To write them in any other way would be to distort their roots, to temper with their nature. We’ll live them just as they can be found on the modern world’s most global encyclopedia, Google. Egyptian Blue. Azurite. Ultramarine. Cobalt Blue. Cerulean. Prussian Blue. Phthalocyanine Blue. International Klein Blue. These are some of the variants of shades of blue that have already been used, and still are, in the world of art. Many names we know by heart have already used this color as a manifesto and vehicle of expression. These are some of them.

To write them in any other way would be to distort their roots, to temper with their nature. We’ll live them just as they can be found on the modern world’s most global encyclopedia, Google. Egyptian Blue. Azurite. Ultramarine. Cobalt Blue. Cerulean. Prussian Blue. Phthalocyanine Blue. International Klein Blue. These are some of the variants of shades of blue that have already been used, and still are, in the world of art. Many names we know by heart have already used this color as a manifesto and vehicle of expression. These are some of them.

It was bizarre at first. And expensive. So much so, that legend has it that Michelangelo interrupted his painting of The Entombment (1500-1501), commissioned by a church in Rome – and now in exhibition at The National Gallery, in London – because he couldn’t afford to buy more blue paint, in the original shade Ultramarine (in Latin, ultramarinus, which means “beyond the sea”), one of this piece’s predominant colors. A similar situation would have happened to Johannes Vermeer that, as it is said, went into debt in order to have access to the highly requested tone, put into evidence in the beyond-famous Girl With A Pearl Earring (1665). The pigment remained costly up until 1826, the year when a French chemist discovered its synthetic version, later called French Ultramarine. And like that it stayed, forever, as something magical. When referring to its typical Blue (1961), where tiny black dots and a red line cut through the blue that blends in with the sky, Joan Miró stated that “the spectacle of the sky overwhelms me”. That transcendence was what he aimed to achieve through that line of work, where it is suspected to exist a dream state that points over to a starry night. But let’s rewind. Because, as it seems, the first time the color blue was “actually” produced dates back to 2200 b.C., to the old Egypt, in attempt to create a tint that could be applied to numerous surfaces. They did it using a semiprecious stone, lapis lazuli, a mineral that together with gold was used to paint over and decorate the tombs of pharaohs. Its offer, however, was slim, and it made it necessary to find a new way to “fabricate” this blue. This came to happen through the (heated) mixture of limestone, sand, coper and calcium under temperatures surrounding 17 degrees Celsius. The result is a slightly turquoise blue, richly saturated, we now know as Egyptian Blue or, if we’re being precise, cuprorivaite.

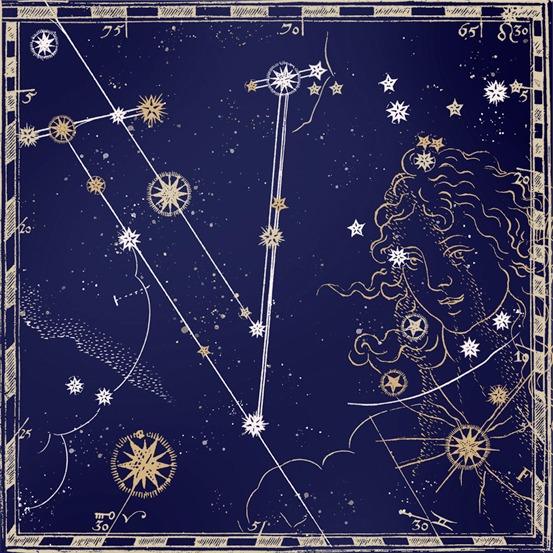

Fast-forward to the period between 1526 and 1528, when Hans Holbein, the Younger, painted the Portrait of a Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling using, as a backdrop, Azurite, a deep “imperfect” blue derived from the mineral with that same name. Around that time blue already was, in its still limited variations, the most coveted color in Europe – where it had spread a few centuries prior – with a price tag rivaling the one of gold. It is commonly mistaken, by common mortals, for the (way more luminous) shade Cobalt Blue, discovered during the VIII and IX centuries, where it was used, majorly, for ceramics and jewelry – this is the tone found in Chinese china, for example. It would only be in 1802, when a scientist invented a purer version of the compound, that its commercial production began. Wanted by all, this blue was used by many artists, such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who recurrently painted with it, as he did in The Parisian (1874), where many shades are combined in a nearly perfect renaissance orgy, or Vincent van Gogh, who took advantage of the shade in order to create the masterpiece that is The Starry Night (1889). In another Pantone spectrum we find Claude Monet and his melancholy, ideal for the placid Cerulean Blue (that in its derivation from the Latin, caelum, means “sky”), a tone that exudes calm and tranquility. A good example of that peace is Impression, Sunrise (1972) or some of the paintings making for his long series of Water Lilies (1914-1926). We won’t overanalyze every nuance involving the color blue in art, it would be simply impossible, especially considering that the most important one is coming, and all of us, even those outside the threshold of the subject, know it had to be Picasso’s Blue Period. Though a parenthesis to the Phthalocyanine Blue shouldn’t be ignored, and despite its hard pronunciation, it is easily identifiable: it’s the Barnett Newman blue, the one of Wassily Kandinsky and of Roy Lichtenstein, whose unforgettable Moonscape (1965) leaves no shred of doubt about the relevance, and magnificence, of that blue that floods our eyes. So much so, that Mark Rothko took many of its cadences to build one of his most beautiful, and unexpected, paintings, No. 61 (Rust and Blue), dating back to 1953, and currently for exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, in Los Angeles.

Let the drums roll, then. The Blue Period of Pablo Picasso fits between the 1900 and 1904 timeframe, during which, according to the web page dedicated to the artist – but with no connection to his descendants – he produced “-US">essentially monochromatic paintings-US"> in -US">shades-US"> of -US">-US">blue-US"> and -US">-US">blue-green, only occasionally warmed by other colors." The exact reason why the painter made this decision is unclear (if there even was a conscious decision), but it is suspected that Picasso had felt some motivation due to the suicide of his friend Carlos Casagemas, a Spanish poet that killed himself at the Café L’Hippodrome, in Paris, on the 17th of February 1901. At that time, the painter had only 19 years old and lived on and off between Barcelona and the city of light. “IIt was thinking about Casagemas that got me started painting in -US">-US">blue”, he confessed years later to his biographer, Pierre Daix, as the highly regarded website Artsy explains. “One of the first he produced, The Death of Casagemas (1901), responded directly to Casagemas’s suicide. The oil-on-wood work shows the poet’s bluish-green face swaddled in white blankets. He looks almost peaceful, as if sleeping, but Picasso’s addition of a bullet hole on his subject’s temple lays the tragedy bare.” According to Artsy, the usage of -US">-US">blue to communicate “pain and desolation” can also come from the influence of painters of the Symbolism, such as Paul Gauguin, “who filled canvases exploring themes like human destiny with -US">-US">blues." And, might we add, the zeitgeist (or spirit of time) that hovered the artistic and intellectual community on that century’s debut. It’s not random that one of the declinations Picasso elected, during those three “-US">-US">blue years”, was precisely the exceptionally deep, and disconcerting, Prussian Blue.

But there’s more. According to the afore-mentioned website, the fact that the “marginals”– prostitutes, beggars, drunks, the outsiders of society, common characters of this time – had become a primary focus of this period of Picasso, also helps to understand some part of his chromatic choice. The painter manifested the solitude and melancholy of his pieces’ protagonists through the nearly exclusive use of blue, something almost unprecedented in the History of Art up to that moment. A good example would be the Portrait of Angel Fernández de Soto (1903). And that’s not all. "In works like Mother and Child by a Fountain (1901) and Buveuse assoupie (Sleeping Drinker) (1902), Picasso focuses on two lonely, abject women. Both were likely inspired by his visits to the Saint Lazare women’s prison, where inmates often suffered from venereal diseases. The bent bodies and blue-gray palette of each subject communicates everyday hardship, but Picasso elevates their plight by swaddling them in cloaks that resemble representations of the Virgin Mary." From all the paintings of this Blue Period, the most significative might be, according to the experts, Life (1903), which transports us to an artist’s studio. "While earlier versions of the painting, locked beneath the final work and revealed by X-rays, show Picasso as the central figure, in the end he depicted Casagemas as his subject. He is naked except for a loincloth as a nude woman clutches him, and the two look over at a mother and child. Behind them sit two canvases covered with crouching bodies. Every element of the scene conveys vulnerability. The artist brings different facets of his troubles into a single canvas: poverty, dejection, creative anguish, and grief for those lost, like Casagemas", Artsy clarifies. Maybe this was his way of expelling the pain, since immediately after this (rather long) Blue Period of Picasso, the painter moved definitely to Paris and was reborn under the most joyous, and all encompassing, pink palette.

If this Blue Period holds as the most relevant in all of Art’s History, then there is no escaping the mood that took over Henri Matisse when he completed his four-lithography series, Blue Nudes, in 1952, made from scraps and cuts showing naked figures in various positions. The color of choice? Classic Blue, the same blue declination the Pantone Institute elected for 2020. And what to say about “our Helena Almeida”, that splashed her two pieces with a restless blue, somewhere in between this classic we now see resurrected and the coveted International Klein Blue – as seen in the piece For Study For Inner Improvement (1977), that seems to swallow the tone patented by the famous French painter? Almeida was a master in the practice of the trilogy black, white and blue, and will forever stay engraved in the retina or all lovers of art by the way she manipulated shadows, absences and the direct relation to the spectator. Is it a coincidence then, that she took advantage of the color “invented” by Klein? Probably not. “What is blue?”, asked the pioneer of the New Realism. “Blue is the invisible becoming visible. Blue has no dimension, it is beyond the dimensions other colors are a part of”, he concluded. Born in April 1928, Yves made blue his fetish color, and the search for the perfect blue became, in a way, his life. As Stella Paul explains in the book Chromaphilia: The Story of Colour in Art (2017) “In Klein’s case, the means were crucial to the message, and his means were the ultramarine blue, as similar as it is different to the color that echoed in medieval and renaissance art.” Only that the pigment used to produce the famous Ultramarine was too “incandescent” for the painter, and it ended up darkening, taking back from the luminosity he so deeply searched for. Klein worked with a Parisian paint salesman in order to create chemicals that would interfere with the process, and “the result was a synthetic agglutinant called Rhodopas M60A, that can be diluted within various levels of viscosity with ethanol and ethyl acetate. Klein ordered his own synthetic customized paint using this new agglutinant, that he then patented as ikb (International Klein Blue)”. From 1957 onwards, that alone, was the pigment he would use, going into his blue season, “a transcendent vision of the infinitude of space and dreams.” Untitled Anthropometry (ANT 110), of 1960 or Blue Monochrome (1961), owe their magic to this blue. Inspired by the French philosopher and poet Gaston Bachelard, he would have explained: “First there is nothing, then a depth of nothing, then a depth of blue.”

Originally published on Vogue Portugal October 2020 issue, Into The Blue.

Most popular

Relacionados