Arts Issue

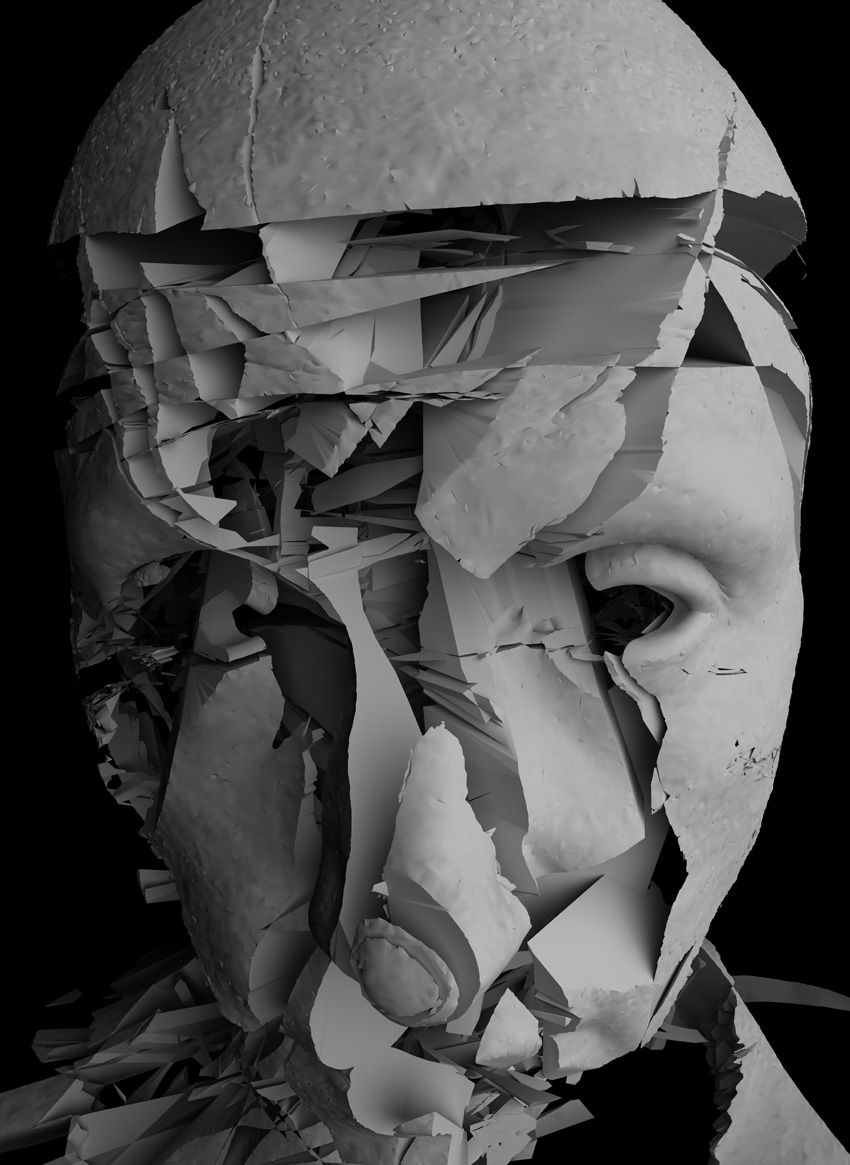

Art and the artist, figuratively linked to each other by an umbilical cord, can be separated. At the same time, they are inseparable. Everything depends on the artist, the work, and the viewer, listener, reader, or appreciator. Everything depends on a combination of factors. All of this is inconclusive - but it's worth giving it some thought.

Listen to a record, read a book, watch a movie, look at a sculpture or a painting; contemplate for a while, but don't let your feelings get mixed up with the sensations. Season it with reason, prevailing morals, public opinion, and, if possible, a judicial indictment, even if it didn't result in an indictment or a sentence - it doesn't matter. Let it rest. In a separate container, enjoy the comments from the cancellation culture. Add a few deciliters of crocodile tears and mix vigorously until it forms an indistinct, consistent paste. Take to the cold heart and leave to cool until the mixture becomes pasty and sticky like chewing gum spat out onto the floor that sticks to the sole of a shoe. Take the bucket back to where you originally intended to bleed the artist's art, but where, with clumsy hands and head, you let ethics and aesthetics, essence, and conduct fall like bloody guts. Pour the contents of the bucket into a one-two-three blender, press the button, and now, yes, do one-two-three and take a deep breath. Phew, not long now. In the end, mix all the parts and preparations from all the containers into a gigantic stomach and put it in the oven, where it will all turn to ash. Bear in mind that this is your stomach. Et voilà! Separating the art from the artist: here's a topic that, just by being evoked, raises more than one question and possibly ignites more than one position. Is it wise to separate the art from the artist? Is it even possible? Is it fair to mix the artist with his art? Is it really necessary to do so? Does a work lose value if we know that its author is worthless? There is also a question that possibly precedes all of these and could be formulated more or less like this: but where does this idea even come from? What makes us think about whether or not we should separate art from the artist? What brought us here?

It seems unrelated, but in a way it is: Bill Hicks (1961-1994), an American comedian who used social criticism as the fuel for his creations in the late 80s and early 90s, is the author of a passage (small aside: the phrase can be heard on Tool's album, Aenima, in the opening of the track Third Eye, which alludes to the use of hallucinogens to reach alternative levels of consciousness and perception of reality) in which he discusses the use of drugs by creative artists. This was at a time when there was an unprecedented campaign against drugs in the United States. Hicks said, "You see, I think drugs have done some good things for us. I do. And if you don't believe drugs have done good things for us, do me a favor. Go home tonight. Take all your albums, all your tapes, and all your CDs and burn them." According to Bill Hicks, this would be the only reasonable and coherent attitude for anti-drug Puritans, because "the musicians that made all that great music that's enhanced your lives throughout the years were real fucking high on drugs." And he even gives an example: "The Beatles were so fucking high they let Ringo sing a few tunes."

The use of this passage to illustrate the divisive theme is justified: art and artists are also mixed up in it. Hicks was stretching the limits of exaggeration, elevating the puritanical pursuit of drugs to a level close to the ridiculous, exposing, on the one hand, certain social hypocrisy when it comes to the consumption of narcotic substances, but also mixing, on the other, the activity of artists and their works with what was their personal and private lives - and we know that these strands are, in many cases, inseparable. The question that needs to be asked, and which could have been addressed to the comedian himself if he hadn't died almost 30 years ago, is: to what extent and in what way am I, as a listener, reader, or viewer, affected by the vices or preferences, flaws or deviations of the authors of the works that make my life better? Who says better, says more fun, more challenging, more contemplative, more interesting - whatever: they make my life different, they add dimensions to it, be they philosophical or in the realm of the most basic entertainment, it doesn't matter. (Or it shouldn't matter, but maybe it matters more than we think.) Should we demand of artists and creatives that they be exemplary citizens, impolite individuals, people who cannot be faulted? Couldn't creativity also derive precisely from imbalances, flaws (sometimes character flaws), duality, conflicts - intricacies of character, and so on?

It's becoming clear that there are more questions than answers in this matter. On the one hand, if an artwork had no labels, the private life of its creator would be perfectly indifferent to anyone who appreciated the work - without references, without signatures, without a concrete and identified human being giving rise to it, they would just be works; on the other hand, we can't ignore the fact that a substantial part of the charm of any creation, especially in pop - let's call it, wholesale, all art and its cultural derivatives that make up the non-erudite universe - is directly linked to and inseparable from the profile of its creator. It is no coincidence that the success of tragic artists tends to skyrocket after their tragedy, for example; in the same way, fascination with a creator's style, way of life, or extra-artistic discourse will influence the public's perception, giving or taking away what, for lack of a better scientific definition, we call charisma. What's more, there are many cases in which an artist's bad personal reputation, even though it comes at a considerable cost to a large part of the public, ends up building loyalty among the niche target audience. There are even cases where you don't even have to be an artist to have fan clubs (take the cases of various serial killers who have become pop stars in the United States, for example; there may also be cases of psychopaths who are as bad artists as they are human beings - hello, Charles Manson? - and who don't even get rid of their legions of admirers).

There are curious phenomena in our relationship with artists and artists' art. If, in some cases, we are perfectly able to separate the waters - Picasso has not been institutionally canceled or ostracized by the majority of the public as of the end of this article - there are others in which those same waters become murky. What's more, it's not a given that each of us has the same attitude, be it complacent or accusatory, towards art and artists, no matter how much we all find ourselves in the same circumstances. Two quick, contemporary, and widely known examples: are Michael Jackson and Woody Allen. Recently, and after he died in 2009, accusations have resurfaced that the "King of Pop" abused children at his ranch in Santa Barbara, California, which he suggestively called Neverland. Michael Jackson bought Neverland in 1988 and owned it until he died, but ended up leaving the ranch in 2005, following accusations that he was a pederast, a child molester: Jackson would never return to his beloved Neverland until the end of his days. And yet, out here in the real world, his fans never stopped celebrating him, adoring him, or buying his records. Michael Jackson indeed benefited from the fact that social networks were, during the 2000s, little more than a sample of what they are today, 15 or 20 years later and 4 or 5 billion users later. But it's still strange, not to say deeply bizarre, that an adult man would make a habit of taking children to his ranch, without their relatives around and occasionally keeping one or two minors to sleep over. In his room. In his bed. On a ranch called Neverland. And no one protested - on the contrary, the parents of the boys and girls proudly and devotedly handed their children over to the man many called Wacko Jackson. If you don't know what a wacko is, just google it.

Woody Allen, on the other hand, a poor clarinetist who is also known for being a director, actor, and brilliant screenwriter - and a very interesting writer, in any case, and beyond cinema - has found himself besieged and canceled all over the place because of an accusation of sexual abuse that is so nebulous that no evidence has ever been found that he committed any kind of sexual abuse on his stepdaughter Dylan Farrow. In fact, the plot of this wild story, which includes marriage to Soon-Yi Previn - Mia Farrow and André Previn's adopted daughter who met Allen when he was married to Farrow (yes, we're still a long, long way from normality) - among other details capable of tying the most open-minded and progressive of people in knots, points much more to a kind of mad revenge by Mia and Dylan Farrow against the director of Annie Hall and Manhattan than to any crime committed by Allen. And yet, the director has been progressively sidelined by the American star system (mainly, but not only), and has lost relevance over the last two decades.

Another case that led to the artist's ostracism and, in general, cancellation, is the one centered on actor Armie Hammer. The contours of this one are even more complex than those involving Woody Allen - exchanges of messages, fetishism, ideas and suggestions of cannibalism, accusations of sexual abuse - but the outcome is similar: there are not even any legal cases against Hammer and none of the complaints resulted in any proceedings being opened against the actor. On the contrary, it eventually came to light that the woman who accused Armie Hammer of sexual abuse had stalked the actor all over the world for two years - in other words, Hammer was the victim of stalking for as long as the case was in the media spotlight, without the accusations ever resulting in a prosecution, let alone a conviction. However, in these situations, it is much more difficult to counter defamation with facts than it is to defame in the first place. Nobody cares whether or not Armie Hammer is guilty of what he's accused of in any case, he's a cannibal sex fiend who should never have starred in the movie, Call Me By Your Name (2017), in which he plays a... pederast, okay, but without cannibalism.

The list of artists with dubious conduct, regardless of the responsibility and guilt they bear concerning the fame they have been granted, could go on and on. Hasn't Kanye West, for example, who is black and African-American, become notorious for his extreme right-wing positions and his support for racial discrimination? To the point of having certain contracts and partnerships with brands, such as Adidas, canceled. Johnny Depp was the co-protagonist in a case of domestic violence, together with Amber Heard, the outlines of which are at least embarrassing and which were judged, in terms of the posture and behavior of the belligerents, to be up to the mark. And Marilyn Manson! This made-up bubblegum pop star disguised as a satanic ritual, how many complaints has he been the subject of, how many lawsuits is he involved in, or has he been involved in? The younger generations seem - at least in a light-hearted "this is what I see from here, from where I am" kind of way - more inclined to do this, they seem to demand of an artist that he be exemplary, otherwise his art ceases to have value. There will be explanations for this, and they could range from the susceptibility of the younger public - naturally and necessarily more prone to idolatry and therefore more vulnerable to the failure of their idols, which quickly turns into sentimental disillusionment - to the prevalence of what is established as truth and moral principle from the currents and trends that are boiling up on social networks. The importance that an artist has for each person, as well as the seriousness of their faults, must contribute more ingredients to the total explanation for the mixture between art and the artist, or their distinction. However, we've reached this point and we realize that we've gone round and round in circles because the initial question remains. Deservedly or undeservedly, these figures of popular culture, artists, creators, and perhaps geniuses, have the reputation of having done badly, of not having performed up to expectations - in essence, of having failed us - attached to their public images. What do we do now? Do we take their movies, their paintings, and all their records and burn them?

Translated from the original in the Arts Issue, published November 2023. Full stories and credits in the print version.

Most popular

.jpg)

Relacionados

.jpg)

Anna Wintour e o presidente da câmara de Milão, Giuseppe Sala, revelam a localização do Vogue World 2026

24 Feb 2026

O que lhe reservam os astros para a semana de 24 de fevereiro a 2 de março

24 Feb 2026