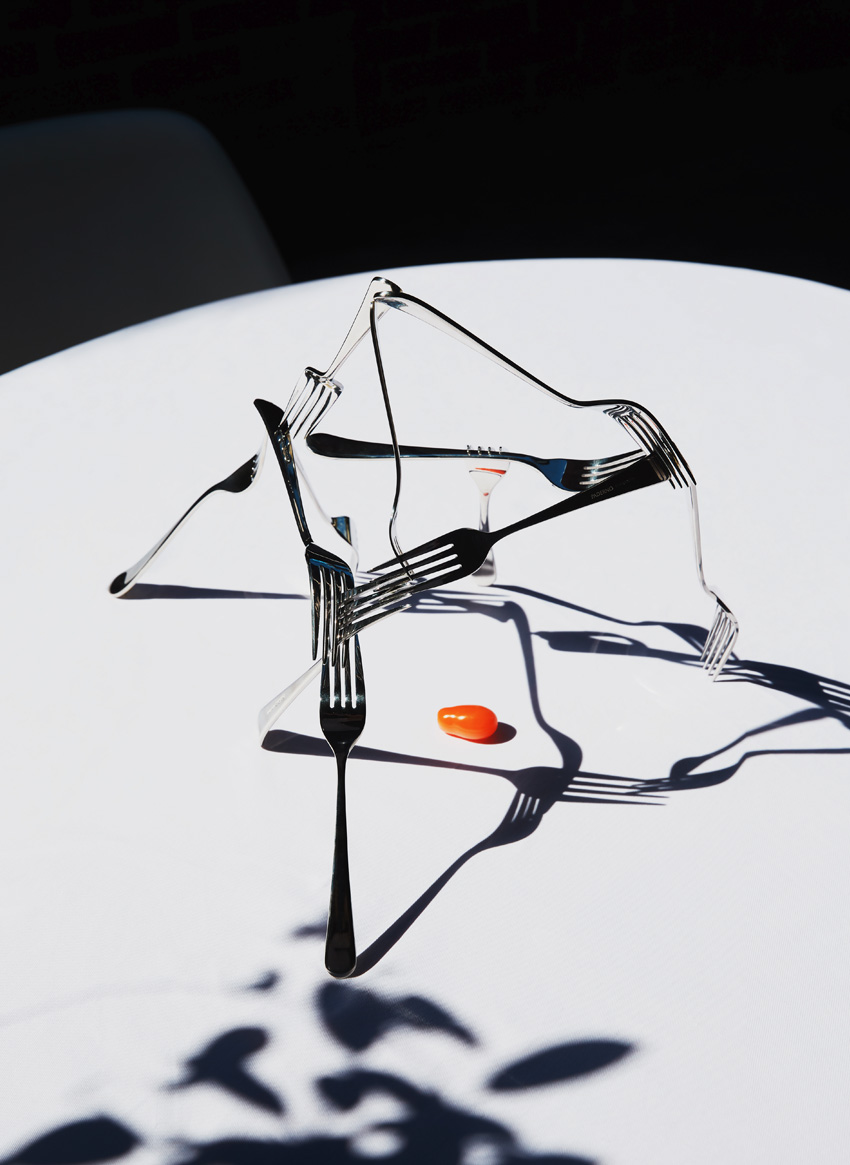

Once, at Taberna Moderna, a pleasant temple in Campo das Cebolas where the "gin fad" with which food is accompanied was born, the owner Luis Carballo, a warm and smiling Hermano with a sharp sense of humor, creativity to the fore (he paints, he photographs, the damn man has carpenter bugs) and a "vespis- ta" companion, thought I should try the Huevos Rotos with Icelandic Cod Chips and the Cuttlefish Rice with Ink. He served me a little of each, then helped himself and, when he saw the look of astonishment on my face, he guessed what I was thinking and declared: "All the dishes here are for sharing, that's the spirit." I looked at the menu and concluded that the prices were not at all expensive for the quality of the food. Luis chewed and declared: "You eat here. And what else is eating if not sharing?". It hit me. And I hate it when I see the obvious when it's always been right in front of our eyes. Because it's a sign that we've been "evangelized" to follow the opposite path. It is therefore urgent that, in the modernity that plagues us, we realize that the acts of cooking and eating have been synonymous with sharing since the first humans divided the proceeds of their hunt among all the members of the group. Or a few million years later, they shared the harvests of their crops. Let's leave for the distant future, when we'll be so indifferent to the suffering of others, the spirit of Christmas that only affects us during the season. Let's continue to cook with gusto for our friends every weekend, or almost every weekend. Let's accept more invitations to barbecues or Sunday lunches with big pots in the center of the table, sardines in the summer, and chestnuts when the cold hits. Let's give our mother the pleasure of welcoming us, with her best cutlery and embroidered tablecloth, for the seasonal favada in May. We gather in the work pantry for a lunch where everyone tastes everything they've brought. Let's sit down, as a family or with whomever, every evening, all together, in front of a slow food meal, something made in a hurry in the Bimby, roast chickens with potatoes from a packet, oven-baked golden browns or deep-frozen lasagna still resting in the aluminum corvette. But let's get together. Let's unite in this act of further sharing that is eating. Let's not eat in restaurants where they don't bring us two spoons for dessert, where they charge a fee when we share a portion, where nobody respects the religious nature of eating: Sharing, sharing or sharing every day, is, after all, doing what we like best. There are ways and places in the world where this is everything. I don't know how we got here, where nothing counts. Where a breaded sandwich at the counter satisfies our stomachs and our spirits. Perhaps we no longer value it as much as it deserves. Maybe no one values us enough. Maybe we're worthless. That's why

*Originally translated from the Love & Hope Issue, published December 2023. Full credits and stories in the print issue.

Most popular

.jpg)

Relacionados

.jpg)

Anna Wintour e o presidente da câmara de Milão, Giuseppe Sala, revelam a localização do Vogue World 2026

24 Feb 2026

O que lhe reservam os astros para a semana de 24 de fevereiro a 2 de março

24 Feb 2026