For a long time, it was rebellious and badly behaved, but in recent years, by force of circumstance, it has been forced to keep a low profile: cancellation culture oblige. Famous for inciting revolutions and inspiring change, fashion is now more restrained, more timid, more moderate. Has it lost its ability to shock us?

For a long time, it was rebellious and badly behaved, but in recent years, by force of circumstance, it has been forced to keep a low profile: cancellation culture oblige. Famous for inciting revolutions and inspiring change, fashion is now more restrained, more timid, more moderate. Has it lost its ability to shock us?

“A naked model in a dress [made] of razor blades provided a shocking end to London Fashion Week.” This was the beginning of a BBC News piece from September 30, 1998, regarding the presentation of Andrew Groves’ spring/summer 1999 collection. “Designer Andrew Groves thrilled audiences with his show, entitled Cocaine Nights. His inspiration came from the hit and blockbuster thriller Face/Off, the tale of a crook who steals the face of an FBI agent. In keeping with the storyline, his models appeared with flesh-colored masks glued to their faces, which covered their eyes and mouths, as they paraded down the runway dressed in all-white garments.” What didn't the official UK media review say? That the runway was covered in a white powder (an absolutely literal allusion to cocaine, if there were any doubts), that the models looked fragile, unhealthy, almost washed-out, in line with the trend of the time, the dreaded and controversial heroin chic, and that the show's title, Cocaine Nights, could also be a reference to J. G. Ballard's homonymous book, released two years before. It is said that the rebelliousness of Groves - one of the most respected and talented designers of his generation, a collaborator of Alexander McQueen and now a professor at the University of Westminster - was seen as a response to criticism by then US President Bill Clinton that the fashion industry was allegedly glamorizing drug use. Despite his extensive (and successful) career, it is still that moment that sets him apart from all his peers. How to compete with one of the most unexpected (and, if you like, provocative) fashion shows ever?

Apparently, with some restraint. In the last two decades, fashion - which has always liked to transgress the conventions, the greatest proof of freedom and, perhaps, of creativity - has become more restrained and less rebellious. The madness of other times, when anything seemed possible, has turned into a controlled apathy, interrupted here and there by a more non-conformist designer whose life does not depend on the income he or she can (or cannot) get from his or her creations. The industry has become so large that it is difficult to make “anything” that is particularly original and shocking. It is a matter of size, yes, and money. For an industry so dependent on capitalism, it is no longer possible to produce (collections, campaigns, images) without considering the impact those might have, both on the regular customers and the final accounts for the year - not to mention the widespread fear of alienating potential buyers. Moreover, today it is impossible to be disruptive without being aware that this can cause more problems than a headache because of a bad headline in a newspaper, as it did two decades ago. These days, any content that “doesn't appeal” to the public - and here we make a parenthesis because it is indeed very complicated to understand what does or doesn't appeal, to whom, and under what circumstances - is annihilated and persecuted until its author is “cancelled.” Until the social media boom, fashion lived well with provocation and shock. Is it an exaggeration to say that it fed on them to evolve? We don't think so.

After the emergence of apps like Instagram, where everything is shared and scrutinized, images that until then were received “in silence” are now commented, dissected, analyzed, filtered - murdered. From the recent controversy with Balenciaga's late 2022 campaigns to the backlash suffered by Prada in 2018 over some dolls from the Pradamalia line that allegedly resembled blackface, the industry has had its hands full with (official) apologies to an audience that is attentive and alert. On the other hand, it is an all too obvious fact that we are bombarded with a gigantic number of images these days, coming at us from everywhere, all the time, constantly. This was not the case when Andrew Groves presented Cocaine Nights, and that makes it even more special. Nothing impacts us anymore, nothing captivates us anymore, nothing surprises us anymore. Our attention is asleep, and jumps from post to post like a ladybug in the sun: we don't know what we want to see, but we know we want to see something else; we need something else, something new, but not even “the new”, once it arrives, satisfies us. And if finally, by luck or by force of algorithm, we find something “different”, the system in which we are inserted ends up, in a certain way, annihilating it. That's exactly what happened last October, in Paris, during the presentation of Coperni's spring/summer collection: Bella Hadid appeared on the catwalk in lingerie and stilettos and, suddenly, the dress she wore on the catwalk was painted there, in loco, by two men carrying two spray cans. The moment became SO viral that, less than twenty-four hours later, some people were saying they were sick of watching the video, shared to exhaustion by internet users, who were ecstatic about “the novelty.” After that, one already knows: the memes start, and what at first was just a wonderful fashion moment, one of the most original we've seen, also became a joke.

Are we doomed to drink from our own fatigue, until one day all the smartphones and computers in the world are switched off, so that then, again virgins of this cacophony of information, we can finally appreciate what is presented to us? Or is it that fashion is no longer able to provoke us? None of the above. If there is one industry that has always managed to navigate its relationship with the powers that be, it is fashion. Since its beginnings, we associate it with rebellious and disruptive acts, whether in the form of revolutionary personalities, who marked an era, or in the launch of avant-garde trends, which ended up changing the way of thinking (and dressing) of an entire society; it was fashion, and only fashion, that realized that it was impossible to respond to the need for novelty (demanded by capitalism) without some transgression and irreverence. Intentionally or not, this is how icons were born, such as the miniskirt, one of the most revolutionary garments of all time, and of which we tell the story on the first pages of this issue. The audacity of Mary Quant, the great promoter of the miniskirt, was both celebrated and criticized, to the point that that half meter of fabric was banned in some countries, such was the shock. Similarly, photographers like Guy Bourdain, Helmut Newton or Chris von Wangenheim, authors of hypersexualized images, caused a real earthquake among magazine consumers, who were not used to the strongly erotic subtext of the photos they published in titles like Vogue Paris or Harper's Bazaar - even today, many of those pictures, true works of art, are viewed with suspicion by those who cannot understand the need to mix clothing and naked sensuality.

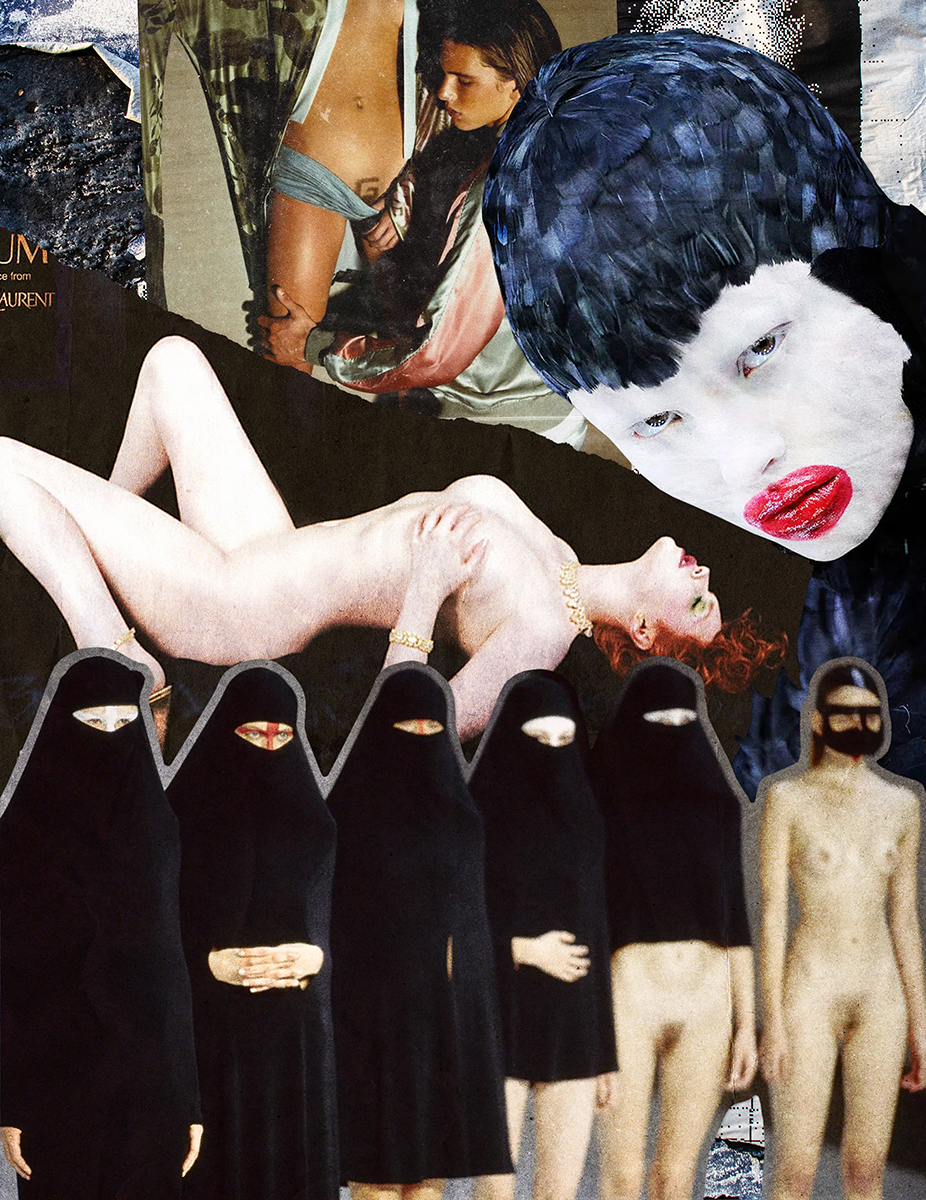

This is precisely why campaigns like Gucci’s and Yves Saint Laurent’s (among many others) were simultaneously applauded and “cancelled” even before the word existed: in the case of the Italian brand, we are talking about the symbol of an era - the Tom Ford era. The image in question, photographed by Mario Testino, ran the world, and became an icon for all those who understand fashion as something more than a trend-setting machine. But not everyone saw it that way, because in 2003 seeing a half-naked, open-legged model with a “G” shaved in her crotch, while a man languidly kneels in front of her, was too much - in 2023, let's face it, it would be impossible. Yves Saint Laurent did it twice, both times because of perfumes: the first time in 1971, when the designer himself was photographed, totally naked, for the launch of Pour Homme; the second time in 2000, when a voluptuous Sophie Dahl appears as she came into the world, in the ad for Opium - photographed by Steven Meisel and orchestrated by Tom Ford, who has never shied away from controversial images, it was the eighth advertisement that received the most complaints in the UK. We would need a single issue to remember “the old days” when wit and art joined to communicate, in an exquisite way, “what's fashionable”, while passing subliminal messages about the world - just look at the successive Benetton campaigns, a scandal for the prudes of the 21st century, which were nothing more than a way to launch the debate about relevant issues. Who in their right mind would approve of them today? No one. Just as hardly anyone would give the green light for Hussein Chalayan to carry out his Burka show, in 1996, in which the models appeared with burkas of different sizes - which got smaller and smaller as the show progressed, until there was nothing left of the fabric, and they were completely naked. This “provocation”, which aimed to question the link between the uniform and the identity of the individual, but also freedom, femininity and modesty itself, is still seen today as one of the best and most radical analyses made by a fashion designer, and cemented the idea that Chalayan was indeed a unique and original designer.

In the same way, geniuses like John Galliano or Alexander McQueen, who produced the most impressive fashion shows of the beginning of the century, would have some difficulty replicating their extravagant ideas in the present - the former knows it well, so much so that he has maintained an ultra low profile posture since the scandal that led to his departure from Dior and, subsequently, his entry into Margiela. McQueen, who disappeared in 2010, was an enfant terrible in a pure state, his natural condition was to shock. Almost all his shows were requiems for fashion fanatics, from Highland Rape (1995) to Horn of Plenty (2009), not forgetting the fantastic No13 (1999) and Voss (2001). Throughout his 18-year career, McQueen disrupted the industry with his subversive collections, which blurred the line between the realm of fashion and the art world. A natural born provocateur, it was this drive, this need to break boundaries, that became his trademark, changing the course of fashion history forever and ever - and inspiring others to follow his path. And now, where do we stand?

In a limbo. In 2011, Kate Moss walked for Louis Vuitton. So far, so good. But she did it on National No-Smoking Day, and her appearance included a cigarette, which she smoked proudly, to the horror of many mothers and fathers who were already afraid of the affection their children felt for Miss Moss. A fait-divers that served to increase (even more) LVMH’s sales. Years later, in 2015, Rick Owens decided to send some “human backpacks” to the runway - according to the designer, the collection was about nutrition, sisterhood/motherhood and regeneration, along with women who raise women, women who become women and women who support women -, and the following year some models chosen to present Season 4 of Yeezy, Kanye West's brand, collapsed due to the excessive heat in New York - here's something shocking, and not for the best reasons. The launch of a rocket, for Chanel's fall/winter 2017, was dramatic, like almost all the shows engineered by Karl Lagerfeld, as well as Balenciaga's fall/winter 2022 presentation, one of the most powerful of the last seasons, which took place a few days after the start of the war in Ukraine: we could see men and women struggling against the snow and wind, carrying everything they had left in gigantic bags; meanwhile, the creative director of the maison recited a poem in Ukrainian. Is it possible to boil down the 21st century to so few disjunctive moments? Perhaps not. There will certainly be more actions that escape us, others of which we are not aware of - or which we do not understand as provocative. The green Teletubbie, which in 2017 appeared in Bobby Abley's show at London Fashion Week, is recurrently seen as something shocking and out of the box. In our understanding, shocking and out of the box are Demna's recent statements to Vogue in the wake of the Balenciaga scandals: “I will have a more mature and serious approach to everything I release as an idea or an image. I have decided to go back to my roots in fashion as well as to the roots of Balenciaga, which is making quality clothes — not making image or buzz. […] The show will become more about showing the collection than creating a moment. I’ve realized that that can take a lot of attention away from my actual work, which is making clothes. I want to make sure that’s what people are looking at, because I think my value as a creative is designing the product and not being a showman.” There is nothing more shocking and out of the box than this.

Originally translated from The Revolution Issue, published April 2023.Full stories and credits on the print issue.

Most popular

Relacionados