What's Next

On social media, sharing has always been the watchword. But a new generation of influencers is reconstructing its original purpose. Why reveal when you can hide?

“Where's that jacket from?” ‘Where did you buy those pants?’ ”What brand is that sweater?” These questions are omnipresent in the vast majority of TikToks that come my way. My FYP (for you page for those less educated in brain rot, the timeline of the Chinese app) is run by my love of fashion. Naturally, I'm inspired by what I see on the small screen that shows me the world. Even though I consider myself fashion savvy, it's amazing how many products I see in front of me that I have no idea where they come from. My ignorance creates in me a need to know - it's from here that I pluck up the courage to ask: “What brand are those shoes?” My questions are rarely answered. At best, I get other users commenting or liking the comment. These little incentives are nothing more than voices as desperate as mine, thirsty for a comment that will satisfy their curiosity. But even though my irritation is latent, I concede that there is something beyond my frustration. Surely these gatekeepers aren't doing it for sadistic pleasure. There must be a reason.

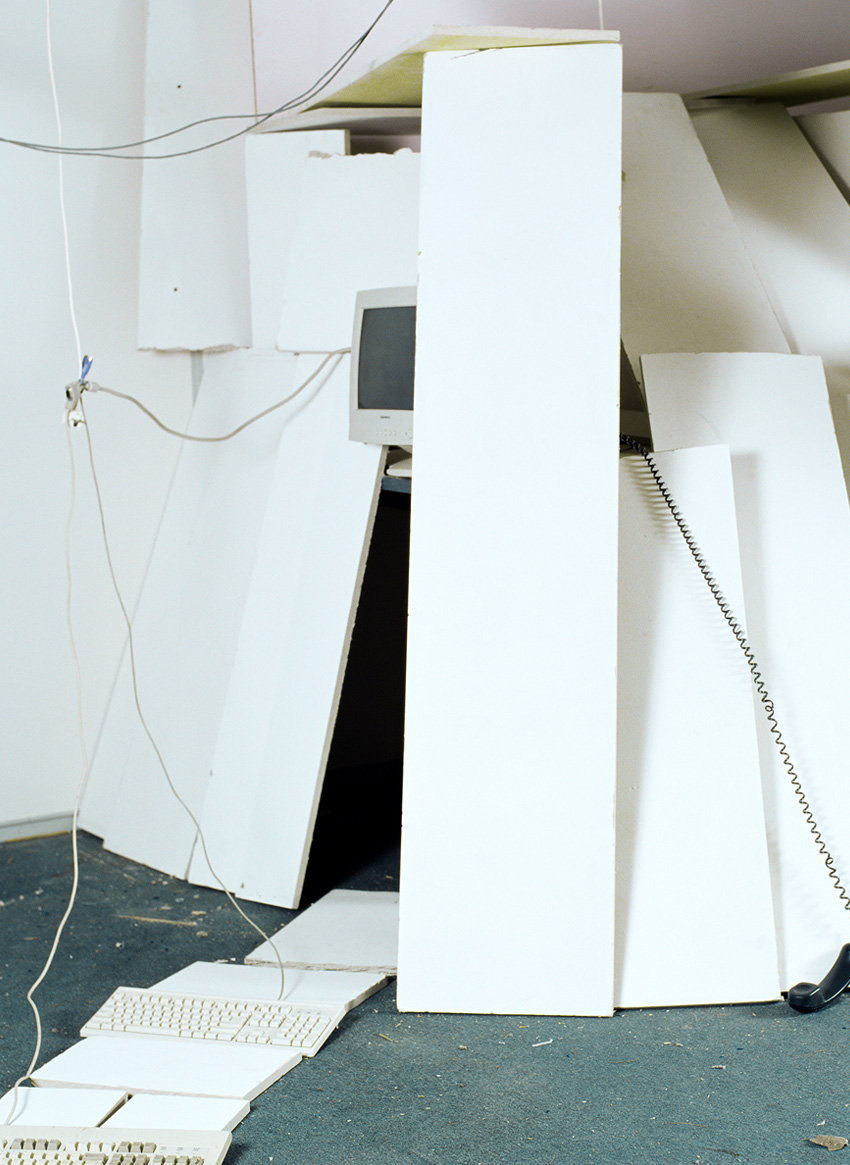

“I don't understand why they keep asking me where the clothes I wear or the accessories I adorn myself with come from.” Letao Chen, a London-based experimental artist and micro-influencer in her spare time, expresses her frustration when we meet for lunch. Known for her video installations, where the irony of online slang is interspersed with virtual spirituality, the artist has seen success on the video platform. From cultural analysis to simple fit checks, Chen has achieved what many covet: she has found her niche. Her artistic spirit is the protagonist of her TikToks. Her most popular videos are clever parodies of the trend of “jane birkinfying” a wallet. For those who aren't chronically online, let me serve as a guide: the online phenomenon is based on the iconic photographs of Jane Birkin with her namesake purse and the way she decorated it - filled to the brim with small objects. The trend, which is based on the instinct to decorate our possessions organically, has reached the point of capitalistic euphoria. Instead of using souvenirs or other personal objects, TikTok users buy them in bulk “in order to decorate suitcases in the least individual way possible.” Chen, in order to compensate for what the trend has become, bought two fake Birkin bags which she decorated in a personal way. The artist used her Chinese descent as a source of inspiration and created extremely personal key rings. What Chen has done is touching. Inspired by her childhood memories, the artist has created a series of objects that she hangs from her purses. “I grew up in a Chinese immigrant household in the United States, in our house, functionality was always prioritized over aesthetics. This was always something I struggled to accept growing up, it was something none of my friends had. My house has speakers hanging in the kitchen with wires in the walls, connected to the computer in the living room. It's functional, but the aesthetic is somewhat artistic. Inspired by this, I created a key ring that is a gua sha, a functional object, used in a purely aesthetic way. In the hole of the gua sha I hung a bracelet that my grandmother gave me and a braid from a wig because my mother used to sell wigs.” Chen explains her process openly, but discusses a hidden frustration. “In the comments of the video in which I explained the object I created, I have people asking me if they can buy them from me. It doesn't make any sense to me, I've just explained how this object is so representative of who I am, and some people's first instinct is to buy it.” The purpose of Chen's TikTok was not to sell a product, but to inspire. “Why, instead of trying to buy something that someone else has made, don't we use similar philosophies to create something?” Chen taught the methodology behind his process, but his audience wasn't willing to learn. “I think the beauty of these objects is that they're personal. It would be so nice if we could understand that you can't buy your identity, you make it.”

The subject of gatekeeping is far more complex than the simplicity of a key ring might indicate. Letao's issue, as well as that of a growing online community, is that we have commodified originality. The trend of adding charms to wallets, popularized by brands such as Miu Miu or Balenciaga, is proposed as the ultimate sign of cultural decadence. With discourses covering everything from academic literature to reality TV, the phenomenon of key rings being bought is considered a sign of the state of capitalism in which we find ourselves. These voices are convincing. A keyring is, in a way, the most genuine representation of originality. They are made up of little charms we collect on our travels, gifts from friends, trinkets we find on the street - insignificant objects that hide stories that define who we are, who we hang out with and where we go. By buying an intentionally random keyring that is mass-produced, we empty it of any meaning it might have. The need to buy and sell replaces the small, delicate humanity that these objects represented. Letao makes this object the subject of an entire manifesto. And, although she hesitates to call herself an influencer, what she describes is a category of influencers who deny their original purpose as glorified salespeople.

Please forgive the ensuing rant but after listening to Letao, the concept of influencer in its current form is progressively difficult to accept. We ask the courtesy of understanding that, at its core, the issue isn't about any specific person, but about the abstract concept of a profession that atrophies the way we socialize in order to sell us products we rarely need. Our minds, still so stuck in their animal condition, are incapable of recognizing that the people we see on our small screens are not our friends. The brains of social animals, preconditioned to form interpersonal bonds, are incapable of understanding that the people who are with us on the way to work, in waiting rooms and even in bed, don't share real intimacy. That's the genius of influencers. Taking advantage of the familiarity and trust that peer-to-peer relationships invite, these people “recommend” products - read: sell us everything they can. This is, admittedly, a rather skeptical view of the issue, but after talking to Letao, it's hard not to feel radicalized.

What influencers like Letao propose is, in this sense, quite refreshing. Refusing to promote any one brand, these are people who choose to think about their social media presence differently. Whether it's a mere hobby, a form of artistic expression or a creative outlet, a new generation of influencers is seeking to loosen the commercial grip of social media. Call them gatekeepers if you must, they don't mind. It's important to note that most of the influencers I observe have a relatively small network of influence. Nothing tells us that if (or when) their audience grows - also increasing the possibility of income for product promotion - they won't turn their backs on them. Even Letao, with all the fervor of her arguments, agreed to promote a brand after it sent him a pair of wallets. Not that this invalidates what she told us, but it puts her opinion into context - when faced with the temptation of monetization, few remain tightly bound to their previous ideas.

Of course, there is a side to gatekeeping that has less to do with such esoteric and intellectual values and more to do with adolescent pettiness - arguments of “If I publish, everyone will copy me.” It's hard to admit that this kind of thinking occupies the minds of some adults, but some have nothing else to do. Although she would like to be able to put this kind of attitude down to a teenage mentality, Moira Gonzalez, visual communications director at Charles Jeffrey Loverboy and self-proclaimed vibes curator, thinks of gatekeeping differently. “I've had several situations where I've shared my ideas or my opinion on certain things and they've 'stolen' the idea from me before I could execute it.” What Gonzalez describes is a fear specific to a generation that knows how easily ideas are usurped. “With my friends I'm always honest and open about what I like or where I find inspiration, but if we're talking about strangers, or online, then it's something I actively choose not to share.” The sentiment is echoed by many online. In an age where an outfit is monetizable, sharing the information of how you achieved it can be a waste of money. “I think it's all part of a need to protect ourselves,” adds Gonzalez. “It's not meant to be malicious, it's just something I do because I know that if I see potential in something, I want to be the one to receive the benefits.” What Gonzalez and Chen report is not far off. Neither of them denies or resents the inspiration they can serve others - that's what they want to provoke in the people who watch them. The mentality promoted by TikTok that a personal sense of style is not built, but bought, is annoying. Chen sums up his philosophy impeccably. “I want what I do to inspire others to do the same, but if they copy me, I think we all lose.”

Originally published in Vogue Portugal's What's Next Issue, from December 2024. Full credits and stories in the print issue.

Most popular

.jpg)

Relacionados

.jpg)

Anna Wintour e o presidente da câmara de Milão, Giuseppe Sala, revelam a localização do Vogue World 2026

24 Feb 2026

O que lhe reservam os astros para a semana de 24 de fevereiro a 2 de março

24 Feb 2026