It's called binge eating and it's the eating disorder that affects the largest number of people — in Portugal and around the world. Its consequences can be devastating, especially for mental health, but it continues to be ignored by both the public and much of the scientific community.

It's called binge eating and it's the eating disorder that affects the largest number of people — in Portugal and around the world. Its consequences can be devastating, especially for mental health, but it continues to be ignored by both the public and much of the scientific community.

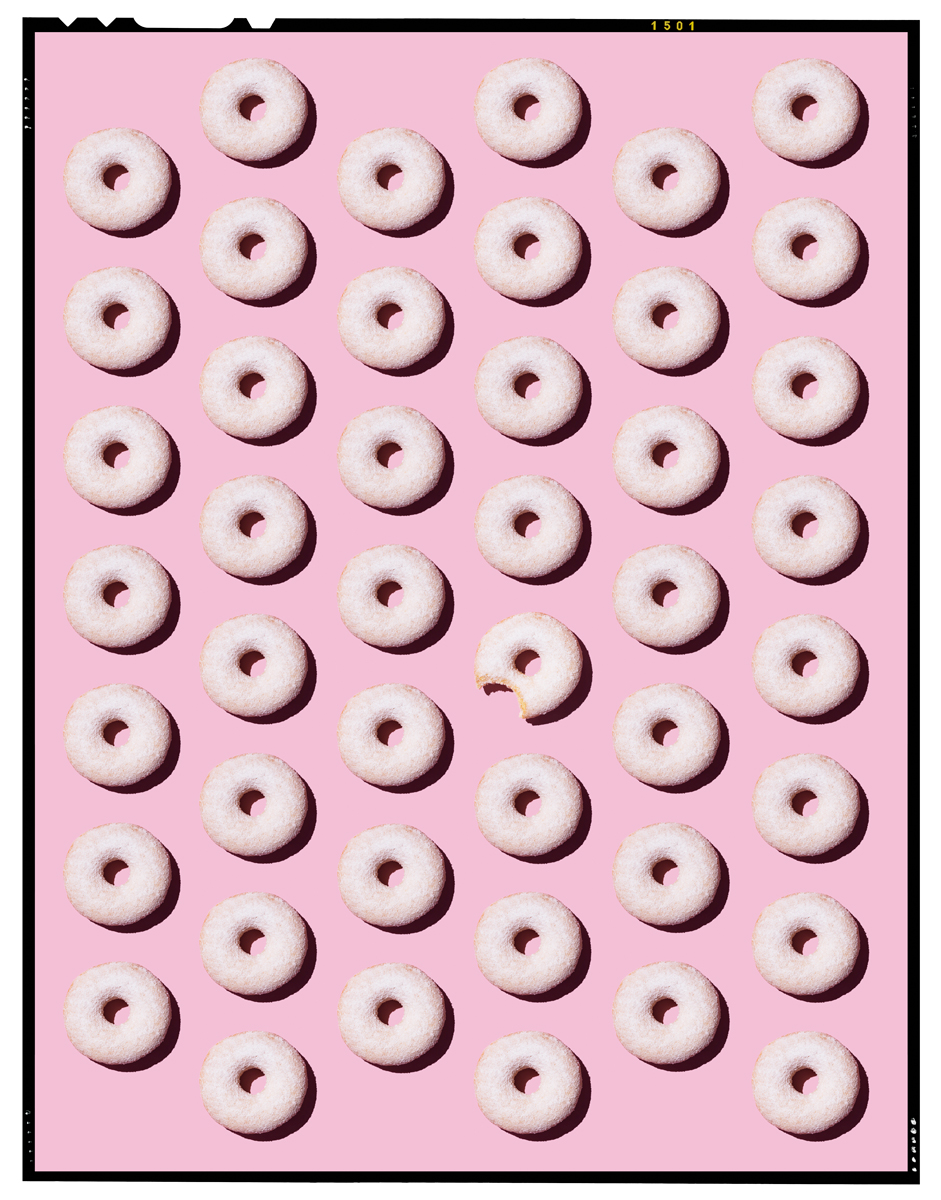

Artwork by João Oliveira © Getty Images

Artwork by João Oliveira © Getty Images

“Dear Deanne, I hope this email finds you well. In case it doesn't get lost in your inbox, of course. My name is Ana, I'm 37 years old, and I'm a journalist. I live in Lisbon, Portugal.” That’s how my message to Deanne Jade, founder of the National Centre for Eating Disorders, an organization based in Surrey, UK, which helps people with eating disorders. My investigations (the perks of being a journalist) had led me to the English psychologist, one of the most experienced in this field. I decided to take a risk, even though I knew the chances of an answer were slim. How would such a sought-after person answer me? I continued. “I have an eating disorder,” I typed, my hands shaking, guilt spilling over onto the keyboard. “I have an eating disorder. Everything I've read, every doctor I've talked to, everything points to it being bing eating. I have been dealing with it all my adult life. I know exactly when it started. I was 19 years old, had recently been living on my own and had finally plucked up the courage to end an abusive relationship that had me living under a cloud of fear and stress. As soon as I closed that chapter of my love life, I started to eat. A lot. Anytime, anywhere, for any reason. I am naturally thin, I have always had a carefree view of food (or had, until then), so when I suddenly started waling around with a pack of cookies, it didn't even occur to me that I might have a problem. My eating habits were never recommendable, that's for sure. I went from being the grumpy kid who refused to eat peaches to the brat who strolled around my grandmother's yard with a crusty cob in her hand while warning 'Nobody touches my bread!' and then to the teenager who devoured XL portions of french fries and asked for another burger when everyone at the table was full. It wasn't healthy, admittedly, perhaps it wasn't doable in the long run, that's a fact, but it was 'natural' — I didn't think about food and food certainly didn't think about me; we had a cordial, polite, no-fault relationship. Until we didn’t. From one moment to the next, as if pouring out the anguish and anxiety I had been able to contain for years, food became my refuge. Mid-morning, after lunch, before dinner, at dawn. I realized something wasn't right when people started noticing that my normally slender face looked like ‘a Rich Tea biscuit' or 'a full moon.' But I rarely weighed myself, I didn't know what calorie counting was, I thought it was ridiculous to diet, so my reaction was to accept a possible body change, normal for my age. Except none of that was normal. 'Why are you always eating something?' It was this question, thrown without malice by a friend, that shook me.”

According to information available on the website of Psinove, a psychotherapy company that gathers specialists from Faculdade de Psicologia da Universidade de Lisboa and ISPA - Instituto Universitário de Ciências Psicológicas, Sociais e da Vida, binge eating “is the eating disorder with the highest prevalence in the general population. This eating disorder is characterized by episodes of ingestion of a quantity of food that is definitely greater than most people would eat, in the same period of time and under the same conditions.” In addition, one can read, there is a manifest “sense of lack of control” throughout the episodes, which “tend to be triggered by mood swings, emotional tensions, relational or day-to-day problems, and which have the function of emotional stabilization.” However, and this is one of the most important details to point out, “unlike bulimia nervosa, people with this disorder do not use methods of compensation (vomiting, abuse of laxatives or diuretics, enemas, fasting or excessive exercise) or exhibit strict dietary rules. After these episodes (which occur on average at least once a week for 3 months), there is a tendency for feelings of guilt, ineffectiveness, disgust and worries about the effects of eating on weight and body image to set in.” Psinove’s page also mentions another characteristic of binge eating: “eating faster than normal, unaccompanied by the physical sensation of hunger, alone (away from family or friends) until you feel uncomfortably full.” The consequences are devastating, both physically and emotionally. And mentally. More than the extra pounds, visible to the naked eye, it’s the high cholesterol, the possible breathing and kidney problems, the irregular menstruation, the high blood pressure, the anxiety, the depression, the despair. Although they share some characteristics, compulsive eating and bulimia are not the same thing — even if some doctors insist on perceiving them as such and ignoring, not only the extensive literature that exists since 1992, when a study presented at the Society of Behavioral Medicine defined binge eating as an eating disorder, but also the patients who are ignored because their diagnosis is not “easy to treat.”

It was 4:06 in the morning when I finally sent Deanne the email. I didn't want to forget anything. Sometimes writing into the void is more comforting than talking to someone. Not knowing if there would effectively be a helping hand on the other end, I got it off my chest. “I was seven pounds heavier. I looked different, I felt different, my clothes didn't fit me. I started to get angry, frustrated, impatient. And to compensate for all that, I ate. At this distance, it is as if I was constantly going up and down a roller coaster with my eyes closed and my ears covered — at that time I was far from imagining that I might have an eating disorder, because apart from my 'compulsion' there was no resemblance to any of the diseases usually discussed, anorexia and bulimia. For me it was simple: I just couldn't stop eating. It went like this for a few months, until eventually my life changed and I was back to my old self. For a short while. It's ridiculous to write this, but it's the truth: I became afraid of food. It probably took me too long to accept that I needed help. The first time I went to the doctor I was almost 24. I took some medication, started therapy, felt better. I was in charge again. 'I can do this by myself', I thought. 'I don't need pills for anything', I repeated in front of the mirror. I stopped the medication. I dropped therapy. Mistake. It all came back even stronger. If people could see what I ate, they'd be disgusted. I would be disgusted if if I saw myself eating so many things so fast. And without even savoring them… It went like this until I turned 34. I would go to the doctor, start medication, feel better, and inevitably decide that I should (that I 'had to') do everything myself. Sometimes I would stop the medication for a year. Other times I would agree to take it for 12, 14 months. The 'compulsion' never totally disappeared, but it was never constant either. It would have been impossible.” I wonder what someone thinks when reading something like this, that I'm crazy? Every time I tried to share “this” with someone the answer was heartbreaking: “Hey, Ana, we all have days when we eat a little bit more. Who hasn't sat on the couch and devoured a bag of popcorn?” And I would smile. Because the box of popcorn was "for kids." On a good day, I would be able to eat a bag of popcorn, yes. And a pizza. And an ice cream. And four boxes of chocolate. On a bad day, it would be twelve loaves of bread, twelve croissants, thirty-six Kinder chocolate bars, two packs of cookies….

Back to that night: “The only time in my adult life that I didn't eat compulsively was between 2017 to 2019. Not a single time. I thought I was cured. I worked as a freelancer and spent most of my time at home. The 'danger' was everywhere. How was it possible to be at home 24/7 and be able to control myself? Better, how was it possible that I didn't even think that I needed to control myself? The truth is that somehow the compulsion stopped. I didn't think about it, didn't feel the need to eat wildly or run out to buy food. By the time I realized I wasn't having a ‘binge crisis' it was six months since the last time. My life was much better. I was happy and proud of myself. I was doing well. I was 'a normal person' — a feeling that constantly runs through my head. As food is something I will always need, and is not, in itself, a bad thing (like, for example, alcohol), it makes me angry at myself for having this problem. It makes me sad that I can't just get rid of it.” At the time I contacted Deanne Jade I was devastated, of course. I felt miserable, tired, ridiculous. I couldn't deal with the fact that I wasn’t “winning” that battle. There was a voice in my head that constantly whispered, “So many people in the world are starving and you are wasting food.” Even though I knew I probably wouldn't get any answers, I finished that long vent. “I guess my hope, with this email, is that you can tell me how to get out of this. A few years ago, on the advice of a psychologist, I went to see a nutritionist and she was so radical that, apart from the fact that I never went back to see her again, I got the feeling that hardly anyone understands what I'm feeling. She told me 'From this day on you will never eat another cookie in your life.' I believe that for many people this is still a difficult problem to understand, a myth has been created that an eating disorder means not eating or vomiting, but it's not like that. We feel terrible. Is it possible to beat this?” Four hours later, Deanne answered me.

Translated form the original on The Body Issue, from Vogue Portugal, published March 2022.Full stories and credits on the print issue.

Most popular

.jpg)

Relacionados

.jpg)

Anna Wintour e o presidente da câmara de Milão, Giuseppe Sala, revelam a localização do Vogue World 2026

24 Feb 2026

O que lhe reservam os astros para a semana de 24 de fevereiro a 2 de março

24 Feb 2026