In the long history of fashion, many have stood out. But even among these, there is a sublime species that advances beyond the banal, achieving something rare: the revolution of this art form and industry.

In the long history of fashion, many have stood out. But even among these, there is a sublime species that advances beyond the banal, achieving something rare: the revolution of this art form and industry.

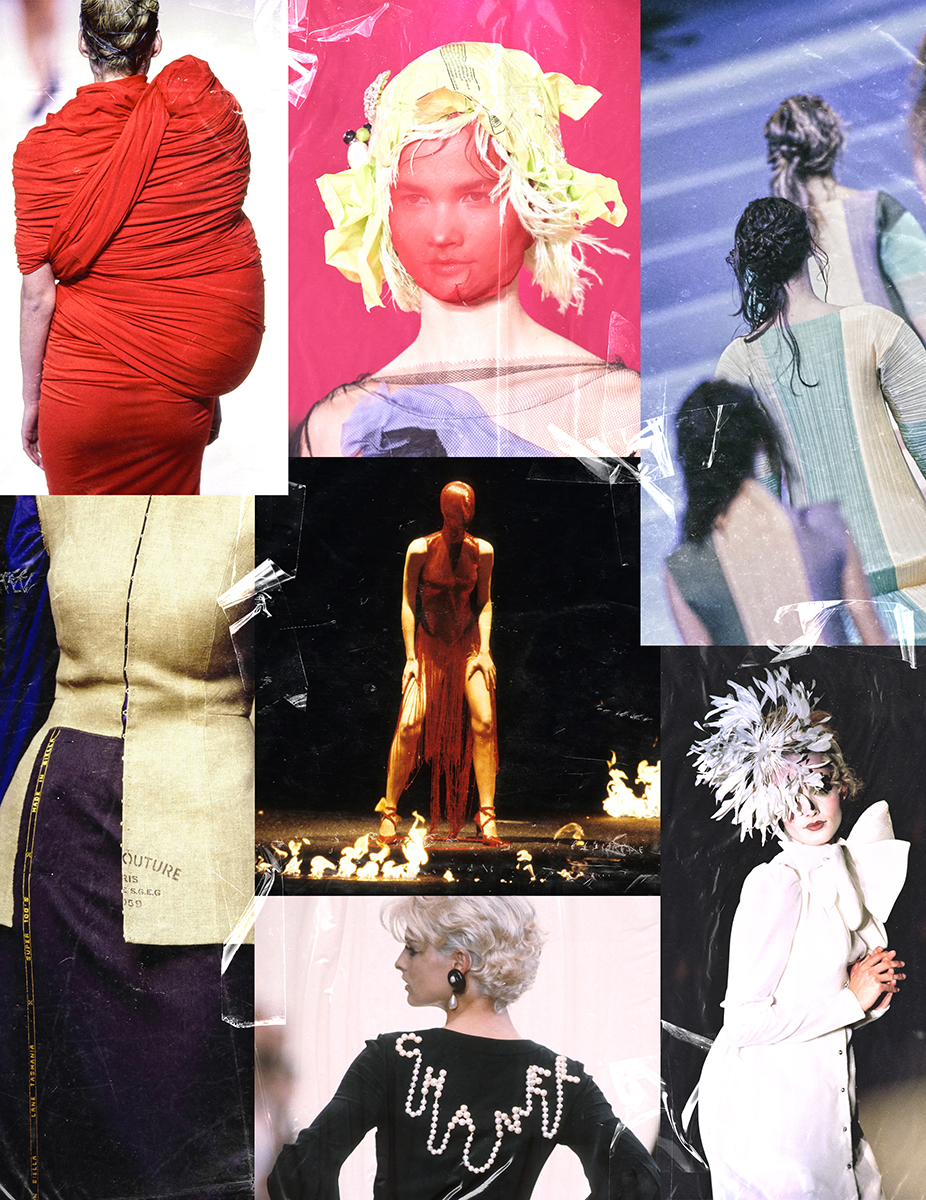

We all have our heroes, those we idolize for the way they escape the banality of the rest of humanity - they are the few who manage to go beyond the canon of the human and swing on the edge of the divine. If some of us reserve this status for fictional characters, Fashion lovers replace comic books with the pages of the history of this art form. Our adoration confines to the fashion show archives, scandalous tell-alls, and obscure videos where we find the names that revolutionized the industry we love so much. These are the ones who, among thousands of creators who pass through the revolving doors of Fashion, have changed how we understand it. Whether by the nature of the clothes they made, the ability to express the cultural and social atmosphere to which they belonged, the innovation they imprinted in their pieces, or the way they rebelled against the status quo - these are the revolutionaries of Fashion.

As a true lover of Fashion History, there is a latent desire to introduce the names responsible for the establishment of this artistic expression. Perhaps it would be appropriate to document those who took it upon themselves to bring the ancient notions of clothing closer to what we understand as Fashion. Names like Charles Frederick Worth would mandatory for such a task, the man responsible for the birth of what we currently identify as Haute Couture. Although it is tempting to enter the French courts of the 19th century, our purpose is not simply to recreate a school book. We jump painfully ahead of names like Worth or the Callot sisters, but we strongly recommend the research necessary to achieve literacy in Fashion History. We move full steam ahead to the first decade of the 20th century, where we meet Paul Poiret, a name known to the most obsessed Fashion lovers, yet anonymous to the general audience. An introduction is required: Poiret was a Parisian designer who established the current canon of the Fashion industry. The French craftsman learned his trade from some of the most highly reputed couturiers of his time, carefully developing the rules for the manufacture of garments. But throughout his extensive career, Poiret was busy destroying, subverting, and ultimately revolutionizing the Fashion game: starting with the liberation of women's bodies. At the tender age of twenty-four, Poiret dared to break the need for a petticoat and a corset in women's clothing. The Parisian proposed a rupture of the silhouette that had hitherto been the norm: an absurdly exaggerated female body shape, where both breasts and bottoms were artificially projected outward from the body. By loosening women from their rigid garments, Poiret dissolved the hyperbole of their silhouette. The modernity proposed by the designer implied the valorization of new techniques. If, until then, tailoring was the main focus of women's clothing, as it was for men, the Frenchman introduced the importance of other details, such as drapery. Inspired by the traditional clothing of Greece, Japan, North Africa, and the Middle East, Poiret created a new standard for Western fashion. Although he was not the only one to incite a change of paradigms, the designer understood early on what would become one of the great laws of the industry he helped create: advertising matters. With an affinity for personal promotion, Poiret assumed himself as the creator of a new (and revolutionary) silhouette, the world believed.

If Poiret may be a name that, for most people, is unknown, we move on to one that everyone recognizes. Coco Chanel is a name that has incredible resonance, obliterating any language and cultural barriers. In popular culture, the designer is one of the titans of Fashion, the founder of the Maison that has become synonymous with luxury. But Gabrielle "Coco" Chanel is much more than the logo through which tens of thousands of euros worth of purses get sold. With a life story almost as admirable as her talent, the couturier grew up in an orphanage in the French countryside, gradually conquering the world. Chanel was not content to captivate the world. She had to revolutionize it. The French designer is credited with popularizing pants in women's closets. Her creations diverged from the norm in one essential aspect: they didn't aim to extol beauty but to promote freedom of movement, which was only possible through comfort. Inspiring herself in men's fashion, Coco Chanel created an androgynous aesthetic language: pants, pockets, and tweed, exclusively associated with men, were now reinterpreted through a feminine sensibility. Similarly, she popularized matching sets for women: a formal jacket with a straight skirt. Like Poiret before her, Chanel did not "invent" the revolution associated with her name. As significant as her contributions are, she was not singularly responsible for women's liberation — what she did do was foresee the winds of change that were rapidly spreading. The revolution incited by Chanel was more profound than the pants she produced, having set a new standard in the Fashion industry: it is not enough to listen to what the customer wants, you have to predict it. Her greatest talent was not in design or cutting but in anticipating and responding to impending social changes. Ironically, the instinct that ensured her success would also end up being the cause of her downfall. Aiming to ally herself with what she thought was the winning side, Chanel erred in her choice of alliances during World War II and tarnished her name forever by associating herself with a Nazi general.

Many are stories of rivalry in the Fashion world. The industry is the perfect habitat for inflated egos. Coco Chanel never found a rival like Elsa Schiaparelli, a designer with antagonistic artistic ambitions and visions, whom the Frenchwoman pettishly titled "the Italian artist who makes clothes." The rivalry between the two, which culminated in a ball where Chanel burned her competition's dress, is something beyond the scope of this text. Once again, research is encouraged. Although they were mortal enemies, both influenced the Fashion industry irrevocably, even if in completely different ways. If Chanel sought to adapt her clothes to the changes in women's daily lives, Schiaparelli created pieces that were visible manifestations of her imagination. Surrounding herself with some of the most influential names in the art scene of the first half of the 20th century, the Italian designer created wearable art. It was the introduction of this concept that revolutionized the world of Fashion. No person before Schiaparelli merged the lines between art and Fashion so effectively. Through collaborations with people such as Salvador Dalí, the couturier created a unique aesthetic language that would often be referenced by the Fashion industry of the future. Her application of Surrealism to Fashion contributed to creating pieces like the skeleton dress. In addition to an artistic depth, Schiaparelli introduced a sense of humor into women's closets. A hat in the shape of a shoe wasn’t meant to be elegant or practical but humorous. If her design is the characteristic she stands out for, the couturier changed the industry in ways unknown to many. Schiaparelli was the first to popularize the use of zipper closures, plastic pieces, and even the wrap dress.

Like Schiaparelli, who put shoes on atop her head just for fun, Fashion has never respectfully valued footwear. Throughout the dramatic narrative of the female closet, shoes have never been more than mere accessories, used as a support for clothes. But shoes are true works of engineering, carefully orchestrated by unknowing craftsmen. The first to stand out among the haze of his peers was Salvatore Ferragamo at the beginning of the 20th century. The Italian shoemaker was the first to gain global recognition, breaking all the stigma associated with the profession. His impact is such that the world of shoemaking is divided into before and after Ferragamo. In his autobiography, the designer confessed, "I was born to be a shoemaker." Dedication to this art was omnipresent in his life. At ten, the young Italian produced shoes from scratch for his sisters. Ferragamo rose to unimaginable heights from his family home in a poor village in rural Italy. Wedge shoes, round-toed shoes, Roman sandals, stilettos. The shoemaker invented them all. His success came not only through his inventions but also through his attention to comfort - the creator studied anatomy. Salvatore Ferragamo revolutionized Fashion with the sheer force of his creativity and created the lexicon of modern shoe-making.

Wasting no time, we return to the realm of clothing. And this time with three inseparable names of the modern Fashion industry. Cristóbal Balenciaga, Christian Dior, and Yves Saint Laurent. Cristóbal Balenciaga radically innovated Fashion with his silhouettes and his talent for cutting, like Paul Poiret. The Spaniard possessed the rare ability to combine tailoring and draperies seamlessly. The designer was known for his precision and perfectionism. Beyond the luxurious materials he insisted on working with, the couturier paid attention to detail in a way that verged on the pathological. Occupied with the tiniest details, Balenciaga created collars that moved away from the collarbone to elongate the neck or slightly indented sleeves to show the jewelry on the wrists. With the elegance of his customers in mind, the designer created a series of new silhouettes, such as the universally flattering babydoll dress. His disciple, Christian Dior, also rose to worldwide stardom through means of a silhouette: the New Look debuted in his first Haute Couture collection in 1947. The post-war world needed the innovation that Dior brought to fashion. The assumed femininity of the silhouettes structured by full skirts and corsets was a breath of fresh air. Curiously, the one who coined the term "new look" was the director of Harper's Bazaar, Carmel Snow, who, after the show, pointed out: "It's a revolution, dear Christian! Your dresses are a new look!". The success of Dior's Haute Couture, combined with clever marketing strategies, such as a line of perfumes and accessories, put Paris back on the map as the world’s Fashion capital.

Like his mentor, Yves Saint Laurent sought to revolutionize the repertoire of women's closets. In 1966, the young designer debuted Le Smoking, a men's suit adapted for a woman's body. Interpreted as a symbol of rebellion, Saint Laurent spoke directly to a generation of women ready to revolutionize themselves against the gap between the two genders. Balenciaga, Dior, and Saint Laurent teach us a lesson in adapting, beyond their technical precision and innovation in silhouettes. The first modified the codes of Haute Couture but, unable to yield to its notion of quality, refused to produce a ready-to-wear line. A decision that would lead to the eventual closure of his eponymous label. Christian Dior, on the other hand, was able to adapt, producing lines complementary to his Haute Couture. Only Yves Saint Laurent understood the true potential of a ready-to-wear line, positioning himself at the forefront of the industrial revolution. In the Rive Gauche boutique, the French designer saw an opportunity that would dictate the future of Fashion. Through this new segment, Saint Laurent set a precedent for the great Maisons: ready-to-wear lines that held the prestige associated with luxury.

We can’t discuss the modern Fashion industry without mentioning Karl Lagerfeld. The designer was one of the revolutionaries of the medium. Through his time at Fendi, Chanel, and Chloé, Lagerfeld was the first chameleon creator, able to adapt brand codes to the aesthetic needs of his clients. Logos, currently seen as the commercial anchor of a brand, we're an initiative practically invented by Kaiser, who personified the definition of "creative director." Responsible for the creation of Zucca, Fendi's pattern, as well as Chanel's logo with two intertwined C's, Lagerfeld was a marketing genius. He was the revolution of Chanel, that, by the 1980s, was in a poor state. The designer created a new standard of productivity and energy, leading the brand into the 21st century. Through his adaptive style, Lagerfeld created the role model for the present turnover in the Fashion world: any brand can be revitalized with a new creator. This legacy, visible in cases like Tom Ford's presence at Gucci, influences the current Fashion landscape in an incomprehensibly significant way. The transformation it has brought about is understood in Lagerfeld's philosophy, as he indicated in an interview with Women's Wear Daily: "It doesn't matter who has more talent, the question is who has more influence."

We do not reduce the Fashion revolution to its capitalist ends. Economic growth doesn’t limit the industry’s artistic depth. From the 1980s on, a new kind of revolution begins the modern intellectualization of Fashion. In Paris, Japanese designers like Rei Kawakubo and Issey Miyake revolutionize the aesthetic sensibilities of the West. Unlike the connections of female sensuality that see the body as the core of sexual attraction, East Asian sensibility shifts its center to the spiritual and the intellectual. Issey Miyake sought to merge the notions of Fashion from his home country, Japan, with those from where he would eventually settle, France. The designer focused his career on texture as a way to produce sculptural forms, namely through his famous pleats. On the other hand, Rei Kawakubo, with Comme des Garçons, questioned the connection between the body and the clothes that cover it. As the brand name indicates, the designer starts from a male perspective to achieve an unusual sensuality. If until her appearance in Western fashion fashionable was synonymous with the body, Kawakubo has revolutionized this paradigm. According to the creator, the brain is the epicenter of our style. An idea that has revolutionized the way Fashion is perceived, progressively moving away from accusations of futility. The deconstruction of clothing, essential to the designer's approach, catalyzed consequent revolutions, like the one started by Martin Margiela and his deliberately abstract pieces.

In Milan, Miuccia Prada conducts erudite digressions, revolutionizing the notions of luxury in Fashion. The intellectual nature of her work stems from her references. Rather than merely focusing on aesthetic elements in the search for inspiration, the Italian designer enshrines the political, social, and cultural context as a muse. With a Ph.D. in political science, the heiress to the Prada empire, a leather accessories boutique, sought to instill an intellectual depth in her creations. Her collections, extremely controversial early in her career, aspired to question the aesthetic sensibilities of her clients. What is elegant? Who has the power to decide what is beautiful? What exists beyond the aesthetic? All these questions are asked consecutively by Miuccia Prada in her garments. But beyond her intellectual considerations, the designer revolutionized the industry in another way. Until the mid-1980s, luxury accessories were synonymous with a single material: leather. However, with the introduction of the nylon range of products, Prada redefined notions of luxury in the accessories business and made nylon a surprisingly chic material.

If some choose the intellectual path to affirm their revolution, others take the theatrical one. John Galliano and Alexander McQueen are the enfants terribles of Fashion, the problematic children who, by their attitude, have made the designer a rock star. The two share disturbing similarities. Both were products of London's eccentric nightlife, their exuberance inspired by the city's atmosphere. Their success was meteoric, as was their collapse. Galliano, the older of the two, thought of Fashion as a performance. A depth that at the time (the 90s and early 2000s) was unheard of. His genius is not solely understood in the clothes he produced - usually inspired by a historical moment - but by his way of advancing these concepts. For the couturier, his garments were nothing more than letters on a page from which complex narratives were written. Galliano's theatricality is perceptible in Alexander McQueen but, unlike his predecessor, the Brit had an extraordinary aptitude to create the "shock factor", and was, therefore, able to orchestrate it artistically. So much so that the shows of his eponymous label were not only personally iconic moments, they are part of Fashion History. McQueen's performances revolutionized what Fashion could be: no longer just about clothes, but his visceral vision. Think of his spring/summer 2001 show, where the runway takes the shape of an asylum and from where, eventually, a cube hitherto hanging from the ceiling falls to reveal a naked journalist in a gas mask, surrounded by moths. Both Galliano and McQueen expanded the possibilities of Fashion but their art, when superimposed on the unsustainable pace of the industry, contributed to their inevitable ruin.

We hear the orchestra playing. The music is a sign that urgency should be a priority. But before we say goodbye, we hastily mention the name of Virgil Abloh, the American designer responsible for, in a stroke of genius, merging the prestige of luxury with the coolness of streetwear. This agility was not the product of some chance or divine luck. Abloh had a brilliant mind, capable of rationalizing the industry in which he sought to stand out. His calculation of his allowed him to write a rulebook detailing the formula for his success. We could spend innumerable pages detailing all the designers responsible for the different revolutions of the Fashion industry. But, if that wish was granted, this article would go on forever. Vivienne Westwood, Mary Quant, André Courrèges, Madeleine Vionnet, Paco Rabanne, or Jean Patou. All relevant names to the matters at hand, but that had to be overlooked. For those who think that the absence of any of their names is sinful, understand the difficulty of the task and forgive any oversight. Fashion is a long tapestry where each designer adds a bit of their vision to the legacy of the art form. Any stitch can be the genesis of a pending revolution.

Originally translated from The Revolution Issue, published April 2023.Full stories and credits on the print issue.

Most popular

.jpg)

Relacionados

.jpg)

Anna Wintour e o presidente da câmara de Milão, Giuseppe Sala, revelam a localização do Vogue World 2026

24 Feb 2026

O que lhe reservam os astros para a semana de 24 de fevereiro a 2 de março

24 Feb 2026