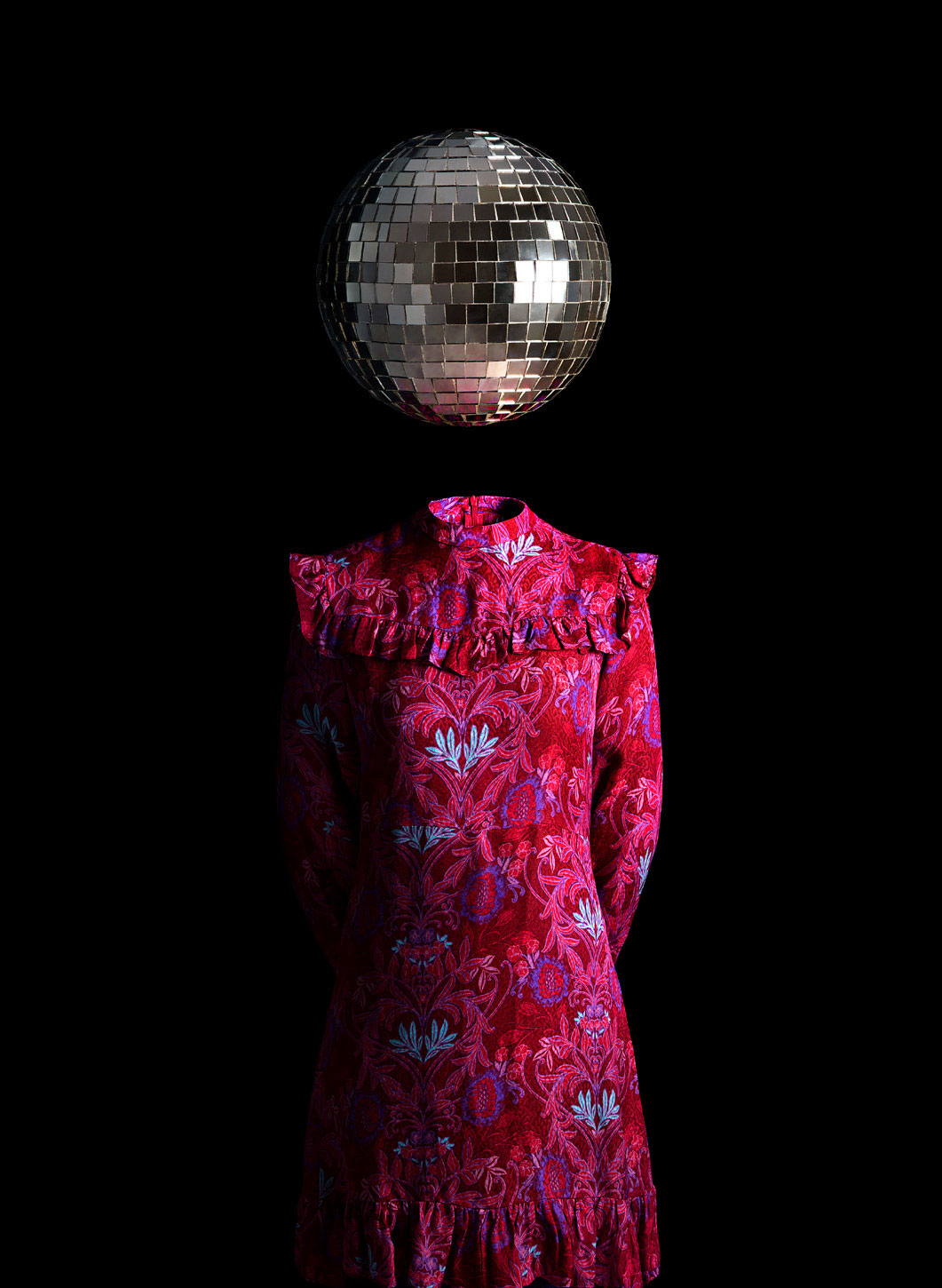

Man as a reflective object. Man as the reflected object. Man as an influence, a social and communal being, as a source and destination of all examples and practices, as a participant in a game of mirrors virtually infinite. We’re all mirroring each other. In good times and in bad times.

Man as a reflective object. Man as the reflected object. Man as an influence, a social and communal being, as a source and destination of all examples and practices, as a participant in a game of mirrors virtually infinite. We’re all mirroring each other. In good times and in bad times.

We’re living a problematic moment, “literally” defined by a scourge. Portuguese people from different ages, but with special incidence in the sub-30 category, say that anything is “literally” something else – when on only very rare occasions are they in presence of something that is literally what they were referring to. On the contrary, when “literally” is used this lightly, empirical experience tells us that, in fact, the correct adverb to be employed should be the opposite, which means, figuratively. This trend consisting of saying that something is “literally” something else has been imported from the United States of America, a peculiar country where people emphasize the most common of trivialities with a big, fat “literally”. The misplaced “literally” trend has reached such proportions that the very popular TV show How I Met Your Mother ended up dedicating an entire episode to it (spoiler alert, episode 8, season 3). We’re literally, figuratively speaking, in front of a typical case of behavioral virality, a phenomenon that explains a portion of the movements and actions of the masses. The analogy between massified behaviors and the propagation of viruses – from where the word “virality” comes from – is interesting and imaginative, despite the fact that, nowadays, it sounds like a distasteful joke. It’s curious to think that the all-knowing, independent, individual, free, and progressist human being is after all capable, under certain circumstances, of behaving much like a virus – this is an analogy and shouldn’t, therefore, be taken in a verbatim sense, therefore, not literally – replicating gestures (or, in the case of “literally”, the expressions) of one another, originating a tendency. In the end, human beings, when it comes to behaviors, preferences, or trends, contaminate each other – yes, literally, and this time we have science on our side to justify the terminology, but we’ll get there, one step at the time.

Mirroring Mirrors

We’re each other’s mirrors. What we do influences our surroundings, the same way we are also influenced by what other people do. This might sound like a La Palisse affirmation, but it’s more complex than what it might seem. It is also way more interesting. People who use the term “literally” left and right aren’t the only ones who participate in this reflection game of reciprocal influences. We’ve all played a part, consciously or not, in this exercise of mirroring others, whether in the smallest of details or big gestures, in small wants or big ambitions, originating the aforementioned trends, currents, fashions. Let’s consider some concrete examples, such as traveling by plane – a greatly missed activity for those among us that did generously often before the newly-arrived coronavirus decided to show the world why the term “viral” is employed as a synonym for something that spreads quickly and easily. The implementation and growth of low-cost air-companies allowed flying to become an accessible option for many. Numbers show that, between 2009 and 2019, the number of flights has grown consistently year after year: from nearly 26 million flights around the globe to 38,9 million in 2019 – and there was a pre-COVID 19 estimate of 40,3 million for 2020. It so happens that these numbers didn’t grow due to a sudden rise in the need for traveling a little all over the world; in fact, it was actually due to a trend in consumption that massified and got bigger and bigger. The same thing happens, for example, with smartphones, whose global sales figures went from 120 million in 2007 to nearly 1600 million in 2020. Likewise, this wasn’t a growth directly dependent on a need, but on the diffusion of a trend instead – one doesn’t need much time to realize that new smartphones sell like hot cakes the minute they hit the market. And why? Because we want what everybody else has. We don’t want literally everything nor from everyone, of course, but we reflect what trends dictate, ending up contributing to their growth in the process. The effects of how we actually reflect each other are numerous, and it would be a mistake to think they’re all bad – they might be, but not necessarily. Take a look at the trend, for instance, to moderate the consumption of meat, referencing the number of people who converted to veganism: in the United Kingdom alone, a case we more easily can identify with, the number of vegans as quadrupled from 2014 to 2019. We are not far from reality if we counterpose these numbers to the trend’s growth in Western and Central Europe. Environmental concerns such as the one leading to the exponential rise of adherents to veganism are, in fact, some of the tendencies people have adhered more to thanks to this kind of reflection on the matter. These movements are related to a form of group moralization. Truth is, people’s consciousness is affected, for the most part, by the influence other’s examples have over them. Suddenly, a matter that was seemingly distant from us became a responsibility because somewhere, someone turned it into good practice and we observed – and thus changed our posture and behavior, moving closer to the example we’ve been given.

Braincells and Behaviors

Science explains it. Because science discovered we have mirror brain cells. Science, nowadays, discovers pretty much everything about anything, even about the most unusual of subjects. In this case, it discovered mirror brain cells. I believe that if it continues to dig, it’ll find even more surprising artifacts inside our heads. On one hand, it’s great, because it can help solve problems and treat diseases. On the other hand, it takes away a little bit of fun out of life, since the mystery is a substantial part of its charm. What will remain for us to glimpse at when everything is deciphered, and there’s a solution for everything? Moving on. There is indeed a scientific explanation for the fact that we all mirror each other, what justifies the millions of gestures, actions, behaviors, and even thoughts, from daily life’s waste to massive consumption, from social media to travel trends, from habits and traditions around us to our own toxic virality – the propagation of prejudices, or the perpetuating of retrograde customs. Let’s get back to the mirror brain cells. This type of cell was firstly observed in monkeys, which adds a charming flair of scientific validation to the adagio monkey see, monkey do. More recently it was discovered that we, relatively close relatives to monkeys, are also equipped with these mirror brain cells. Their function is, in lay terms, to replicate the action of other brain cells on the moment we’re executing an action. Meaning, they copy each other whenever we execute a certain task. What’s surprising is the fact that these cells are also instigated, though less intensively so, by outside stimuli. The activity of mirror brain cells is fundamental, for instance, in order to generate empathy. Men and women present distinct levels in this kind of neuro activity, as women surpass men, thus indicating a larger female over male disposition in order to feel empathy. A deficit of these brain cells was detected in people with disorders in the realm of autism, who normally show signs of struggle in understanding the minds of others. Specialists believe that this mirror neuroactivity plays a role when it comes to social understanding. This means, we need these cells in order to have a more accurate perception of the environment we’re inserted in and the people surrounding us. Therefore, certain people’s coldness might be scientifically explained, as not all of them suffer from deliberate grumpiness.

The secret behind a yawn

Yes, if someone yawns close to us it’s likely we’ll yawn right back at them. On that note, there doesn’t seem to be any romanticism about this, but this is a phenomenon – the return action – that can happen just as easily with smiling, what, let’s admit, takes thing to a whole other level – and it’s not just about being nice, but empathic. And what we can blame this on is, as it is for sure easily to anticipate, the mirror brain cells. They’re the ones that lead us to automatically react to exterior impulses. They’re the ones that make us, according to the neuroscientist Vittorio Gallese, “programed to see other people as similar to us, much more often than as distinct – in the end, as humans we understand that the person in front of us is our equal.” But what happens when the person in front of us is ourselves? Let us put aside the mirror brain cells’ automatisms and focus on our own image: just us and our reflection. Do we yawn or smile back at ourselves? With no one left to imitate, what do we reflect? We’re in a highly intimate situation whenever we look ourselves in the eye. It can even become disturbing. There are numerous experiences focused on the behavior of individuals when faced with their own reflection and the conclusions almost always point in the same direction: in front of a mirror, our self-consciousness is magnified. At first, a long stare in the mirror, a lengthy examination of ourselves will result in a deeper evaluation of what we are and expect of ourselves. Meaning, since we have no one to imitate, we become more demanding. On a moral scale, this exercise tends to produce very positive results, since it demands contemplation and introspection. Altruistic notions, such as the search for the common welfare, might be sublimated whenever facing one’s own reflection. However, this demanding posture we assume with ourselves may come with a negative side – and doesn’t that side reflect, excuse the expression, on our daily lifestyle? Who knows if we might not become more competitive and ambitious, thirsty for the so-called success, because every morning (and several times a day) we look at ourselves in the mirror? “Who are you, man, what have you done with your life?”, and in a mere second, our brain kickstarts, adrenaline skyrockets, and there we go straight to infinity, breaking through the cosmos only so that the next day we can stare at the mirror and say: “I did that and I am this” (and what if it isn’t enough?). What if we didn’t look in the mirror? What if we had no reference and mirrored literally no one? Would we be more barbarous than we already are?

Translated from the original on Vogue Portugal's The Mirror issue, published january 2021.

Most popular

Editorial | The Naif Issue, fevereiro 2026

03 Feb 2026

Relacionados

.jpg)