Fashion’s history is also written by small inventions. Small inventions in size, but huge revolutions in the lives of each and every one of us. And for the record: many of the items presented here are some of those cases where size, really, doesn’t matter. You’ve got to read it to believe it.

Fashion’s history is also written by small inventions. Small inventions in size, but huge revolutions in the lives of each and every one of us. And for the record: many of the items presented here are some of those cases where size, really, doesn’t matter. You’ve got to read it to believe it.

Soutien

One of the soutien discovered by Beatrix Nutz, investigator in the Innsbruck University.

The arrival of the first bra, officially, dates back to the year 1914. It was born, like many other good ideas, out of something greater. Mary Phelps Jacob, an American woman tire of the bothersome corsets, decided to tie two silk scarfs with pink ribbon and a string. Phelps patented the idea and became forever known as the great creator of the piece. However, in 2021, Beatrix Nutz, an investigator of the Archeology Department at the University of Innsbruck, Austria, came around to proving that people have been wearing bras for over 600 years. In the archeological investigation, four bras were discovered, locked inside a safe, dating back to the XV century. But, in this story, not everything is pink. At the end of the 60s, around 400 activist women belonging to the Women’s Liberation Movement came together in protest against the contest Miss America, in Atlantic City, USA. The election of the most beautiful American woman was seen as arbitrary and oppressive to the beauty of women everywhere due to its commercial exploitation. An episode that became forever known as Bra Burning. Three decades later, bras came back stronger (and more sustained), thanks to the top model Eva Herzigova and her memorable campaign, “Hello Boys”, for Wonderbra, to which she lent her face and body. Nowadays, bras, even if still relevant, don’t find themselves in the spotlight as much as they once did. Let alone because of the pandemic, that has turned them into something residual. It was because of it, that many women understood that their lives were much lighter without that particular piece of lingerie – and thus they became more themselves, freer and looser.

Bra Hook

Corset from the beginning of the 20th century, where several bra hooks are visible.

Without hooks there would be no bras – at least it wouldn’t have been made so easy, for those who (still) wear it, to do so. Do you even know what bra hooks are? In a simplified definition, they are those little metal pieces, in the shape of a hook, where one side is male and the other is female (since they fit into one another), that do the job of tightening the bra. Now let’s move on to their invention. Let’s talk about Mark Twain. And the reader will be asking: what does literature have to do with the pants – in this case, with bras? Everything. Born on the 30th of November 1835, in Florida, USA, Mark Twain, literally pseudonym which immortalized the writer and critic, was also the inventor of many patents that to this day carry his name. The author of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer was, prepare to be amazed, responsible for the creation of bra hooks, as we know them today. Mark Twain patented an improvement of the previously existing bracket, in 1871. By naming his invention an “improvement on the adjustable and removable straps for clothing”, Twain didn’t mention the feminine inner garments on his patent request (# 121.992), referencing instead, “corsets, pants or any other garment where my strap can be used”. The hook is still used today, in bras, but not only. It is also proof that even the craziest of ideas – or those coming from the unlikeliest of minds – are, more times than one, the best.

Zippers

Photograph from the 1960s, where the model shows how to handle a zipper.

It is often said that the best inventions take time to come to fruition. And the zipper is a perfect example of that belief. The beginning of its path goes back to 1851 when the North American Elias Howe became famous for inventing the sewing machine. Focused on the success of his creation, he didn’t pay too much attention to the patent of an “automatic and continuous closing system for clothing”. Half a century later, the Russian Max Wolff design a different type of zipper which also ended up no being commercialized, since it was considered too advanced for its time. It is Whitcomb Judson, a mechanical engineer, to whom we usually give credit for the invention of the zipper. Judson had a closing automatic system, the “Clasp Locker”, which had been very well received by the Chicago Universal Exhibition of 1893. Together with his partner, Lewis Walker, he created the Universal Fastener Company (now, Talon Zipper), in the United States. The enterprise was a success, though sales not so much since the zippers were too expensive. After some necessary alterations in production, it is on the 20th of March 1917 that the final patent is registered. Then followed the overture of another factory in Canada and the invention of a machine that could produce 100 meters of zippers a day. In the 30s, the metallic material was substituted by plastic, making the item more malleable, practical, and desirable. And how would one use the zipper? You’d zip’er up or zip’er down – hence the name.

Buttons

Wool coat designed by maison Dejac, 1973.

Buttons from a Chanel suit worn by Princess Diana.

No one knows for sure when buttons came to be. There are some indications that in remote times, 3000 B.C., they already existed in the Indo Valley, in Southeast Asia. There are also records of their presence in Roma and Ancient Greece. The pre-historical button, let’s call it, was made with objects that had a hole in their center that could do the job. However, the trend didn’t take off and buttons remained pre-historical for centuries. When it evolved, though, they demanded tremendous skill to do develop and, besides that, the raw materials were expensive – having many buttons in a garment was a sign of ostentation, thus they rapidly became an object of desire; they were made with gold, silver or precious stones and would usually be found in cuffs. Around 1760, when the Industrial Revolution had its boom, buttons lost their royal aura, as they became easier to produce. In 1807, the Danish Bertel Sanders revolutionized the history of buttons, by managing to unite two metal discs and hold the fabric. This way, the value of buttons sunk, and the piece was forever democratized. Today, buttons are a part of everyone’s wardrobe, and we don’t even question their existence – who would have thought that such a small object had had such a long and tortuous path.

Lycra

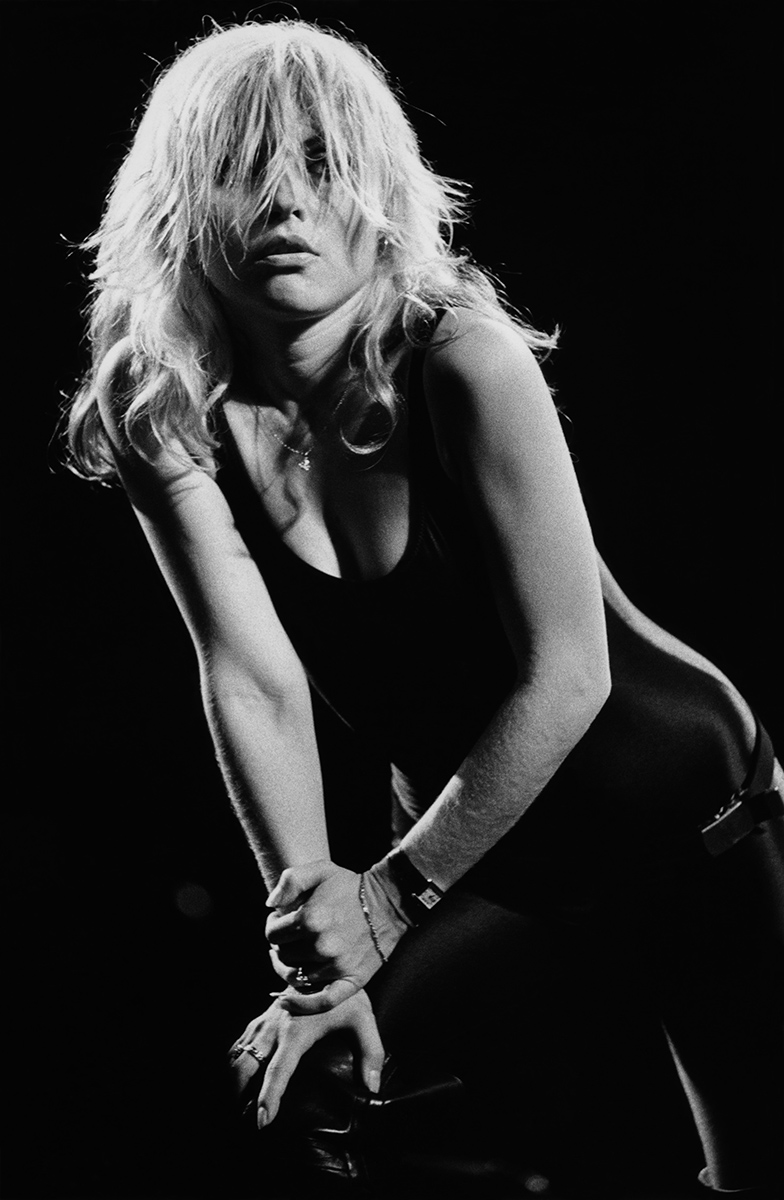

Debbie Harry in a spandex jumpsuit during a concert in Hollywood, 1979.

Christie Brinkley in a lycra bodysuit in the 80s.

Do a quick visualization exercise and try to picture yourself wearing a full nylon bikini. Was that hard? Sure, it was. Today, from bikinis to lingerie, from leggings to sportswear, amongst a plethora of pieces, all of them carry in their composition a thread that, 50 years ago, revolutionized Fashion: lycra. That elastic and resistant synthetic fiber became a synonym of elastane, the generic name of the fiber that created the product. At the end of the 50s, when it was born, the material was used only for lingerie and socks. Then, it substituted rubber, which was being used for elasticity in some pieces of clothing. More resistant and long-lasting than rubber, lycra proved to be a third lighter, besides being more elastic, with the capacity to stretch up to seven times over and return to its original form without losing its shape. In the 80s, with the hysteria around having a fit body and with the popularization of sports, fashion began to bet more and more on skin-tight clothing. Another segment that helped to popularize the material were that decade’s rock bands, who wore the tightest leggings, made from a fabric that had lycra, also known later as spandex. Throughout time, new technologies were incorporated in the fiber until even jeans ended up surrendering to lycra. It’s a type of comfort that remains unseen, but that is always felt by those who wear it.

5 pocket jeans

You can even use it to store coins, a lighter, condoms (who has never?) and “scraps” of things we pick up during the day, but that is not what Levi Strauss had in mind when he added that compartment to his already famous jeans. Yes, we’re talking about that tiny, minuscule, almost invisible extra pocket – but as relevant as any other element in the history of Fashion – situated above the front pocket of the 5 pocket jeans and that had its origin in a common need that cowboys from the XIX century had since they all wore a then very popular timepiece: a pocket watch. Up until when jeans came into the picture, cowboys kept their watch on their vests, but those pockets were unreliable, and the glass would often break. To avoid that from happening, Levi’s started sewing that little detail onto their jeans. This way, they managed to do what we like to call “killing two birds with one stone”: the new pocket assured that the watch didn’t fall; and checking the time became a much more practical and quick gesture. Over time, this minuscule and overall disregarded pocket also began to store whatever people wanted it to, and today no one can conceive a pair of jeans without it. Let’s say that this little compartment, due to the urgency of its functions, is yet another proof that, after all, size doesn’t matter.

Cargo Pockets

Isabel Marant spring/summer 2019 included several models wearing cargo pants.

Givenchy spring/summer 2019 also included several models wearing cargo pants.

From jeans mini pockets we’ll move along to the giant cargo pockets. So big that, in July 2020, the American GQ referred to them as “big enough to fit a MacBook Air”. But that wasn’t always what they were intended for. The British were the first to introduce the cargo pocket by adopting, in 1938, a uniform that was practical and revolutionary named “battledress”. The pants came with a big pocket, placed at the front, that was designed to hold maps, and a top-right pocket that inside had a first-aid kit. The novelty was presented to the United States by Major William P. Yarborough, commander of the 82nd Aero Transportation Division. Unsatisfied with the skydiver jumpsuit, he decided to create a more functional uniform. He then developed the special jumping boots, as well as a uniform that had extravagant pockets on its top and bottom parts. Looking at the utility of the jumpsuit, the army launched a new uniform, in 1943, for the rest of their troops, which included the cargo pants with those two same pockets placed on the side. Those pockets were discontinued after a few years and replaced by frontal pockets, though they would be reintroduced in the 60s, when Yarborough (at the time, a lieutenant), redesigned the military uniform for the Vietnam conflict. As the street style photographic pioneer Bill Cunningham would say: “Fashion is the armor to survive the reality of everyday life.”

Wig

Portrait of Marie-Antoinette (1755-1793).

Ever since primordial times, Fashion has been dictated by elites that want to differentiate themselves from the rest. Such goal was no different in XVIII century’s Europe: by wearing wigs, the aristocracy dictated the rules of an image that symbolized wealth and superiority. The trend began with Louis XIV, the Sun King, who during his reign wore a wig out of necessity – he had started to go bald ever since childhood. From that moment on, wearing wigs was a synonym of status, prestige and social elevation. After marriage, noble young ladies should wear wigs until the day they died. And some even went as far as commanding that, in case they were to die before their husbands, that they were laid in their caskets with their wigs. In order to convey an even higher image, it was common to spread flour or talk powder over the wigs to imitate the look of grey hairs. Another reason why the use of wigs was so widespread was syphilis. One of the symptoms of that epidemic was hair loss. Thus, fake hair could be used to hide the first stages of the disease, easing the shame of going through it as a noble person. The trend lasted until the French Revolution in 1789, where aristocratic heads rolled on the guillotine instead. After that, it fell from grace. Today it is, above all else, an accessory, which can be both ludic, appealing to individual transformation “just because”, or it can reveal itself as a powerful ally in the self-confidence of all those who, because of chemotherapy and other treatments, have lost their hair.

Translated from the original article of Vogue Portugal's Creativity issue, published in March 2021.

Most popular

.jpg)

Relacionados

.jpg)

Anna Wintour e o presidente da câmara de Milão, Giuseppe Sala, revelam a localização do Vogue World 2026

24 Feb 2026

O que lhe reservam os astros para a semana de 24 de fevereiro a 2 de março

24 Feb 2026